Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter»

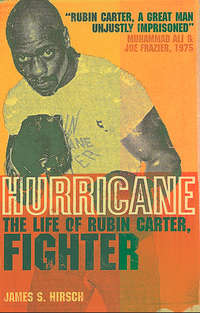

HURRICANE

The Life ofRubin Carter, Fighter

James S. Hirsch

COPYRIGHT

First published in Great Britain in 2000 by

Fourth Estate

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Copyright © by James S. Hirsch 2000

The right of James S. Hirsch to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9781841151304

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007381593

Version: 2016-03-18

HarperCollins Publishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

DEDICATION

To Sheryl,who gave me her loveand never lost the faith

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Death House Rendezvous

2. Wild West on the Passaic

3. Danger on the Streets

4. Mystery Witness

5. Force of Nature

6. Boxer Rebellion

7. Radical Chic Redux

8. Revenge of Passaic County

9. Search for the Miraculous

10. The Inner Circle of Humanity

11. Paradise Found

12. Powerful Appeals

13. Final Judgment

14. The Eagle Rises

15. Vindication

16. Tears of Renewal

Epilogue

Sources

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

1

DEATH HOUSE RENDEZVOUS

BY 1980, New Jersey’s notorious Death House had been revived as a lovers’ alcove, but Rubin “Hurricane” Carter still wanted no part of it.

The Death House was Trenton State Prison’s official name for the brick and concrete vault where condemned men lived in tiny cells and an electric chair stood hard against a nearby wall. The first inmate reached the Death House on October 29, 1907. Six weeks later he was dead, his slumped body shaved and sponged down with salt water, the better to conduct the electricity. New Jersey continued to hang capital offenders for two more years. But soon enough the electric chair, with its wooden body, leather straps, and metal-mesh helmet, which discharged three mortal blasts of up to 2,400 volts, was seen as the most felicitous form of execution.

At least one infamous death gave the site a brief aura of celebrity. Richard Bruno Hauptmann, convicted of murdering Charles Lindbergh’s baby, was electrocuted in the brightly lit chamber at 8:44 P.M. on April 3, 1936. In later years, sentences were carried out at 10 P.M., after the “general population” prisoners had been placed in total lockup. An outside power line fed the chair to ensure that a deadly jolt did not interfere with the penitentiary’s regular lighting. On occasion, “citizen witnesses” crowded into a small green room, with only a rope between them and the chair about ten feet away. The observers watched the executioner turn a large wheel right behind the seated man’s ear, thereby activating the lethal current. The body, penitent or obdurate, innocent or guilty, alive or dead, pressed against the restraints until the current was shut off.

The Death House confronted its own demise in 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty as cruel and unusual punishment. The electric chair, having singed the breath from 160 men, was suddenly obsolete. So prison officials found a new mission for the chamber: it became the Visiting Center.

Despite its macabre history, the VC was a huge hit with most of the prisoners. It marked the first time that Trenton State Prison, a maximum-security facility, had allowed contact visits. Inmates could now touch their spouses, children, or friends. The metal bars were removed from more than two dozen Death Row cells near the archaic chair, its seven electric switches still in place. The rooms were not exactly cozy hideaways, but they became the unsanctioned venue for conjugal meetings. Inmates seeking a bit of privacy tried to reserve cells farthest away from the guards, and the arrangement, as described by some old-timers, gave rise to Death House babies.

But Rubin Carter didn’t care a bit. He refused to accept virtually anything the prison offered, and that included visits inside the reincarnated Death House.

He was repulsed by the prospect of sharing an intimate moment among the souls of 160 men, some of whom he knew. Transforming this slaughterhouse into a visiting center, Carter believed, was like turning Auschwitz or Buchenwald into a summer camp for children. It was another way for the state to humiliate prisoners, to express its contempt for the new law that pulled the plug on its chair.

Carter knew well that he could have been one of the chair’s immolations. In 1967 he had been found guilty of committing a triple murder in Paterson, New Jersey. He adamantly claimed his innocence. The state sought the death penalty, but the jury returned a triple-life sentence instead. That conviction was overturned in 1976, but Carter was convicted of the same crime again later that year and given the same triple-life sentence.

By the end of 1980, Carter had gone for almost four years without a contact visit. Since his second sentencing in February of 1977, he had not seen his son or daughter, his mother, his four sisters, or his two brothers. Most of his friends were also shut out. He and his wife had divorced. He saw his lawyers in another part of the prison.

But now, on the last Sunday of the year, Carter had a visitor as the result of an unusual letter he’d received three months earlier. As a former high-profile boxer who was known around the country and even the world, he received hundreds of letters each year, but he rarely answered them. In fact, he didn’t even open them, allowing them to pile up in his cell. Carter wanted nothing to do with the outside world.

Then came a letter in September, his name and prison address printed on the envelope. Carter could never explain why he opened it except to say that the envelope had vibrations. The letter, dated September 20, 1980, was written by a black youth from the ghettos of Brooklyn who, oddly enough, was living in Toronto with a group of Canadians. The seventeen-year-old, Lesra Martin, wrote that he had read Carter’s autobiography, The Sixteenth Round, written from prison in 1974, and it helped him better understand his older brother, who had done time in upstate New York. Lesra concluded the letter:

All through your book I was wondering if it would have been easier to die or take the shit you did. But now, when I think of your book, I say if you were dead then you would not have been able to give what you did through your book. To imagine me not being able to write you this letter or thinking that they could beat you into giving up, man, that would be too much. We need more like you to set examples of what courage is all about!

Hey, Brother, I’m going to let it go. Please write back. It will mean a lot.

Your friend,

Lesra Martin

Lesra’s words, his efforts to reach out, touched Carter. He responded on October 7. The one-page typewritten note thanked Lesra for his “outpouring of hope, concern and humanness … The heartfelt messages literally jumped off the pages.”

More letters followed between Lesra, his Canadian guardians—who had essentially adopted the youth to educate him—and Carter in which they discussed politics, philosophy, Carter’s own case, and his appeal. But when Lesra asked if he could visit the prison at Christmastime—he was going to be in Brooklyn seeing his family—Carter replied noncommittally. That did not deter Lesra. The bond between the two—and, more important, between Carter and this mysterious Canadian commune that typically shunned friendships with the outside world—had been sealed.

Winter’s chill could be felt inside the Trenton State Prison on that last Sunday of December. Built in 1836 by the famed British architect John Haviland, the prison is a brooding, monolithic fortress. Haviland used trapezoidal shapes and austere giganticism to evoke a massive Egyptian temple. Scarab beetles, which symbolized the soul in ancient Egypt, were carved into the prison’s pink limestone walls. Tributaries from the Delaware River flowed in front of the prison, in faint mimicry of the Nile.

But by 1980 the waterways had long since dried up and the pink limestone had turned brown. Loops of razor-ribbon wire topped twenty-foot-high concrete walls, and stone-faced guards stood in gun towers. The prison yard, with a softball field, weight machines, and handball courts, was said to sit over a cemetery. The yard’s red dirt was so dry that it was regularly sprayed with oil, creating a viscous sheen that rubbed off on inmates in crimson splotches.

While the prison sought total control of its inmates, Carter defied the institution at every turn. He did not wear its clothes, eat in its mess hall, work its jobs, or participate in any organized activity. He refused to meet with prison psychiatrists, attend parole hearings, or carry his prison identification card. His rationale was simple: he was an innocent man; therefore, he would not be treated like a criminal. His defiance earned him several trips to a subterranean vault known as “the hole,” where inmates were held in solitary confinement. He was also once banished to a state psychiatric hospital, where the criminally insane and other incorrigibles were disciplined.

But Carter had a predatory instinct for survival, and he was eventually allowed to live quietly in his fourth-tier cell. He continued to fight for his freedom in the courts, but by now he had immersed himself in books on philosophy, history, metaphysics, and religion. Searching for meaning in his own life, he turned his cell into “an unnatural laboratory of the human spirit.” He studied, wrote, and tutored other inmates about the need to look within themselves to find answers to the world outside.

Carter had been on this personal journey for more than two years by the time a guard came to his cell and told him he had a contact visitor. Suspecting it was the letter-writing youth, Carter walked down his tier, through the center hub of the prison, and past the infirmary, which was conveniently next to the Death House. (The infirmary used to receive the electrocuted bodies.) Before entering the Death House, he gritted his teeth and disrobed for a strip search—standard procedure for every prisoner before and after a contact visit. Searching for contraband, a guard ran his hand through Carter’s hair and looked inside his mouth, under his arms, beneath his feet, and up his rectum. This degrading invasion was another reason Carter avoided contact visits.

Once inside the chamber, Carter reserved a cell on the lower tier, placing his plastic identification tag and a pack of Pall Malls on two chairs. The prison visitors soon filed in and quickly joined their friend or loved one. Finally, only two people were left—Carter and a slip of a youth. The young man was trembling.

Growing up in the slums of Brooklyn, Lesra Martin knew plenty of people who had gone to prison, but this was his first time inside a pen. The high stone walls, metal gates, and claustrophobic corridors were imposing enough, but the brusque security checks were even more unnerving. He emptied his pockets, was frisked, was scanned by a hand-held metal detector, and had his right hand stamped with invisible ink. He had brought a package of Christmas cards, socks, and a hat from his Canadian guardians but was not allowed to deliver it because all packages have to come through the mailroom, where they are opened and inspected. Lesra registered and was given a number, but as he passed through the prison in single file, he was jarred by the guards’ shrill orders.

“Get back in line!”

“Don’t speak to the person in front of you!”

“Have your ID ready!”

“Put your things in your locker!”

As Lesra stood in the waiting room, he finally heard “four-five-four-seven-two, up!”

That was Carter’s prison number. Lesra waited before a dim holding bay. As the steel doors opened and visitors began walking in, several women took deep breaths while others held hands. A guard checked the right hand of each visitor with a blue fluorescent light. After about twenty people filed in, the guard yelled, “Bay secure!” The doors shut, and there was a long moment of helplessness, of captivity. Then doors on the other side opened, and everyone moved out. The experience dazed Lesra, who had arrived wanting to cheer up a prisoner but was made to feel as if he had done something wrong himself.

Rubin Carter understood the feeling.

“You must be Lesra,” Carter said. He saw a frightened but good-looking young man about six inches shorter than he. (Carter was only five foot eight.) The prisoner’s appearance stunned the teenager. Every picture Lesra had seen of Carter showed him with a clean-shaven head, a thick goatee, and a menacing stare. Now he had a full Afro, a mustache, and a smile. The two embraced, then walked to the cell Carter had reserved. They sat facing each other and leaned forward so passing guards could not hear their conversation.

Lesra recounted his harrowing experience getting to the Visiting Center. “How do you survive in here?” he asked.

“I don’t acknowledge the existence of the prison,” Carter said. “It doesn’t exist for me.”

Lesra noticed that the guards patrolling the corridor did not walk as closely to their cell as to other cells, giving them a bit more privacy as a sign of respect. Lesra also heard inmates as well as guards refer to Rubin as “Mr. Carter.” When Lesra called him “Mr. Carter,” he laughed. “You can call me Rubin, or better yet, Rube.” As the inmate explained his refusal to participate in prison activities, Lesra remembered the words of Bob Dylan’s song “Hurricane,” which had been released in 1975 amid an outpouring of celebrity support:

But then they took him to a jailhouse

Where they tried to turn a man into a mouse.

The jailhouse, Lesra realized, had failed.

He described how he left his home in Bedford-Stuyvesant and moved to Toronto, where his new Canadian family was educating him. The arrangement puzzled Carter, and he told Lesra he need not worry about being alone. “I know they’re treating you well because of your smile, but if you’re ever not happy there, you let me know,” he said. The young man gave him the phone number to his home in Canada.

About an hour passed. As the visit was about to end, a prisoner who had a Polaroid camera approached them.

“You like me to take a picture of you and your son, Mr. Carter?”

“Absolutely!” he responded.

Lesra turned and began walking toward a wall that he believed would make a fine backdrop. Carter yanked him back.

“We don’t go that way,” he said. “That’s where the chair was.”

The electric chair had been removed a year or so earlier and was now in the Corrections Department Museum in Trenton. But the bolts were still in the ground, and the imprint of the chair was visible. The picture was taken against a different wall, with the two standing next to each other, smiles creasing their faces, Carter’s arm draped across Lesra’s shoulders.

As the two walked toward the holding bay, Lesra said, “I wish I could just walk you right on out.”

“Don’t worry,” Carter said. “I’m with you.”

This encounter marked the beginning of Carter’s reemergence from his self-imposed shell. He would always have a special bond with Lesra, but he would develop far more important ties with the Canadian commune, and its members would provide vital support on Carter’s journey through the federal courts. At the same time, the group’s strong-willed leader, Lisa Peters, and Carter would become intense but doomed soulmates in an unlikely prison love affair. But all that was in the future. After his visit to the Death House, Carter returned to his cell, lay down on his cot, and stared at the picture of Lesra and himself.

2

WILD WEST ON THE PASSAIC

AT THE TIME of Rubin Carter’s arrest in 1966, his hometown of Paterson, New Jersey, was dominated by Mayor Frank X. Graves. A smallish man with heavy jowls and thinning hair, he was one of the last of the old city bosses. He controlled every department in his bureaucracy, personally answered phone calls from irate citizens, and referred to anything in Paterson as “mine,” as in “my City Hall” or “my police force.” He had no hobbies and read few books. He did have a wife and three daughters, but Paterson was his life, and he took any infraction inside its boundaries as a personal wound. Faced with white flight and fears of rising crime rates, he launched a law-and-order crusade with a hard-edged moralism.

No one doubted his audacity. Graves had won two Purple Hearts in World War II for injuries suffered during the invasion of Italy. As mayor, he usually carried a pistol. Driving around Paterson in his black sedan, he monitored the police and fire radio scanners, his ears perked for any signs of disorder. He personally led several raids on what he called “hotbeds of prostitution,” and he denounced white suburbanites who came to Paterson to pursue ladies of the night. He donned a firefighter’s suit and busted up a bookmaking operation. He ordered the police to issue a warrant to the poet and Paterson native son Allen Ginsberg for smoking pot. Ginsberg, in town for a poetry reading, escaped to New York.

Nothing flustered Graves more than Paterson’s surplus of taverns. There were too damn many of them, about three hundred and fifty, give or take a stray moonshiner with a back porch brew strong enough to rip your gut out. The mayor attacked the jazz bars and gin joints, sometimes twenty on a block, as carriers of moral decay, seedy venues of gambling, brawling, and whoring. The very names of the bars—Cabin of Joy, Blue Danube, Polynesian Club, Bobaloo—evoked exotic, bacchanalian pleasures, which he felt threatened Paterson’s social equilibrium.

Graves was particularly concerned about the so-called ghetto bars and personally led raids on them to break up fights or ferret out other wrongdoing. Indeed, “checking” these bars, which entailed cops pushing, shoving, and threatening patrons, was a favorite method for maintaining the balance of terror between blacks and the authorities, however much observers decried these tactics as Gestapo-like.

Blacks took considerable pride in their rollicking circuit of jazz clubs and playhouses, burlesque shows and barrooms. They clustered at the bottom of Governor Avenue, known as “down the hill,” abutting the Passaic River and just outside Paterson’s cheerless Central Business District. Frank Sinatra and Nat “King” Cole had played in black Paterson. So had Lou Costello, the fleshy wit who was a native son. But for the black machine operators and silk dye workers, the seamstresses and secretaries, Paterson’s nightlife was not about glamour or celebrities. It was about loud music, hard drinking, and dirty dancing. They cashed their checks on Friday and had money to spend on the weekend. Young men on the make, dressed in dark suits and narrow black ties, some with razor blades in their pockets, danced the slop, the boogaloo, or the grind. Well-dressed young women, many of them domestics, flirted with their suitors. The revelers, sometimes en masse, sometimes in a trickle, strolled through the neon-lit, one-way streets long into the night, circulating through the Kit Kat Club, the Do Drop Inn, or the Ali Baba. When these clubs closed at 3 A.M., the party moved to after-hours clubs tucked behind darkened grocery stores or to “basement socials,” where entrants paid a quarter to the house, slipped downstairs with their bottle in a brown bag, and swayed with a partner beneath an undulating red light.

The most popular black club, the Nite Spot, stood on the corner of Governor and East Eighteenth Streets. Female impersonators gave it a racy edge, while a black tile floor with drizzles of gray, a cover charge, and a kitchen grill conferred a veneer of sophistication. The crowd grooved on the wooden dance floor to Alvin Valentine’s jazzy, sweet-tempered organ and sipped Dewar’s White Label Scotch and Johnnie Walker Red (which was smoother than Black). Managers allowed in “young blood,” or bucks under the age of twenty-one, while bartenders sneaked bottles of wine to youngsters at the back door, charging them double. Paterson’s most famous resident, the boxer Rubin Carter, gave the Nite Spot added cachet. He had his own table, Hurricane’s Corner.

Drinking holes for white Patersonians, if not exactly respectable, were more … decorous. They had less colorful names—Bruno’s, Kearney’s, Question Mark—and were typically called taverns. They were scattered through the Polish and Lithuanian neighborhoods of the city’s Riverside section, through Little Italy in the center of town, and through the Irish enclaves of South Paterson. They served cream ale, a flat brew made locally with a thick foamy top and a potent kick. Many of these taverns had sawdust on the floor, pool tables in the back, and grills in the kitchen. Patrons ate burgers, watched Friday-night boxing matches on black-and-white televisions, and threw darts. They cursed with Old World epithets.

The beery dens were in all neighborhoods and welcomed all comers. Gangsters and millworkers, politicians and merchants, nurses and hookers, blacks and whites, rich and poor—they all had their hangouts, they were out there somewhere, and Frank Graves could not stop them.

It was not as if he had nothing else to worry about. The exodus of industry, commerce, and the middle class had sent his city into a long downward spiral. Paterson, only 8.36 square miles, sits in the lowland loop of the Passaic River, its southern banks lined by abandoned redbrick cotton mills, empty factories, and rusting warehouses. At night, Main Street was deserted as street lamps cast islands of light on discount stores: John’s Bargain Store, ANY SHOE for $3.33, the five-and-ten. Displays of plastic shoes and acetate dresses were fragile remnants of a once-pulsating business district. Across Main Street stood Garrett Mountain, a camel’s hump of a hill that offered a view of the world beyond Paterson. When the smog cleared and the sun was out, residents could discern Manhattan’s metallic skyline, 15 miles southeast.

Graves’s campaign against the bars was, in fact, a battle against the city’s raucous history. Since its founding, Paterson had been the Wild West on the Passaic, where bare-knuckled industrialists converged with brawny immigrants and infamous scoundrels. Alexander Hamilton, smitten by the Great Falls of the Passaic River, founded Paterson in 1791 with the belief that water-powered mills would turn the city into a laboratory for industrial development. Initially, Paterson was not a city at all but a corporation, called the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufacturers, or SUM. The Panic of 1792 almost sank SUM, but it survived, and Paterson flourished as a freewheeling outpost of frontier industrialism.

Fueled by iron ore from nearby mines, charcoal from abundant forests, and coal from Pennsylvania, Paterson in the nineteenth century attracted inventors, romantics, and robber barons who made goods used across the country and beyond. In 1836 Sam Colt, unable to raise money for a factory by roaming the East Coast with a portable magic show, found backers in Paterson, where he manufactured his first revolver. John Holland, an Irish nationalist, built the first practical submarine in Paterson in 1878, his goal being “to blow the English Navy to hell.” (The Brits turned out to be principal buyers of the new weapon.)

It seemed that Patersonians believed anything was possible, reckless or otherwise. In the 1830s “Leaping” Sam Patch, a cotton mill foreman, became the only man to jump off the Niagara Falls successfully without a protective device. (He was less successful jumping off the Genesee Falls; his body turned up in a block of ice on Lake Ontario.) Wright Aeronautical Corporation undertook a more constructive if no less daring mission in 1927: it built a nine-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine that propelled Charles Lindbergh to Paris on the first solo Atlantic flight. Paterson’s most famous product was silk—enough to adorn all the aristocrats in Europe, if not the Victorian homes and furtive mistresses of the silk barons themselves. Silk lured thousands of European immigrants to Paterson. By 1900 they filled three hundred and fifty hot, clamorous mills, weaving 30 percent of all the silk produced in the United States.

Between 1840 and 1900, Paterson’s population increased by 1,348 percent, to 110,000 residents, making it the fastest-growing city on the East Coast. Newly arrived Germans, Irish, Poles, Italians, Russians, and Jews carved out sections of the city, and ethnic taverns followed. By 1900 Paterson had more than four hundred bars, where tipplers bought cheap, locally brewed beer and reminisced about the old country. Even in the 1950s, long after the immigrant waves had been assimilated, the Emil DeMyer Saloon, in the oldest part of the city, north of the river, hung out a sign that read: “French, Dutch, German, and Belgian Spoken Here.”

The bars, of course, were also seen as contributing to alcoholism, broken marriages, and lost weekends. Wives complained to the priest of Saint John the Baptist Cathedral, William McNulty, that their husbands were quaffing down their wages. Dean McNulty, who led the church for fifty-nine years until he died in 1922, would patrol the bars on Friday nights and swat the guzzlers home with his wooden walking stick.

Booze was hardly enough to calm the tensions that stirred in the crowded three-family frame tenements. The factory laborers, with their dye-stained fingers and arthritic backs, chafed at the excesses of the rich. In 1894 Paterson’s largest silk manufacturer, Catholina Lambert, built a hulking medieval castle near the top of Garrett Mountain, hiring special trains to bring four hundred guests to its opening reception. But in the streets below, vandalism was rampant, strikes common, and political passions high. In 1900, when Angelo Bresci, a Paterson anarchist, returned to his homeland of Italy and murdered King Humbert I, a thousand anarchists in Paterson gathered to celebrate. Between 1850 and 1914, Paterson was the most strike-ridden city in the nation. The strife reached its brutal climax in 1913, when a five-month strike left gangs of workers and police roaming the streets and attacking one another. Paterson’s silk industry, and the town itself, never recovered.

While World War II spurred a brief economic revival, mechanization threw weavers out of work, and textile factories needing skilled labor moved to the South. Wright Aeronautical went from a wartime peak of sixty thousand employees to five thousand, then moved to the suburbs. The Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufacturers dissolved in 1946. The Great Falls became a favorite spot for suicides and murder.

Lacking leadership and vision, Paterson continued its long economic slide in the 1960s, and like other cities in New Jersey, it became a wide-open rackets town. Bookies ran the wirerooms in a club on lower Market Street, placing bets on horse races and football games. The most popular form of gambling, the grease that lubricated the Paterson economy, was the “numbers.” It cost as little as a quarter or even a dime, and everyone played, including the cops. Bettors dropped off their money at a storefront, typically a bar but perhaps a bakery or grocery. Bets were made on the closing number of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the winning numbers from a horse race, or the New York Daily News’s circulation number, which was published on the back page in each edition. The following day, the two-bit gamblers either griped about their bad luck or picked up their winnings, typically six hundred times their bet, meaning $60 on a ten-cent wager or $150 on a quarter. Win or lose, they put down another bet. Numbers runners ferried the cash to the mobsters, who controlled the game, and the small business owners who collected the cash got a cut. It was another way for the bustling taverns to stay in business, but it did little to help Paterson regain its glory.

In On Paterson, Christopher Norwood wrote this elegy for the city in the middle 1960s: “The mills, the redbrick buildings where people produced commodities and became commodities themselves, still stand in Paterson, but most are abandoned now. The looms are no more, their noisy, awkward machinery long vandalized or sold for scrap. Vines, weeds and sometimes whole trees have grown through their stark walls, the walls unadorned except for small slits, outlined in a contrasting brick pattern, left for windows.”