Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Driven»

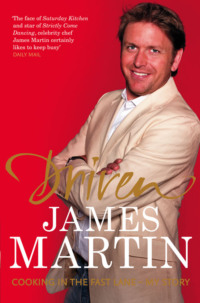

Driven

James Martin

COOKING IN THE FAST LANE – MY STORY

This book is dedicated to all the people I’ve met, loved, lost, punched, argued with, kicked, sworn at, bought from, sold to, hired, sacked, spoken about, written about, fallen out with, hated, worked with and had a drink with. You have shaped my life and this book.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

1 Skateboarding Around the Kitchen Table

2 Arcade Games and Aston Martins: The V8 Vantage

3 Boys’ Toys

4 The Castle Howard Rubbish Run: The Ferrari 308

5 Les Voitures (Merde) De Mon Pere

6 Bmxs, Bunny-Hops and Brownies

7 Bikes and Trikes

8 Philip Schofield is Definitely Not a Chicken: The Fiat 126

9 France in an Hgv

10 ‘Extra-Curricular’: The White Vauxhall Nova

11 The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

12 A New Start in the New Forest

13 The Car-Fanatic Father I Never Had

14 How a Kit Car Saved My Life: The Westfield, Part I

15 Screen Tests: The Westfield, Part II

16 Track Days

17 Ready, Steady…Now Don’t Do it Again: The Lotus Elise, Part I

18 The Perils of Public Transport

19 A Very Royal Scandal: The Lotus Elise, Part II

20 The Audi Convert

21 A Considered Buy: The Ferrari 360, Part I

22 My Other Car’s a Ferrari: The Vauxhall Corsa

23 It’s Only Metal: The Ferrari 360, Part II

24 A Kick in the Nuts: The Ferrari 360, Part III

25 Cars and Bond Girls

26 Jags, Ranges, Bikes and Boats

27 My First Oldie: The Gullwing

28 Follow that Car! The Ferrari 355 Again

29 The Time of My Life: The Dbs 007

30 Strictly Knackered

31 Miss England and the Saturday Kitchen Cars

32 Campervans

33 A Leap of Faith: The Maserati A6Gcs

34 The Finish Line

Index

Photo

Acknowledgments

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Most people probably don’t know about my car obsession, but it’s quite serious, and I’ve had it a long time. From my earliest memory, my life has been dedicated to the pursuit of two passions – cooking and motors. To be honest, I can’t remember which came first; the two have always gone hand in hand. As a kid, I was either helping out in the kitchens of Castle Howard, where my father was catering manager, or driving a tractor around the fields of our farm. If I wasn’t flambéing chicken livers at catering college, I was circling Golf GTis in AutoTrader and dreaming of Ferraris. And if I wasn’t working 18-hour shifts in some of the most punishing kitchens in London, I was spending what little I’d earned on some ridiculous kit car with no roof and big shiny exhaust pipes. Every job I’ve ever had has been to finance wheels of some description. I know that most people associate me with cooking, but for people who really know me, cars are probably the first thing that spring to mind. Put it this way: I’ve got a beautiful big kitchen at home, but my garages, all three of them, are more impressive. My whole life has been wrapped up with cars in some way. Knowing that, it’s easier to understand why this has been one of the most monumental years of my life. This year has seen the realisation of one of my dreams. This year I took part in the world’s ultimate road race.

I was just 22 when I first heard of the Mille Miglia road race, a 1,000 mile rally through the medieval streets and squares of Italy, from Brescia to Rome and back again. At the time, I was head chef at the Hotel Du Vin in Winchester and was constantly surrounded by mega-rich people with mega-money cars. I’d just acquired a fantastic little two-seater kit car of my own, so when I overheard talk about a world-famous classic car race, my ears pricked up. Not long after, I came across an article about it and from there I was hooked.

Enzo Ferrari called it ‘the world’s greatest road race’. Only in Italy would they allow three hundred vintage sports cars to drive at breakneck speeds on public roads, competing against one another and against the clock, cheered on by women, children, young men, old men, local mayors and the police. It’s fast, loud and dangerous, and utterly intoxicating. I read about the Mille Miglia’s glory days when Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss battled it out, Moss ultimately claiming triumph in 1955 in his legendary Mercedes-Benz 300slr, completing the race in a staggering 10 hours 7 minutes and 48 seconds. I read about the horrific accidents, including the one that killed twelve spectators in 1957 and led to the annual event being scrapped on grounds of safety. Then I read about the race’s 1982 revival as an historic rally for vintage cars, a time trial rather than an out-and-out race. I wanted to go and see all the incredible machines, to hear the noise and feel the excitement. Right then and there I promised myself that one day, if it was the last thing I did, I would go and watch the Mille Miglia.

I never in my wildest dreams thought I’d actually get to drive in the thing. That seemed such an impossibility that it wasn’t even an ambition. Back in its heyday, if you were able to get hold of a car and some petrol, you could be out there going wheel to wheel with Moss and Fangio. Technically, it’s still open to anyone. Every year roughly two thousand people apply to take part in the race. Only around 350 are chosen, and it’s all based on the eligibility of the car. You can’t buy or muscle your way into the Mille Miglia, you have to be invited once you’ve applied. On the upside, that means it’s not full of rich brats and yuppies with too much money and no idea of style and sophistication. On the downside you need bags of money, because eligible cars don’t come cheap, and neither does getting them to the start ramp.

Fast-forward to 2005 and I was at the BBC to talk about a new cooking series. We were trying to brainstorm ideas but not coming up with anything. As an aside I mentioned the forthcoming Mille Miglia and how I would love to go to watch it because I was nuts about cars. Suddenly everyone in the room perked up and wanted to know more about the race and my car collection. They asked me to write a proposal for a programme based around my actually doing the race.

I had no idea what the proposal should look like, so I got in touch with a producer I knew. He said that the best thing to do wasn’t to try to put the race on paper, but to put it on film, to make a mini pilot so the BBC could get a feel for the cars, the places, the event. So two weeks later, there I was, standing next to the start ramp in Brescia, a camera in my face, shouting above the roar of an Alfa Romeo revving up behind me, ‘Forget Monaco, forget Formula One, this is the most amazing race in the world, the Mille Miglia, and next year I’m going to do it.’

A week after they got the pilot, the BBC came back with a yes. And that was it. I was doing the Mille Miglia. Not that any of us – me, the production company, the BBC – had even the first clue how to go about it. Production hired someone to sort out the logistics of the race, the application process, and everything related to the organisation of the race itself. The BBC set a budget but it was barely enough to cover the camera crew and the editing, so the car and a co-driver were most definitely going to have to come out of my own pocket. In fact, money got so tight so quickly that when it became clear I was going to have to hire support mechanics too and pay for their transport, food and accommodation I struck a deal with the producer. I said, ‘I’ll waive my fee if you pay for the support team.’ He agreed, no doubt thinking he was getting the better deal, but for once being paid nothing really did make sound financial sense. Not that earning nothing and borrowing vast sums of money to pay for cars I really can’t afford was anything new to me. Throughout my life I’ve seemed to make a habit of it, though I’ve never once had any regrets.

There were moments when I wasn’t convinced I was ever going to make it to the start line. At one point my car, a bright red 1948 Maserati A6GCS, one of only three made that year by the legendary Italian car manufacturer, looked worryingly like a two-year-old’s Lego set, i.e. in pieces, and lots of them. The bills for repair were adding up and the loan I took out in the first place to cover buying the car and getting it into the race was already bigger than the mortgage on my house. At one point the loan repayments alone were more than I used to earn in a year at Hotel Du Vin, when I first read about the race. But if it’s your dream, you’ve got to do it, right? For once, I actually agree with my dad, who always used to say that anything in life is possible, it just depends whether you’re prepared to work hard enough for it. And I’d worked hard for this. I’d spent my whole life working towards this point, absorbing everything there was to know about cars, hurtling through my life on four wheels and using all my hard-earned cash to fuel my passion. And now I can truly say that nothing comes close to the noise of thousands of over-excited Italians screaming and cheering as the cars throttle down the famous start ramp and charge off into the night, down the narrowest of cobbled streets, made narrower by the devoted crowds that line the way from start to finish – and this being Italy, there are no barriers separating cars and spectators; they don’t even close the roads for it. It’s the biggest collection of classic cars you’ll ever see, not sitting in a museum gathering dust but out on the road doing what they were built for. This three-day test of skill, stamina and decades-old metalwork is the ultimate adventure for any car fanatic. And I’m utterly proud that I’ve been a part of it.

Cars and food might not be an obvious combination to most people, but to me it all makes perfect sense. One just always seems to lead to the other and, as you’ll see, I’ve gone to ridiculous lengths for both. So while it may come as a surprise to hear me raving on about vintage cars and Italian rallies, rather than celeriac mash and spun sugar, you should know that every memory of every job, pay packet, place and person I can think of comes with a make and model number attached. Looking back, it’s easy to see how everything I’ve ever done has been leading me unswervingly to the start line of the world’s most famous road race. I hope the stories that follow will show you why entering the Mille Miglia has meant so much to me, and that you’ll enjoy reading about some of the best moments of my life.

1 SKATEBOARDING AROUND THE KITCHEN TABLE

It all started when I was seven years old. I was skateboarding around the kitchen table. I remember going round and round. I couldn’t get enough of the speed, the challenge, the skill, the going round and round.

We lived in an old farmhouse with a big kitchen which was always at the centre of everything. The kitchen was the hub of the family as well as the house. It was all pine inside, with a huge dresser, a big old butler’s sink and a big round pine table with pine chairs. The table sat ten and was always busy. People didn’t knock on the door of our house, they just walked straight into the kitchen and made themselves at home. It was a lovely place to be. That’s where my love of food started. If my mum wasn’t cooking, my dad was. Mealtimes were a big deal in our house, and Sunday lunch was the most important. The table would be packed for it. My grandparents would be there, my mum, my dad, my sister, my aunty, and me, on my skateboard.

As well as the big pine table, the other important feature of the kitchen was a big old Aga with a metal towel rail on the front of it. If you pulled on the towel rail quickly enough while stood on a skateboard, you could launch yourself with enough force to ride almost all the way round the kitchen table. What made the kitchen particularly suitable for skateboarding, though, was the floor. It had these cork tiles which with hindsight were horrible but at the time were perfect for skateboarding on. Ceramic tiles or lino would have been lethal: one pull on the Aga towel rail and you’d have been off with a broken neck. But the cork tiles, designed to stop nasty slips while holding a boiling pan, gave all the grip you needed for a successful run around the kitchen table.

Skateboarding was the ‘in’ thing at the time. Me and my mates were all into it, but me being me I couldn’t just have a normal skateboard. Firstly, I was very particular about which one I had. If I asked for a skateboard for Christmas I was very specific. Normal kids would write in their letter, ‘Dear Santa, please bring me a skateboard’; I would write, ‘Dear Santa, please bring me a skateboard, model XT47, blue, available from Halfords, priced £14.99.’ That way I’d be sure I was getting the right one. And it had to be the right one. I didn’t want a red one or a black one or a yellow one, I wanted a blue one. I didn’t want an XT20 or an XT40, it had to be the XT47. And if my granny asked my mum what I wanted, there was always the outfit to go with it. I had the full gear – the knee pads, the arm pads, the helmet.

Our little farming village had never seen anything like it. I looked a right pillock going down the road, slowly, on my skateboard dressed head to toe in all the get-up. I don’t think any of the other kids in the village had seen anything like it either. Me and my best mate David Coates used to skateboard together, but his wasn’t as good as mine because he would just write ‘skateboard’ on his list for Santa. David used to be way better than me at almost everything we did, but he never quite had the right gear. He may have been better at sport than me, but he never looked quite as good doing it. Yes, there was intense competition to have the best skateboard, the coolest BMX. It was like real life Top Trumps back then. It still is now, only with Ferraris.

Getting the right board and outfit was only the start of it though. I could never leave it as the standard board everyone else had, I had to ‘trick’ mine. It’s always been the way, no matter what I’ve owned: I’ve got to modify it, make it better. So every penny of the pocket money I used to earn mowing the lawns, doing a bit of gardening or helping out on the farm mucking out the pigs went on ‘improvements’.

We weren’t proper farmers, of course. With my dad’s catering manager post at Castle Howard came a house and some land which was pretty much useless for anything other than farming, so at various times we had pigs, cattle and chickens which me and my sister Charlotte, who’s a year younger than me, used to help out with. It wasn’t highly paid work – we were only seven and six – so when you spent you had to spend wisely. At the corner shop my 50p pay would buy me a Coke and a Mars bar (twice) and a handful of Floral gums. I hated Floral gums. They were, and still are, disgusting. They tasted like soap, but they were the only sweets my sister didn’t like, which made them good value. She’d have all the good sweets, which I’d nick off her; I’d have all the crap ones, which she wouldn’t come near. They might not have been pleasant, but they made the most of the money.

With only limited funds and a standard skateboard in need of ‘improvement’, some particularly creative thinking was required. I could work all year and I still wouldn’t be able to afford the proper (and eye-wateringly expensive) foot grips they sold in Halfords, so I cut two feet-shaped pieces out of some sandpaper in my dad’s shed and glued them to the top of my board with UHU. Careful saving of my hard-earned fifties meant I could just about afford the four new wheels I wanted – one red, two white, one blue – and, most important of all, the special tricked-out ball bearings required to do all the proper stunts. The only problem was, I couldn’t ride the bloody thing. I could barely stand up on it, never mind do stunts. I used to have to sit on it on my bum to go down hills. Which is why I did most of my skateboarding in the kitchen.

So there I was in the kitchen, in all the gear – knee pads, arm pads, helmet – looking like a pillock, holding on to the towel rail of the Aga. It was a Sunday lunchtime and everyone was in the kitchen, sitting round the table, which I was launching myself around again and again, making everyone dizzy and increasingly irritated. My grandfather was getting particularly annoyed as I tried, and more often than not failed, to circle the ten seated obstacles.

Of everyone around that table, my grandfather, my mum’s dad, was the least likely to put up with such antics. A former cricketer, a fast bowler, he used to play for Yorkshire with Freddie Trueman, he worked as a ticket man on the railway and was a proper no-nonsense Yorkshireman who didn’t really make allowances. He used to say things like ‘Get a proper job, play cricket.’ When we used to ‘play’ in his back garden, which always featured an absolutely perfect cricket pitch lawn, stripes and all, he’d bowl cricket balls at me at 150 miles an hour, overarm, like he was warming up against Botham in the nets. You learned quickly to give the ball a good hit to show you were trying, but not too hard because you knew that if you really whacked it and it went over the hedge the next ball would be coming straight at your head. Needless to say, I hate cricket.

So, everyone was chatting away, trying to ignore me but getting more and more annoyed as I went round and round, almost but not quite making it all the way round the table because, maybe, someone had pushed their chair out and I’ve crashed into it. On my fourth or fifth attempt, my grandfather had finally had enough.

‘So, son,’ he said with a force that put me off what could have been my first full flying lap of the day, ‘what do you want to do when you get older?’

I stopped my skateboard right next to him and without even thinking about it I replied that I wanted to be a chef.

My dad, being a catering manager, knew a thing or two about chefs and he was nodding and saying, ‘That’s all right that. Good career. Hard work, but a good career.’ Granddad wasn’t looking quite so impressed, but spurred on by my dad’s approval I added, ‘I want to be a head chef at 30, have my own restaurant at 35 and have a Ferrari when I’m 40.’

My granddad turned to me, a look of disgust on his face, and in his firm Yorkshire accent he said, ‘You want to get a bloody proper job, play cricket. You’ll never get all that, not being a chef.’

Now, anyone who knows me will tell you that I’m not one to shy away from a challenge. They’ll also tell you that I’m the hardest-working person they know. All my friends will say that I put in more hours, more effort and more passion than anyone else they’ve ever met and that if I say I’m going to do something, I usually do it. Even so, through all the years of working 18-hour days, living on the breadline, begging, borrowing and stealing (literally) to survive, standing up to jumped-up little French chefs, being battered and abused in restaurant kitchens over the years, being ripped off in business and being mistaken for a fool more than once, I would never in my wildest dreams have imagined the truth: that I’d achieve all the boastful ambitions I voiced as a seven-year-old on a skateboard by the time I was 24.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.