Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

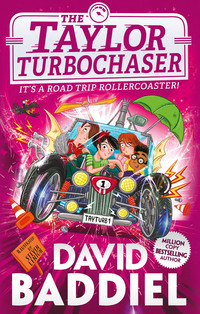

Kitabı oxu: «The Taylor TurboChaser»

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Text copyright © David Baddiel 2019

Cover and interior illustrations copyright © Steven Lenton 2019

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

David Baddiel and Steven Lenton assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of the work respectively.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008334154

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008334185

Version: 2019-09-26

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Bit Before the Beginning

Chapter 1: This story begins

Chapter 2: Not a car

Chapter 3: The Whiter-Tooth-Whiz 503

Chapter 4: “Fun”!

Chapter 5: NEEEEEWOOOOOWWWW

Chapter 6: Easier than the Hulk

Chapter 7: Better than ALL my other inventions

Chapter 8: Upside-down fish tanks

Chapter 9: Do you want to go faster?

Chapter 10: Who taught you to do that?

Chapter 11: A dip in her stomach

Chapter 12: Dank meme

Chapter 13: Click!

Chapter 14: Quite a pill

Chapter 15: The photo

Chapter 16: Let me get this straight

Chapter 17: Oh. My. Days.

Chapter 18: So jokes

Chapter 19: Like someone torturing a hundred bats

Chapter 20: Trowch i’r chwith

Chapter 21: That’s nice

Chapter 22: Something you might see in a cartoon

Chapter 23: Road closed

Chapter 24: APB

Chapter 25: Like the cheese in a sandwich

Chapter 26: Strange-looking cow

Chapter 27: Not right at all

Chapter 28: Peter Pat

Chapter 29: Good meme

Chapter 30: SAVE ME!

Chapter 31: I’m not an idiot

Chapter 32: Waving goodbye

Chapter 33: Via Big Fart Moor

Chapter 34: I can feel it in my water

Chapter 35: Don’t get cross

Chapter 36: A secret plan

Chapter 37: As Simon Cowell says

Chapter 38: Chill out, sis

Chapter 39: Definitely sarcastically

Chapter 40: HOT ROD

Chapter 41: Like when you run at some sheep

Chapter 42: Calm as a cucumber

Chapter 43: The Eagle and the Squirrel

Chapter 44: Please, no

Chapter 45: Sorry, Mum!

Chapter 46: Does it still work if it gets wet?

Chapter 47: Exactly the opposite

Chapter 48: A nice-looking restaurant

Chapter 49: Mobilcon XR-207. Located

Chapter 50: The sort of thing they say in old films

Chapter 51: If possible, make a U-turn

Chapter 52: One hundred and ninety-two and a half miles

Chapter 53: And I’ll take the low road

Chapter 54: Not very nice

Chapter 55: Believe

Chapter 56: The ready, steady

Chapter 57: Sort of like a friend

Chapter 58: Like a proper big brother

Chapter 59: A strange decision

Chapter 60: Sitting wide

Chapter 61: Baked-bean-flavour crisps

Chapter 62: Until she absolutely has to

Chapter 63: A chance

Chapter 64: Ole’!

Chapter 65: WHAT’S HAPPENING?

Chapter 66: Always fine

Chapter 67: A dodgem car by the sea

Chapter 68: “Was that sarcastic?”

Chapter 69: You can’t say no

Chapter 70: I’ve got this

Chapter 71: The biggest present ever

Chapter 72: Where would you like to go today?

Thanks to

Keep Reading …

Books by David Baddiel

About the Publisher

Amy Taylor loved cars. Here are her favourite ones:

1. The Aston Martin DB5. This is the one James Bond drives. Amy just loved the look of this one. Although as with all old cars (classic cars, as people in the know – like Amy – call them) if she had one she would get someone to remake it with an electric engine, so that it wasn’t bad for the planet. Maybe with the help of her friend Rahul, who was an inventor. Of sorts.

2. The Mercedes 300 SL Gullwing. This was another classic car. But it had doors that instead of opening normally came up like wings, making the whole car look like it could fly. It couldn’t.

3. The Jaguar E-Type, which was also an old car, but she liked the new one, called the Zero, which was actually electric. It was just as beautiful as the old car, and Amy thought it was very clever that the car had always been called the E-Type, even before there was an electric version.

4. The Ford Transit Van. Well, a Ford Transit van. Her mum’s white battered seven-year-old one.

Amy’s love for cars might seem unusual. Not because she was a girl – lots of girls like cars and lots of boys don’t – but because she had been in a really bad car accident when she was eight years old. Which also meant that since then – she was now eleven – she had needed to use a wheelchair.

Amy’s accident was also why the Ford Transit van was on her list of favourite cars. As a petrolhead – that’s slang for car fan – she knew it wasn’t up there with the Aston Martin and the Gullwing, but she also knew that her mum had spent a lot of time and money converting this old a-bit-like-Mater-from-Cars wagon into something that could transport Amy and her chair (and her very, very teenage-boy brother Jack – you’ll meet him in a bit). This made the van one of a million reasons why Amy loved her mum. She often felt an especially huge love for her mum as she easily wheeled her chair up the ramp that came out of the back of the van.

“Thanks, Mum!” she’d say, as she rolled up into the back of the Transit. “Look! I can do it one-handed …!”

Actually that isn’t true.

Or rather: it isn’t true any longer.

Amy used to be able to wheel her way easily up the ramp into the van, but not any more. The problem wasn’t with her, or the van: it was with her wheelchair. For some time now, the right wheel had not pointed in the same direction as the left wheel. Which meant that Amy sometimes felt like she was trying to get around in a supermarket trolley. And not just any trolley: one that’s been separated from all the others on the edge of the supermarket car park because, as soon as any shopper sees it, they know that its wheels will stick.

I’ve maybe gone a bit far with the trolley comparison. Although it was a comparison Amy herself would use a lot while complaining to her mum about her wheelchair. She was doing exactly that when this story begins, as they drove into Lodlil, the cheaper-than-most superstore near where they lived.

“That one,” said Amy, pointing out of the window. “Mum. The rusty one. With the soggy newspaper in it. And the wonky front wheel. That’s the kind of trolley my wheelchair is like.”

“Yes,” said Suzi, carefully backing into a space between two cars, into one of which a family was loading a huge amount of shopping. This was hard to do, as the van was large and high in the back, and Amy and her chair were in the way.

More in the way than usual, in fact, as Amy was pointing, with both arms, at the rusty trolley. “Can you see it?”

“No. But I know the one you mean.”

“You do?”

“Well. I know the kind of one you mean. Because you’ve pointed one like that out every time we’ve come to the supermarket this month.”

“Because, Mum,” said Amy, “my wheels have been that wonky for a month!”

Suzi sighed, and switched the van engine off. Life is as perfect as you want it to be, she thought to herself. Amy’s mum was very keen on “inspirational quotes”: positive things people have said about life that you can find all over the internet, normally backed by an image of a sunset. She repeated these to herself in times of stress. Often, though – like now, as she watched the man from the car next to her trying again and again to slam the boot down over a stuck bag containing mainly eggs – they didn’t seem to have much effect.

Suzi got out of the driving seat, went round the back of the van, opened the back doors (on which Amy had stuck an ironic “HOT ROD” sticker that she’d got from a car magazine called Fast Wheels) and pressed a button.

The ramp folded out for Amy to wheel down. Amy turned the chair round to face her mum. But then she carried on turning it, away from her, in a circle. And then another circle. And then another (when she wanted to, Amy could turn her chair very, very fast).

“I can’t stop it, Mum!” she called out. “The wheels are doing it by themselves. Help me! Help me! Help me!”

Suzi watched her, with an eyebrow raised. She wondered about just letting her daughter get very, very dizzy and sick. But eventually, after six turns, and no sign of either the pretend screaming stopping or the circling slowing down, she said:

“All right! OK! You win, Amy! I’ll talk to your dad. We’ll get you a new chair.”

Amy stopped and smiled. She reached into her pocket and took out a piece of paper, on which was printed a picture from the internet.

“Thanks, Mum!” she said excitedly. “Here’s the one I want!”

“It’s brilliant!” said Amy, going up the ramp into the van a few days later.

“I’m glad you like it,” said Suzi.

“I love it!” said Amy.

“Great. You can write a letter to your dad, thanking him maybe.”

“I already have! I sent him an email telling him how amazing it is. Look!” Amy turned the wheelchair all the way round, inside the van, and came back down the ramp. “It’s like a dodgem car!”

She came off the ramp and turned round again, twisting the control lever on her new, black, shiny and, most importantly, motorised wheelchair.

Her mum had parked the van in their drive and opened the back doors, so that Amy could practise going up and down the ramp. Which she had been doing for a while.

Quite a long while.

“It’s like a dodgem car …” echoed Jack, Amy’s fourteen-year-old brother, who was standing – or at least slouching, his back against the door – in their front garden, pretending not to be interested.

It was one of the things he did all the time now, repeating back anything that anyone said, in a bored, taking-the-mickey voice. Amy sometimes wondered if, when he was about twelve and a half, her brother had been secretly replaced in the night by a sarcastic echo chamber.

“Well, it is, a bit,” said Amy. “Remember when Dad took me on the dodgems, Mum?”

“Of course! He took both of you in one car. You both drove it.”

“Yes, but he let me do the steering wheel by myself after a bit. And I swerved through all the other cars. We didn’t even bump once!”

“Ha. Yes, that’s right! What age were you then?”

“Seven. And then he bought us candyfloss!”

Suzi nodded, and looked down. Amy’s dad, Peter, didn’t live with them any more. He lived a long way away, in Scotland.

“He said I was a natural driver, didn’t he, Mum? ‘You’re a natural, Amy,’ he said!”

“You’re a natural, Amy …” said Jack. In his bored, taking-the-mickey voice.

“Yes. Unlike his son, who always loses to me when we play Formula One: Grand Prix!”

Jack made a rude gesture at her. “Grand Prix,” he echoed sarcastically.

“Anyway, Amy …” Suzi said, coming out of her little trance, “is that enough practice now?”

“Not quite, Mum …” Amy said, turning round again. “I do love it, but I just want to see if I can do a bit more with it … just want to see how it corners … how it steers … what’s its top speed …”

“How it corners … how it steers … what’s its top speed …”

“Jack, stop doing that,” said Suzi. “It’s tiresome.”

“Well,” said Jack, finally speaking in his own voice, which sounded to Amy, as ever, like someone who was convinced he knew everything, even though he was only actually two and half years older than her. “Come on. It’s a wheelchair. It’s not like it’s fast or anything.”

“It’s a Mobilcon XR-207,” said Amy. “It uses technology from their go-karts. It has a five-horsepower engine!”

“OK, show me top speed, then,” said Jack.

Amy pushed the lever on the right-hand arm of the chair forward. The chair went down the drive.

Not, it must be said, very fast.

“See?” said Jack. “It’s not exactly an Aston Martin DB5, is it?”

This made Amy stop. She looked down.

“I know it’s not an Aston Martin DB5,” she said quietly.

Suzi frowned. “Oh shush, Jack. If Amy wants to have fun pretending her new wheelchair is like a car, let her.”

This did the trick – it shut Jack up. But actually – even though her mum didn’t mean it to – it also made Amy feel kind of worse. It made her feel that what she had been doing with her chair in the drive was maybe just that: a babyish game of pretend.

And, at the end of the day, Jack was right: it wasn’t a car. It was just a wheelchair.

But then Amy had an idea …

“Hmm …” said Rahul. “I don’t know.”

“Come on. You know you can. If anyone can, you can.”

Rahul scratched his head, and took his glasses off. This was something he did a lot when he wanted to look closely at something. It made Amy wonder what the point exactly of him having glasses was.

“What is the point of you having glasses?” she said (because when Amy had a thought, usually she couldn’t stop herself from saying it). “When you always take them off anyway to have look at—”

“Shhh,” said Rahul. “I’m thinking.”

He bent down and stared closely at Amy’s new wheelchair. It was, Rahul thought, stylish. It was black and shiny and the wheels were silver and looked like they came from quite a cool bike.

“What’s it called?” he said. “This wheelchair?”

“The Mobilcon XR-207.”

“Mobilcon!” said Rahul. “They make the coolest stuff. I wanted one of their amazing drones for my birthday, but my parents said it was too expensive. Your chair must have cost a fortune!”

“Yeah …” said Amy. “My dad helped pay for it.”

Rahul nodded. “It’s pretty slick,” he said. “XR-207, did you say?”

“Yes,” said Amy. “But I prefer to call it …”

Amy pulled the lever on the arm of the chair backwards, and the wheelchair went back, faster than you might think.

“… The Taylor TurboChaser!”

“Hey!” said Rahul, chasing after her. They were in the playground of their school, Bracket Wood. Amy and Rahul were in Year Six. Amy was the only kid in a wheelchair at the school. The teachers sometimes tried to make her feel OK about this. Which wasn’t necessary, as she felt OK about it already.

Her form teacher, Mr Barrington, had once said to her, with an awkward smile on his face, “The way to think about being in a wheelchair, Amy, is that it makes you very special.”

And she had told him to bog off. Which she didn’t get punished for. Probably because she was in a wheelchair. So in a way, Amy thought later, he was right.

Rahul caught up with her. She pulled the lever to the right – the chair moved smoothly off in that direction. Rahul went towards her, but with a smile she jerked the lever to the left, and the chair went left, dodging him. She stopped and looked up.

“You see? The steering’s already as sharp as a Ferrari.”

“Yes, OK,” he said, breathing heavily. “But there’s a long way between that, and me making it into an actual—”

“Rahul!”

He looked over. Their friend Janet was approaching, holding something that looked like a motorcycle helmet, with a toothbrush in the middle of it. Which is exactly what it was.

It was, in fact, an old motorcycle helmet, with a little battery-powered motor at the side, attached to a small metal rod. That rod was then glued to a toothbrush, positioned round about where the mouth of the helmet-wearer would be.

“Yeah?” said Rahul.

“This new invention of yours …”

“The Whiter-Tooth-Whiz 503. Yes?”

“Is that what it’s called?” said Amy.

“Yep.”

“So are there … like … 502 other models?”

Rahul thought about this for a second. “No,” he said. “Are there 206 other versions of your wheelchair, the Mobilcon XR-207?”

“I don’t think so. Fair point.”

“Anyway,” said Janet, “it doesn’t work.”

Rahul frowned and took the Whiter-Tooth-Whiz 503 out of Janet’s hands. He pressed a switch on the motor. The rod vibrated: as did the toothbrush.

“Yes, it does work,” he said, looking up.

“No,” said Janet, who had started looking at her phone. “You said it would clean my teeth. Without me having to do anything. But that’s wrong. Because I still have to a) put toothpaste on the brush, and b) move my mouth around so that the brush gets to different teeth.”

When Janet said these two points – a) and b) – she didn’t do what people normally do. She didn’t hold up two fingers, one at a time, or point to two fingers, or anything.

She just said it. This was because Janet was one of the laziest people who ever lived, and preferred, whenever possible, not to do anything except look at her phone.

Which, in fact, was why she had been very keen on the idea of the Whiter-Tooth-Whiz 503.

“It doesn’t work!” said Janet.

“It does!” said Rahul.

“It’s meant to be an effort-saving device.”

“Yes. To save you some of the effort of cleaning your teeth. Not all of the effort!”

“I wanted to be able to clean my teeth and text at the same time!”

Rahul sighed.

“You’re just lazy,” said Janet, which was ironic.

“No, he’s not,” said Amy. “And he’s going to make this wheelchair into something incredible, aren’t you, Rahul?”

Rahul swallowed. “Well … I’ll try,” he said.

Which was good enough for Amy.

Amy was right: Rahul really was far from lazy.

The Whiter-Tooth-Whiz 503 was only the latest of his inventions. It had been commissioned by Janet. By commissioned, I mean Janet had said, one day, “I hate cleaning my teeth every night, it’s so boring,” and Rahul had said, “I’ve got an idea,” and gone off, designed and made the machine, brought it back to school, and asked Janet to pay the costs of making it – eight pounds – which, so far, Janet had not paid.

He had also invented:

The Alarm Clock-to-Dreams Device 4446. (You may have noticed by now that all Rahul’s inventions have random numbers, to make them seem more like proper inventions. This was why he was so interested in the name of Amy’s wheelchair.) The Alarm Clock-to-Dreams Device 4446 was an alarm clock fitted with a recording microphone, so that when it woke you up, before it had a chance to vanish into your head, you could shout out what happened in last-night’s dream. Rahul was working on an upgrade of this invention, whereby the words would become animated pictures, immediately uploadable to YouTube.

The Toast-Butterer 678X. (Rahul realised while designing this that to sound really like a proper invention, he needed to add letters AND numbers.) This was a knife attached to a toaster, which, when the toast popped up, would automatically start buttering it. This did require quite a powerful spring, because if the toast was only halfway out of its slot, the buttering would only butter the top half. Which was not only not as nice, it could also mean the butter would drip down into the toaster and make it explode. As a result of this happening the first time Rahul tried it, the Toast-Butterer 678X had been banned from Rahul’s parents’ kitchen.

The All-Weather Brella 778Q. On the basis that the weather in Britain is quite changeable, and opening and shutting an umbrella over and over again can cause it to break, Rahul had created an umbrella into which he had built a sun roof (a polythene window with a zip, basically).

The Snowman Life-Extender XJ59P. “Have you built a snowman that you’re really proud of? That you’ve spent ages on, and looked out of the window at after a hard and freezing morning’s building? Only for it to melt really quickly and depressingly into sludge? Well, worry no more! Because with the Snowman Life-Extender (bespoke-designed to fit your snowman, cooled to -3 degrees) you can keep your favourite snow guy alive for as long as you like (electricity bill permitting). Maybe he might even come alive and fly with you at Christmas to the North Pole! (Disclaimer: no guarantee this will happen.)” This is a direct quote from the press release that Rahul had written for the Snowman Life-Extender XJ59P. To be honest, he had written the press release for this one before creating the invention itself. But the invention, he always insisted, was on the way.

The Coffee-Cube-Maker 7777T. This was a box with a funnel at the top, into which you poured instant coffee, and which would then – at the bottom – spit out the coffee as cubes. “What’s the point of that?” said Rahul’s father, Sanjay. This was generally not a question that Sanjay asked. Sanjay was 99 per cent convinced that his son was one day going to invent something incredible, and that the whole family would be rich. Thus, he funded Rahul’s inventions, and let him plunder the family business – a big retail warehouse called Agarwal Supplies, which stocked all kinds of stuff – for raw materials. But this one seemed to test him.

“To have coffee as cubes,” said Rahul.

“Yes, I see that,” said Sanjay. “But when you put them in hot water …?”

“They dissolve.”

Sanjay frowned. “Like instant coffee always does.”

“Yes,” said Rahul. “But they’ll look cool in the tin.”

Sanjay shrugged and nodded, and put this observation down as one of the many that meant his son was a genius he would never understand.

Bean Pants. This was the only invention that Rahul had made that didn’t have a number, because Rahul felt that it went against its brand, which was – and he often said this doing an inverted commas mime – “fun”. It was pants, the lining of which he’d filled with beans. Not baked beans: whatever the beans are that are in bean bags. Which meant that, wherever you sat, you could feel like you were sitting on a bean bag.

“Fun”!There were many other inventions on Rahul’s slate, by which I mean in his head, or doodles in his rough book.

But these were the biggies. Or at least they were until Amy’s wheelchair came along.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.