Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «The Thousandth Floor»

Copyright

First published in the USA by HarperCollins Publishers Inc., in 2016

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by HarperCollins Children’s Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers ltd, 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF.

Copyright © Alloy Entertainment and Katharine McGee 2016

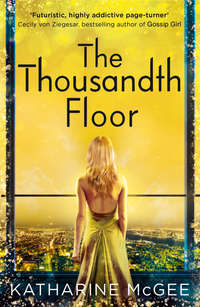

Cover photographs © Ilina Simeonova/Trevillion Images (woman figure); Westend61/Getty (window); Hongqi Zhang/Alamy (cityscape); Shutterstock.com (woman head).

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2016

Katharine McGee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008179977

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008179960

Version: 2016-08-04

For Lizzy

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Avery

Leda

Rylin

Eris

Watt

Avery

Leda

Avery

Eris

Rylin

Watt

Leda

Avery

Eris

Rylin

Avery

Watt

Eris

Leda

Rylin

Eris

Avery

Eris

Watt

Rylin

Watt

Leda

Eris

Leda

Avery

Rylin

Leda

Avery

Eris

Rylin

Leda

Avery

Watt

Rylin

Eris

Leda

Watt

Rylin

Avery

Leda

Eris

Avery

Watt

Leda

Avery

Watt

Rylin

Eris

Leda

Avery

Leda

Watt

Rylin

Eris

Watt

Rylin

Leda

Eris

Avery

Leda

Rylin

Eris

Rylin

Leda

Watt

Avery

Mariel

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

November 2118

THE SOUNDS OF laughter and music were dying down on the thousandth floor, the party breaking up by bits and pieces as even the rowdiest guests finally stumbled into the elevators and down to their homes. The floor-to-ceiling windows were squares of velvety darkness, though in the distance the sun was quietly rising, the skyline turning ocher and pale pink and a soft, shimmering gold.

And then a scream cut abruptly through the silence as a girl fell toward the ground, her body falling ever faster through the cool predawn air.

In just three minutes, the girl would collide with the unforgiving cement of East Avenue. But now—her hair whipped up like a banner, the silk dress snapping around the curves of her body, her bright red mouth frozen in a perfect O of shock—now, in this instant, she was more beautiful than she had ever been.

They say that before death, people’s lives flash before their eyes. But as the ground rushed ever faster toward her, the girl could think only of the past few hours, the path she’d taken that ended here. If only she hadn’t talked to him. If only she hadn’t been so foolish. If only she hadn’t gone up there in the first place.

When the dock monitor found what remained of her body and shakily pinged in a report of the incident, all he knew was that the girl was the first person to fall from the Tower in its twenty-five years. He didn’t know who she was, or how she’d gotten outside.

He didn’t know whether she’d fallen, or been pushed, or whether—crushed by the weight of unspoken secrets—she’d decided to jump.

AVERY

Two months earlier

“I HAD A great time tonight,” Zay Wagner said as he walked Avery Fuller to the door of her family’s penthouse. They’d been down at the New York Aquarium on the 830th floor, dancing in the soft glow of the fish tanks and familiar faces. Not that Avery cared much about the aquarium. But as her friend Eris always said, a party was a party, right?

“Me too.” Avery tilted her bright blond head toward the retinal scanner, and the door unlocked. She offered Zay a smile. “Night.”

He reached for her hand. “I was thinking maybe I could come in? Since your parents are away and everything …”

“I’m sorry,” Avery mumbled, hiding her annoyance with a fake yawn. He’d been finding excuses to touch her all night; she should have seen this coming. “I’m exhausted.”

“Avery.” Zay dropped her hand and took a step back, running his fingers through his hair. “We’ve been doing this for weeks now. Do you even like me?”

Avery opened her mouth, then fell silent. She had no idea what to say.

Something flickered over Zay’s expression—irritation? confusion? “Got it. I’ll see you later.” He retreated to the elevator, then turned back, his eyes traveling over her once more. “You looked really beautiful tonight,” he added. The elevator doors closed behind him with a click.

Avery sighed and stepped into the grand entryway of her apartment. Back before she was born, when the Tower was under construction, her parents had bid aggressively to get this place—the entire top floor, with the only two-story foyer in the entire structure. They were so proud of this entryway, but Avery hated it: the hollow way it made her footsteps echo, the glinting mirrors on every surface. She couldn’t look anywhere without seeing her reflection.

She kicked off her heels and walked barefoot toward her room, leaving the shoes in the middle of the hallway. Someone would pick them up tomorrow, one of the bots, or Sarah, if she actually showed up on time.

Poor Zay. Avery did like him: he was funny in a loud, fizzy way that made her laugh. But she just didn’t feel anything when they kissed.

But the only boy Avery did want to kiss was the one she never, ever could.

She stepped into her room and heard the soft hum as the room comp whizzed to life, scanning her vitals and adjusting the temperature accordingly. An ice water appeared on the table next to her antique four-poster bed—probably because of the champagne still turning in her empty stomach, though Avery didn’t bother asking. After Atlas skipped town, she’d disabled the voice function on the comp. He’d been the one to set it on the British accent and name it Jenkins. Talking to Jenkins without him was too depressing.

Zay’s words echoed in her head. You looked really beautiful tonight. He was just trying to give her a compliment, of course; he couldn’t have known how much Avery hated that word. All her life she’d been hearing how beautiful she was—from teachers, boys, her parents. By now the phrase had lost all meaning. Atlas, her adopted brother, was the only one who knew better than to compliment her.

The Fullers had spent years and a great deal of money conceiving Avery. She wasn’t sure how expensive she’d actually been to make, though she guessed her value at slightly below that of their apartment. Her parents, who were both of middling height with ordinary looks and thinning brown hair, had flown in the world’s leading researcher from Switzerland to help mine their genetic material. Somewhere in the million combinations of their very average DNA, they found the single possibility that led to Avery.

She wondered, sometimes, how she would’ve turned out if her parents had made her naturally, or just screened for diseases like most people on the upper floors. Would she have inherited her mom’s skinny shoulders, or her father’s big teeth? Not that it mattered. Pierson and Elizabeth Fuller had paid for this daughter, with honey-colored hair and long legs and deep blue eyes, her dad’s intelligence, and her mom’s quick wit. Atlas always joked that stubbornness was her one imperfection.

Avery wished that was the only thing wrong with her.

She shook out her hair, yanked it into a loose bun, and walked purposefully from her room. In the kitchen she swung open the pantry door, already reaching for the hidden handle to the mech panel. She’d found it years ago during a game of hide-and-seek with Atlas. She wasn’t even sure whether her parents knew about it; it wasn’t as if they ever set foot in here.

Avery pushed the metal panel inward, and a ladder swung down into the narrow pantry space. Clutching the skirts of her ivory silk gown with both hands, she folded herself into the crawl space and started up, counting the rungs instinctively in Italian as she did, uno, due, tre. She wondered if Atlas had spent any time in Italy this year, if he’d even gone to Europe at all.

Balancing on the top rung, she reached to release the trapdoor and stepped eagerly into the wind-whipped darkness.

Beneath the deafening roar of the wind, Avery heard the rumbling of various machines on the roof around her, huddled under their weatherproof boxes or photovoltaic panels. Her bare feet were cold on the metal slabs of the platform. Steel supports arced from each corner, joining overhead to form the Tower’s iconic spire.

It was a clear night, no clouds in the air to dampen her eyelashes or bead into moisture on her skin. The stars glittered like crushed glass against the dark vastness of the night sky. If anyone knew she was up here, she’d be grounded for life. Exterior access over the 150th floor was forbidden; all the terraces above that level were protected from the high-speed winds by heavy panes of polyethylene glass.

Avery wondered if anyone had ever set foot up here besides her. There were safety railings along one side of the roof, presumably in case maintenance workers came up, but to her knowledge, no one ever had.

She’d never told Atlas. It was one of only two secrets she had kept from him. If he found out, he would make sure she didn’t come back, and Avery couldn’t bear the thought of giving this up. She loved it here—loved the wind battering her face and tangling her hair, bringing tears to her eyes, howling so loud that it drowned out her own wild thoughts.

She stepped closer to the edge, relishing the twist of vertigo in her stomach as she gazed out over the city, the monorails curving through the air below like fluorescent snakes. The horizon seemed impossibly far. She could see from the lights of New Jersey in the west to the streets of the Sprawl in the south, to Brooklyn in the east, and farther, the pewter gleam of the Atlantic.

And beneath her bare feet lay the biggest structure on earth, a whole world unto itself. How strange that there were millions of people below her at this very moment, eating, sleeping, dreaming, touching. Avery blinked, feeling suddenly and acutely alone. They were strangers, all of them, even the ones she knew. What did she care about them, or about herself, or about anything, really?

She leaned her elbows on the railing and shivered. One wrong move could send her over. Not for the first time, she wondered how it would feel, falling two and a half miles. She imagined it would be strangely peaceful, the feeling of weightlessness as she reached terminal velocity. And she’d be dead of a heart attack long before she hit the ground. Closing her eyes, she tilted forward, curling her silver-painted toes over the edge—just as the back of her eyelids lit up, her contacts registering an incoming ping.

She hesitated, a wave of guilty excitement crashing over her at the sight of his name. She’d done so well avoiding this all summer, distracting herself with the study abroad program in Florence, and more recently with Zay. But after a moment, Avery turned and clattered quickly back down the ladder.

“Hey,” she said breathlessly when she was back in the pantry, whispering even though there was no one around to hear. “You haven’t called for a while. Where are you?”

“Somewhere new. You’d love it here.” His voice in her ear sounded the same, warm and rich as always. “How’re things, Aves?”

And there it was: the reason Avery had to climb into a windstorm to escape her thoughts, the part of her engineering that had gone horribly wrong.

On the other end of the call was Atlas, her brother—and the reason she never wanted to kiss anyone else.

LEDA

AS THE COPTER crossed the East River into Manhattan, Leda Cole leaned forward, pressing her face against the flexiglass for a better look.

There was always something magical about this first glimpse of the city, especially now, with the windows of the upper floors blazing in the afternoon sun. Beneath the neochrome surface Leda caught flashes of color where the elevators shot past, the veins of the city pumping its lifeblood up and down. It was the same as ever, she thought, utterly modern and yet somehow timeless. Leda had seen countless pics of the old New York skyline, the one people always romanticized. But compared to the Tower she thought it looked jagged and ugly.

“Glad to be home?” her mom asked carefully, glancing at her from across the aisle. Leda gave a curt nod, not bothering to answer. She’d barely spoken to her parents since they’d picked her up from rehab earlier this morning. Or really, since the incident back in July that had sent her there.

“Can we order Miatza tonight? I’ve been craving a dodo burger for weeks,” her brother, Jamie, said, in a clear attempt to cheer her up. Leda ignored him. Jamie was only eleven months older, about to start his senior year, but he and Leda weren’t all that close. Probably because they were nothing alike.

With Jamie everything was simple and straightforward, and he never seemed to worry that much at all. He and Leda didn’t even look alike—where Leda was dark and spritely like their mom, Jamie’s skin was almost as pale as their dad’s, and despite Leda’s best efforts he always looked sloppy. Right now he was sporting a wiry beard that he’d apparently spent the summer growing.

“Whatever Leda wants,” Leda’s dad replied. Sure, because letting her choose their takeout would make up for everything.

“I don’t care.” Leda glanced down at her wrist. Two tiny puncture wounds, remnants of the monitor bracelet that had clung to her all summer, were the only evidence of her time at Silver Cove. Which had been located perversely far from the ocean, in central Nevada.

Not that Leda could really blame her parents. If she’d walked in on the scene they’d witnessed back in July, she would have sent her to rehab too. She’d been an utter mess when she arrived there: vicious and angry, hyped up on xenperheidren and who knew what else. It had taken a full day of what the other girls at Silver Cove called “happy juice”—a potent IV drip of sedatives and dopamine—before she even agreed to speak with the doctors.

As the drugs seeped slowly from Leda’s system, though, the acrid taste of her resentment had begun to fade. Shame flushed over her instead: a sticky, uncomfortable shame. She’d always promised herself that she would remain in control, that she wouldn’t be one of those pathetic addicts they showed in the health class holos at school. Yet there she was, with an IV drip taped into her vein.

“You okay?” one of the nurses had said, watching her expression.

Never let them see you cry, Leda had reminded herself, blinking back tears. “Of course,” she managed, her voice steady.

Eventually Leda did find a sort of peace at rehab: not with her worthless psych doctor, but in meditation. She spent almost every morning there, sitting cross-legged and repeating the mantras that Guru Vashmi intoned. May my actions be purposeful. I am my own greatest ally. I am enough in myself. Occasionally Leda would open her eyes and glance around through the lavender smoke at the other girls in the yoga tepee. They all had a haunted, hunted look about them, as if they’d been chased here and were too afraid to leave. I’m not like them, Leda had told herself, squaring her shoulders and closing her eyes again. She didn’t need the drugs, not the way those girls did.

Now they were only a few minutes from the Tower. Sudden anxiety twisted in Leda’s stomach. Was she ready for this—ready to come back here and face everything that had sent her into a tailspin in the first place?

Not everything. Atlas was still gone.

Closing her eyes, Leda muttered a few words signaling her contacts to open her inbox, which she’d been checking nonstop since she left rehab this morning and got service again. Three thousand accumulated messages instantly pinged in her ears, invitations and vid-alerts cascading over one another like musical notes. The rumble of attention was oddly soothing.

At the top of the queue was a new message from Avery. When are you back?

Every summer, Leda’s family forced her to come on their annual visit “home” to Podunk, middle-of-nowhere Illinois. “Home is New York,” Leda would always protest, but her parents ignored her. Leda honestly didn’t even understand why her parents wanted to keep visiting year after year. If she’d done what they did—moved from Danville to New York as newlyweds, right when the Tower was built, and slowly worked their way up until they could afford to live in the coveted upper floors—she wouldn’t have looked back.

Yet her parents were determined to return to their hometown every year and stay with Leda and Jamie’s grandparents, in a tech-dark house stocked with nothing but soy butter and frozen meal packets. Leda had actually enjoyed it back when she was a kid and it felt like an adventure. As she got older, though, she started begging to stay behind. She dreaded being around her cousins, with their tacky mass-produced clothing and eerie contactless pupils. But no matter how much she protested, she never could worm her way out of going. Until this year.

I’m back now! Leda replied, saying the message aloud and nodding to send it. Part of her knew she should tell Avery about Silver Cove: they’d talked a lot in rehab about accountability, and asking friends for help. But the thought of telling Avery made Leda clutch at the seat beneath her until her knuckles were white. She couldn’t do it; couldn’t reveal that kind of weakness to her perfect best friend. Avery would be polite about it, of course, but Leda knew that on some level she would judge her, would always look at Leda differently. And Leda couldn’t handle that.

Avery knew a little of the truth: that Leda had started taking xenperheidren occasionally, before exams, to sharpen her thinking … and that a few times she’d taken some stronger stuff, with Cord and Rick and the rest of that crowd. But Avery had no idea how bad it had gotten toward the end of last year, after the Andes—and she definitely didn’t know the truth about this summer.

They pulled up to the Tower. The copter swayed drunkenly for a moment at the entrance to the seven-hundredth-floor helipad; even with stabilizers, it still faltered in the gale-force winds that whipped around the Tower. Then it made a final push and came to a rest inside the hangar. Leda unfolded herself from her seat and clattered down the staircase after her parents. Her mom was already on a call, probably muttering about a deal gone bad.

“Leda!” A blond whirlwind hurtled forward to engulf her in a hug.

“Avery.” Leda smiled into her friend’s hair, gently disentangling herself. She took a step back and looked up—and faltered momentarily, her old insecurities rushing back. Seeing Avery again was always a shock to the system. Leda tried not to let it bother her, but sometimes she couldn’t help thinking how unfair it was. Avery already had the perfect life, up in the thousandth-floor penthouse. Did she really have to be perfect too? Seeing Avery next to the Fullers, Leda could never quite believe that she’d been created from their DNA.

It sucked sometimes, being best friends with the girl too flawless to come from nature. Leda, on the other hand, probably came from a night of tequila shots on her parents’ anniversary.

“Want to get out of here?” Avery asked, pleading.

“Yes,” Leda said. She would do anything for Avery, although this time she didn’t really need to be coaxed.

Avery turned to embrace Leda’s parents. “Mr. Cole! Mrs. Cole! Welcome home.” Leda watched as they laughed and hugged her back, opening up like flowers in sunlight. No one was immune to Avery’s spell.

“Can I steal your daughter?” Avery asked, and they nodded. “Thanks. I’ll have her home by dinner!” Avery called out, her arm already in Leda’s, tugging her insistently toward the seven-hundredth-floor thoroughfare.

“Wait a sec.” Next to Avery’s crisp red skirt and cropped shirt, Leda’s end-of-rehab outfit—a plain gray T-shirt and jeans—looked positively drab. “I want to change if we’re going out.”

“I was thinking we’d just go to the park?” Avery blinked rapidly, her pupils darting back and forth as she summoned a hover. “A bunch of the girls are hanging out there, and everyone wants to see you. Is that okay?”

“Of course,” Leda said automatically, shoving aside the prickle of annoyance she felt that they weren’t hanging out one-on-one.

They walked out the helipad’s double doors and into the thoroughfare, a massive transportation hub that spanned several city blocks. The ceilings overhead glowed a bright cerulean. To Leda, they seemed just as beautiful as anything she’d seen on her afternoon hikes at Silver Cove. But Leda wasn’t the type to look for beauty in nature. Beauty was a word she reserved for expensive jewelry, and dresses, and Avery’s face.

“So tell me about it,” Avery said in that direct way of hers, as they stepped onto the carbon-composite sidewalks that lined the silver hover paths. Cylindrical snackbots hummed past on enormous wheels, selling dehydrated fruit and coffee pods.

“What?” Leda tried to snap to attention. Hovers streamed down the street to her left, their movements darting and coordinated like a school of fish, colored green or red depending on whether they were free. She instinctively moved a little closer to Avery.

“Illinois. Was it as bad as usual?” Avery’s eyes went distant. “Hover call,” she said under her breath, and one of the vehicles darted out of the pack.

“You want to hover all the way to the park?” Leda asked, dodging the question, trying to sound normal. She’d forgotten the sheer volume of people here—parents dragging their children, businesspeople talking loudly into their contacts, couples holding hands. It felt overwhelming after the curated calm of rehab.

“You’re back, it’s a special occasion!” Avery exclaimed.

Leda took a deep breath and smiled just as their hover pulled up. It was a narrow two-seater with a plush eggshell interior, floating several centimeters above the ground thanks to the magnetic propulsion bars in its floor. Avery took the seat across from Leda and keyed in their destination, sending the hover on its way.

“Maybe next year they’ll let you miss it. And then you and I can travel together,” Avery went on as the hover dropped into one of the Tower’s vertical corridors. The yellow track lighting on the tunnel walls danced in strange patterns across her cheekbones.

“Maybe.” Leda shrugged. She wanted to change the subject. “You’re insanely tan, by the way. That’s from Florence?”

“Monaco. Best beaches in the world.”

“Not better than your grandmother’s house in Maine.” They’d spent a week there after freshman year, lying outside in the sun and sneaking sips of Grandma Lasserre’s port wine.

“True. There weren’t even any cute lifeguards in Monaco,” Avery said with a laugh.

Their hover slowed, then began to move horizontally as it turned onto 307. Normally coming to a floor so low would count as serious downsliding, but visits to Central Park were an exception. As they pulled to a stop at the north-northeast park entrance, Avery turned to Leda, her deep blue eyes suddenly serious. “I’m glad you’re back, Leda. I missed you this summer.”

“Me too,” Leda said quietly.

She followed Avery through the park entrance, past the famous cherry tree that had been reclaimed from the original Central Park. A few tourists were leaning on the fence that surrounded it, taking snaps and reading the tree’s history on the interactive touch screen alongside it. There was nothing else left of the original park, which lay beneath the Tower’s foundations, far below their feet.

They turned toward the hill where Leda already knew their friends would be. Avery and Leda had discovered this spot together in seventh grade; after a great deal of experimentation, they’d concluded it was the best place to soak in the UV-free rays of the solar lamp. As they walked, the spectragrass along the path shifted from mint green to a soft lavender. A holographic cartoon gnome ran through a park on their left, followed by a line of squealing children.

“Avery!” Risha was the first to catch sight of them. The other girls, all reclining on brightly colored beach towels, glanced up and waved. “And Leda! When did you get back?”

Avery plopped in the center of the group, tucking a strand of flaxen hair behind one ear, and Leda settled down next to her. “Just now. I’m straight from the copter,” she said, pulling her mom’s vintage sunglasses out of her bag. She could have put her contacts on light-blocking mode, of course, but the glasses were sort of her signature. She’d always liked how they made her expression unreadable.

“Where’s Eris?” she wondered aloud, not that she particularly missed her. But you could usually count on Eris to show up for tanning.

“Probably shopping. Or with Cord,” said Ming Jiaozu, a suppressed bitterness in her tone.

Leda said nothing, feeling caught off guard. She hadn’t seen anything about Eris and Cord on the feeds when she checked this morning. Then again, she could never really keep up with Eris, who’d dated—or at least messed around with—nearly half the boys and girls in their class, some of them more than once. But Eris was Avery’s oldest friend, and came from old family money, and because of that she got away with pretty much anything.

“How was your summer, Leda?” Ming went on. “You were with your family in Illinois, right?”

“Yeah.”

“That must have been awful, being in the middle of nowhere like that.” Ming’s tone was sickly sweet.

“Well, I survived,” Leda said lightly, refusing to let the other girl provoke her. Ming knew how much Leda hated talking about her parents’ background. It was a reminder that she wasn’t from this world the way the rest of them were, that she’d moved up in seventh grade from midTower suburbia.

“What about you?” Leda asked. “How was Spain? Did you hang out with any of the locals?”

“Not really.”

“Funny. From the feeds, it looked like you made some really close friends.” In her mass-download on the plane earlier, Leda had seen a few snaps of Ming with a Spanish boy, and she could tell that something had happened between them—from their body language, the lack of captions under the snaps, most of all from the flush that was now creeping up Ming’s neck.

Ming fell silent. Leda allowed herself a small smile. When people pushed her buttons, she pushed back.

“Avery,” Jess McClane said, leaning forward. “Did you end things with Zay? I ran into him earlier, and he seemed down.”

“Yeah,” Avery said slowly. “I mean, I think so? I do like him, but …” she trailed off halfheartedly.

“Oh my god, Avery. You really should just do it, and get it over with!” Jess exclaimed. The gold bangles on her wrists glimmered in the solar panel’s light. “What are you waiting for, exactly? Or maybe I should say, who are you waiting for?”

“Give it a rest, Jess. You can’t exactly talk,” Leda snapped. People always made comments like that to Avery, because there was nothing else to really criticize her about. But it made even less sense coming from Jess, who was a virgin too.

“As a matter of fact, I can,” Jess said meaningfully.

A chorus of squeals erupted at that—“Wait, you and Patrick?” “When?” “Where?”—and Jess grinned, clearly eager to share the details. Leda leaned back, pretending to listen. As far as the girls all knew, she was a virgin too. She hadn’t told anyone the truth, not even Avery. And she never would.

It had happened in January, on the annual ski trip to Catyan. Their families had been going for years: at first just the Fullers and the Andertons, and then once Leda and Avery became such good friends, the Coles too. The Andes were the best skiing left on earth; even Colorado and the Alps relied almost exclusively on snow machines these days. Only in Chile, on the highest peaks in the Andes, was there enough natural snow for true skiing anymore.