Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth and the Coming of King James»

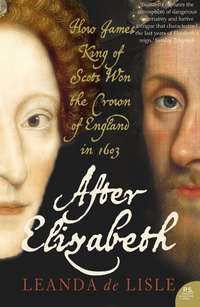

AFTER ELIZABETH

The Death of Elizabeth and the Coming of King James

LEANDA DE LISLE

DEDICATION

For Peter,Rupert, Christian and Dominic,my cornerstones.

EPIGRAPH

‘If you can look into the seeds of time,And say which grain will grow and which will not’,

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

GENEALOGY

MAP

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1 ‘The world waxed old’ The twilight of the Tudor dynasty

CHAPTER 2 ‘A babe crowned in his cradle’ The shaping of the King of Scots

PART TWO

CHAPTER 3 ‘Westward … descended a hideous tempest’ The death of Elizabeth, February–March 1603

CHAPTER 4 ‘Lots were cast upon our land’ The coming of Arthur, March–April 1603

CHAPTER 5 ‘Hope and fear’ Winners and losers, April–May 1603

CHAPTER 6 ‘The beggars have come to town’ Plague and plot in London, May–June 1603

PART THREE

CHAPTER 7 ‘An anointed King’ James and Anna are crowned, July–August 1603

CHAPTER 8 ‘The God of truth and time’ Trial, judgement and the dawn of the Stuart age

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

P.S. IDEAS, INTERVIEWS & FEATURES …

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Q AND A WITH LEANDA DE LISLE

LIFE AT A GLANCE

TOP FIVE, BOTTOM FIVE

A WRITING LIFE

ABOUT THE BOOK

A LETTER TO THE READER BY LEANDA DE LISLE

READ ON

IF YOU LOVED THIS, YOU MIGHT LIKE …

FIND OUT MORE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

NOTES

PRAISE

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

GENEALOGY

The Descendants of Henry VII

The Royal Houses of Portugal and Spain

The House of Talbot

The House of Cavendish

MAP

PART ONE

‘There are more that look, as it is said,to the rising than to the setting sun’

Elizabeth I

CHAPTER ONE

‘The world waxed old’

The twilight of the Tudor dynasty

SIR JOHN HARINGTON arrived at Whitehall in December 1602 in time for the twelve-day Christmas celebrations at court. The coming winter season was expected to be a dull one, though the new Comptroller of the Household, Sir Edward Wotton, was trying his best to inject fresh life into it. Dressed from head to toe in white he had laid on dances, bear baiting, plays and gambling. The Secretary of State, Sir Robert Cecil, lost up to £800 a night – an astonishing sum, even for one who, according to popular verse, ruled ‘court and crown’. Behind the scenes, however, courtiers gambled for still higher stakes. Harington observed that Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudors, was sixty-nine and although she appeared in sound health ‘age itself is a sickness’.1 She could not live forever and after a reign of forty-four years the country was on the eve of change.

To Elizabeth, Harington was ‘that witty fellow my godson’. Courtiers knew him for his invention of the water closet, his translations of classical works, his scurrilous writings on court figures and his mastery of the epigram, which was then the fashionable medium for comment on court life. In the competition for Elizabeth’s favour, however, courtiers were expected to reflect her greatness not only in learning and wit but also in their visual magnificence. They did so by dressing in clothes ‘more sumptuous than the proudest Persian’. A miniature depicts Harington as a smiling man in a cut silk doublet and ruff, his long hair brushed back to show off a jewelled earring that hangs to his shoulder. Even a courtier’s plainest suits were worn with beaver hats and the finest linen shirts, gilded daggers and swords, silk garters and show roses, silk stockings and cloaks.2

This brilliant world was a small one, though riven by scheming and distrust. ‘Those who live in courts, must mark what they say,’ one of Harington’s epigrams warned, ‘Who lives for ease had better live away.’3 Harington, typically, knew everyone at Whitehall that Christmas, either directly or through friends and relations.4 Elizabeth herself was particularly close to the grandchildren of her aunt Mary Boleyn, known enviously as ‘the tribe of Dan’. The eldest, Lord Hunsdon, was the Lord Chamberlain responsible for the conduct of the court. His sisters, the Countess of Nottingham, and Lady Scrope, were Elizabeth’s most favoured Ladies of the Privy Chamber. But Harington also had royal connections, albeit at one remove. His estate at Kelston in Somerset had been granted to his father’s first wife, Ethelreda, an illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII. When Ethelreda died childless the land had passed to John Harington senior. He remained loyal to Elizabeth when she was imprisoned following a Protestant-backed revolt against her Catholic sister Mary I, named after one of its leaders as Wyatt’s revolt, and when Elizabeth became Queen she rewarded him with office and fortune, making his second wife, Harington’s mother Isabella Markham, a Lady of the Privy Chamber. It was the hope of acquiring such wealth and honour that was the chief attraction of the court.

Harington once described the court as ‘ambition’s puffball’ – a toadstool that fed on vanity and greed, but it was one that had been carefully cultivated by the Tudor monarchy. With no standing army or paid bureaucracy to enforce their will the monarchy had to rely on persuasion. They used Arthurian mythology and courtly displays to capture hearts, while patronage appealed to the more down-to-earth instincts of personal ambition. Elizabeth could grant her powerful subjects the prestige that came with titles and orders; the influence conferred by office in the Church, the military, the administration of government and the law; there were also posts at court or in the royal household. She could bestow wealth with leases on royal lands and palaces, offer special trading licences and monopolies or bequeath the ownership of estates confiscated from traitors.5 Those who gained most from Elizabeth’s patronage were themselves patrons, acting as conduits for the Queen’s munificence.

Harington and his friends worked hard to ingratiate themselves with the great men at court, often spending years, as he complained, in ‘grinning scoff, watching nights and fawning days’.6 When a great patron fell from grace a decade of personal and financial investment could be lost. The precise standing of all senior courtiers was therefore tracked and discussed by gossips and intelligencers. Every tiny fluctuation in their fortunes stoked what one observer described as, ‘The court fever of hope and fear that continuously torments those that depend upon great men and their promises.’7 The ‘fever’ reached a pitch when the health of the monarch was a cause for concern since their death could mean a complete revolution in government.

Harington arrived at court having completed, on 18 December, his Tract on the Succession to the Crown – a subject on which the pulse of the nation was now said to ‘beat extremely’ but which was strictly forbidden. As Harington had recorded in his tract, Elizabeth had ‘utterly suppressed the talk of an heir apparent’ in the year of his birth, 1561, ‘saying she would not have her winding sheet set up before her face’. Her concern, he explained, was ‘that if she should allow and permit men to examine, discuss and publish whose was the best title after her, some would be ready to affirm that title to be good afore hers’.8

Forty years earlier there had been those who had claimed that Elizabeth’s Catholic cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, had a superior claim to the English throne; others that it belonged to her Protestant cousin Catherine Grey. Both claimants had since died: Catherine in a country house prison in 1568, Mary on the executioner’s block in 1587. But their sons, James VI of Scotland and Lord Beauchamp had succeeded them as rivals to her throne, together with more recent candidates such as James’s cousin, Arbella Stuart, and the Infanta Isabella of Spain. The dangers to Elizabeth were such that the publication of any discussion of the succession had been declared an act of treason by Parliament only the previous winter. Her advancing age meant, however, that an heir would soon have to be chosen, if not by her, then by others.

Harington had dedicated his tract to his preferred choice, James VI, the Protestant son of Mary, Queen of Scots. As the senior descendant of Henry VIII’s elder sister, Margaret, and her first husband, James IV, he was Elizabeth’s heir by the usual dynastic rules of primogeniture, but James was far from being the straightforward choice that this suggests.

The Stuart line of the Kings of Scots was barred from the succession under the will of Henry VIII, which was backed by Act of Parliament. James was also personally excluded under a law dating back to the reign of Edward III precluding those born outside ‘the allegiance of the realm of England’. His hopes rested on the fact that the claims of his rivals were equally problematic. Elizabeth had declared Catherine Grey’s son, Lord Beauchamp, illegitimate, and, as men had delved ever deeper into the complex question of the right to the throne, the numbers of potential heirs had proliferated. By 1600 the sometime writer, lawyer and spy Thomas Wilson had counted ‘twelve competitors that gape for the death of that good old princess, the now queen’.9 Spain, France and the Pope all had their preferred candidates while the English were divided in their choice by religious belief and contesting ambitions.

Courtiers feared that the price of Elizabeth’s security during her life would be civil war and foreign invasion on her death – but the future was also replete with possibilities. A new monarch drawn from a weak field would need to acquire widespread support to secure their position against their rivals. That meant opening up the royal purse: there would be gifts of land, office and title. Harington’s tract was a private gift to James made in the hope of future favour. The gamble was to invest in the winning candidate – for as Thomas Wilson observed ‘this crown is not likely to fall for want of heads that claim to wear it, but upon whose head it will fall is by many doubted’.10

The Palace of Whitehall, built by Cardinal Wolsey and extended by Henry VIII, sprawled on either side of King Street, the road linking Westminster and Charing Cross. On the western side were the buildings designed for recreation: four covered tennis courts, two bowling alleys, a cockpit and a gallery for viewing tournaments in the great tiltyard. Up to 12,000 spectators would come to watch Elizabeth’s knights take part in the annual November jousts held to celebrate her accession. When the jousts were over the contestants’ shields were hung in a gallery, where, that summer, the visiting German Duke of Stettin-Pomerania had been directed to admire the insignia of Elizabeth’s last great favourite, Robert Devereux, the second Earl of Essex. He had broken fifty-seven lances in the course of fighting fifteen challengers during the Accession Tilts of 1594. There was, however, much more to Essex than his prowess at the tilt. He had represented the aspirations of Harington’s generation, born after Elizabeth became Queen and kept from office by her stifling conservatism.

Elizabeth is still remembered as the Queen who defied the Armada in 1588, and the figure of Gloriana as encapsulated in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene the following year. But as one court servant warned, this was to see her ‘like a painted face without a shadow to give it life’11. Elizabeth had reached the apogee of her reign in the 1580s. Thereafter came a decline that lasted longer than the reigns of her siblings, Mary I and Edward VI, put together. Her victory over the Armada was tarnished by the costs of the continuing war with Spain and the woman behind the divine image had grown old. To Essex’s vast following of young courtiers Elizabeth was a dithering old woman, dominated by her Treasurer Lord Burghley and his corrupt son, Sir Robert Cecil. Her motto ‘Semper Eadem’ (I never change), once perceived as a promise of stability, came to be taken as a challenge.

When Burghley died in August 1598, Essex hoped to become the new force in Elizabeth’s government but within weeks a long simmering rebellion in Ireland had turned into a war of liberation. Essex, as Elizabeth’s most experienced commander, was made Lord Deputy of Ireland and sent to confront the rebel leader, Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone. Instead, in September 1599, in defiance of royal orders, Essex arranged a truce and returned to court. Elizabeth was furious and as Essex fell into disgrace he turned his hopes to finding favour with the candidate he hoped to succeed her. In February 1601 he led 300 soldiers and courtiers in a palace revolt to force her to name James VI of Scotland her heir and overthrow Robert Cecil together with his principal allies, Henry Brooke, Lord Cobham and Sir Walter Ralegh. The revolt quickly failed and the Earl was executed, but Essex remained a popular figure in national memory. Stettin’s journal records that ballads dedicated to Essex were being ‘sung and played on musical instruments all over the country, even in our presence at the royal court though his memory is condemned as that of a man having committed high treason’.12 They mourned England’s ‘jewel … The valiant knight of chivalry’, destroyed, it was said, by the malevolence of the Cecil faction.

Brave honour graced him still,Gallantly, gallantly,He ne’er did deed of ill,Well it is known But Envy, that foul fiend,Whose malice ne’er did endHath brought true virtue’s friendUnto his thrall.13

Beneath the smiles of the courtiers as they played cards that Christmas lay the deep bitterness of old enemies; those who had admired Essex and those who had rejoiced in his downfall.

The gallery above the tiltyard where Essex had jousted was linked to the second group of buildings through a gatehouse over King Street. Here, in the Privy Gardens, thirty-four mythical beasts sat on thirty-four brightly coloured poles overlooking the low-railed pathways. The buildings had a similarly fairy-tale quality. They were decorated in elaborate paintwork, the Great Hall in chequerwork and the Privy Gallery in black and white grotesques. The theme of these distorted animal, plant and human forms extended into the interior where they were highlighted with gold on the wood pillars and panelling. The visiting Duke of Stettin thought the ceilings rather low and the rooms gloomy. Elizabeth’s bedroom, which overlooked the Thames ‘was very dark’ with ‘but little air’. Nearby in Elizabeth’s cabinet, where she wrote her letters, Stettin observed a marvellous silver inkstand and ‘also a Latin prayer book that the queen had written nicely with her own hand, and, in a beautiful preface, had dedicated to her father’.14

Harington had been granted an audience with the Queen soon after his arrival at Whitehall. As usual he was escorted from the Presence Chamber, where courtiers waited bareheaded to present their petitions, along a dark passage and into the Privy Chamber where his godmother awaited him.15 A mural by Hans Holbein the Younger dominated the room. The massive figure of Henry VIII stood, hand on hips, gazing unflinchingly at the viewer. His third wife Jane Seymour, the mother of his son Edward VI, was depicted on his left and above him his mother, Elizabeth of York, with his father, Henry VII. The mural boasted the continuity of the Tudor dynasty, a silent reproach to the childless spinster Harington now saw before him. Contemporaries remarked often on Elizabeth’s similarity to her grandfather. When she was young they saw it in her narrow face and the beautiful long hands of which she was so proud. As she grew older she developed her grandfather’s wattle, a ‘great goggle throat’ that hung from her chin.16 But she did not now look merely old. She appeared seriously ill.

Harington was shocked by what he saw and frightened for the future. Elizabeth had been increasingly melancholic since the Essex revolt, but he was now convinced that she was dying. He confided his thoughts in a letter to the one person he trusted: his wife, Mary Rogers, who was at home in Somerset caring for their nine children.

Sweet Mall,

I herewith send thee what I would God none did know, some ill bodings of the realm and its welfare. Our dear Queen, my royal godmother, and this state’s natural mother, doth now bear signs of human infirmity, too fast for that evil which we will get by her death, and too slow for that good which she shall get by her releasement from pains and misery. Dear Mall, How shall I speak what I have seen, or what I have felt? – Thy good silence in these matters emboldens my pen … Now I will trust thee with great assurance, and whilst thou dost brood over thy young ones in the chamber, thou shalt read the doings of thy grieving mate in the court …17

Elizabeth received Harington seated on a raised platform. Her ‘little black husband’ John Whitgift, the Archbishop of Canterbury whose plain clerical garb contrasted so starkly with her bejewelled gowns and spangled wigs, was beside her.* It was believed that Elizabeth used her glittering costumes to dazzle people so they ‘would not so easily discern the marks of age’, but if so, she no longer considered them enough. Increasingly afraid that any intimation of mortality would attract dangerous speculation on her successor she had taken to filling out her sunken cheeks with fine cloths and was also ‘continually painted, not only all over the face, but her very neck and breast also, and that the same was in some places near half an inch thick’.18 There were some things, however, that make-up could not hide. When Elizabeth spoke it was apparent that her teeth were blackened and several were missing. Foreign ambassadors complained it made her difficult to understand if she spoke quickly. But during Harington’s audience this was not a problem; her throat was so sore and her state of mind so troubled that she could barely speak at all.

The rebellion in Ireland that had cost Elizabeth so much in men, money and peace of mind was near its end. The arch rebel Tyrone was offering his submission, but it brought Elizabeth no joy; memories of Essex’s betrayals were crowding in. She whispered to Whitgift to ask Harington if he had seen Tyrone? Harington had witnessed Essex making the truce with Tyrone in 1599 and later met him in person. He still trembled at the memory of Elizabeth’s fury with him about it when he had returned to England, and he now answered her carefully, saying only, ‘I had seen him with the Lord Deputy.’ At this, Elizabeth looked up with an expression of anger and grief and replied ‘Oh, now it mindeth me that you was one who saw this man elsewhere,’ and she began to weep and strike her breast. ‘She held in her hand a golden cup, which she often put to her lips; but in sooth her heart seemed too full to lack more filling,’ Harington told his wife.

As the audience drew to a close Elizabeth rallied and she asked her godson to come back to her chamber at seven o’clock and bring some of the light-hearted verses and witty prose for which he was famous. Harington dutifully returned that evening and read Elizabeth some verses. She smiled once but told him, ‘When thou dost find creeping time at thy gate, these fooleries will please thee less; I am past my relish for such matters. Thou seeest my bodily meat doth not suit me well; I have eaten but one ill-tasted cake since yesternight.’19 The following day Harington saw Elizabeth again. A number of men had arrived at her request only to be dismissed in anger for appearing without an appointment: ‘But who shall say that “Your Majesty hath forgotten”?’ Harington asked Mall.

No one dared to voice openly the seriousness of Elizabeth’s condition, but Harington did find ‘some less mindful of what they are soon to lose, than of what they may perchance hereafter get’.20 He told his wife he had attended a dinner with the Archbishop and that many of Elizabeth’s own clerics appeared to be ‘well anointed with the oil of gladness’. But the spectacle of Elizabeth’s misery amidst the feasting pricked Harington’s conscience. In his Tract on the Succession he had wasted no opportunities to dwell on the unpopularity of her government and to contrast her failings as an aged Queen with James VI’s youth, vigour and masculinity. Now he could not suppress memories of all the kindness she had shown him, ‘her watchings over my youth, her liking to my free speech and admiration of my little learning … have rooted such love, such dutiful remembrance of her princely virtues, that to turn askant from her condition with tearless eyes, would stain and foul the spring and fount of gratitude’.21

Harington’s eyes, however, tear-filled or not, remained as fixed on the future as those of everyone else, and he was comforted by the realisation that his examination of the succession issue had been completed with exquisite timing.

The question of the succession had dominated the history of the Tudor dynasty and would shape events to come. The first Tudor king, Henry VII, had been a rival claimant to a reigning monarch until his army killed Richard III at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. The victory came at the end of a long period of civil strife in which Harington’s great-grandfather, James Harington, was allied with the losing side – an error that cost the family much of their land in the north of England. Henry was fearful that such families would rise up against him if a rival candidate to his crown emerged and so he worked hard to achieve a secure succession. He had two sons to ensure the future of his line and he bolstered his claim by creating a mythology that anchored the Tudors in a legendary past.

Henry VII claimed that his ancestor, Owen Tudor, was a direct descendant of Cadwallader, supposedly the last of the British kings. This made the Tudors the heirs of King Arthur and through them, it was said, Arthur would return.22 Henry even named his eldest son Arthur, but the boy died aged fifteen not long after his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. It was thus his second son, Henry VIII, who inherited the crown, as well as his brother’s bride. Henry and Catherine had a daughter, the future Mary I, but no sons. Henry saw this lack of a male heir as an apocalyptic failure fearing that the inheritance of the throne by a mere queen regnant could plunge England back into civil war. He became convinced that God had punished him for having married his brother’s wife and sought an annulment from the Pope. When the Pope, under pressure from Catherine’s Hapsburg nephew, Charles V, denied it to him, he made himself the head of the Church in England. Justifications for Henry’s new title were found in the various ‘histories’ of Arthur, but his actions had coincided with the revolution in religious opinion in Europe begun by the German monk, Martin Luther. One of Henry’s chief researchers was a keen follower of Luther’s teachings and although Henry had once written against Luther he chose to reward Thomas Cranmer’s service in ‘discovering’ the royal supremacy by making him Archbishop of Canterbury. Centuries of Catholic culture and belief were to be overturned in favour of new Protestant ideas as Henry divorced Catherine, declared Mary illegitimate and married ‘one common stewed whore, Anne Boleyn’, as the Abbot of Whitby called her.

The Reformation changed England forever. The simple fact that the country was no longer part of the supra-national Roman Church encouraged a stronger sense of separateness from the Continent and enabled Henry to develop a full-blooded nationalism to which his dynasty was central. Elizabeth, the child of this revolution, was not, however, her father’s heir for long. Anne Boleyn was executed before she was three years old and Elizabeth, already a bastard in the eyes of the Catholic Church, was declared illegitimate by her father in order that any children of the marriage to his new love, Jane Seymour, should take precedence over her, as she had once done over her sister, Mary. When Jane Seymour had her son, Edward, in 1537, it seemed to Henry that the question of the succession was answered. As Henry had no further children by the three wives that succeeded Jane Seymour he eventually restored Elizabeth and Mary in line to the succession after Edward, in default of Edward’s issue or any further children by his last wife, Catherine Parr. His decision was confirmed in the Act of Succession in 1544 – the year before Elizabeth had made her father the gift of the prayer book that the German Duke saw on her desk.

The Act of Succession allowed the King to alter the succession by testament, that is, in his will. This was significant for Henry’s will wrote into law who Elizabeth’s heirs should be if all his children died without issue. Henry had sought Elizabeth’s heirs amongst the descendants of his sisters, Margaret of Scotland and Mary Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk. Margaret, the eldest, had married James IV of Scotland, who was killed fighting the English at Flodden in 1513. Their son, James V, died after losing a later battle against the English and left his infant daughter, Mary Stuart, as Queen of Scots. She should have been Elizabeth’s heir under the laws of primogeniture, but Henry’s will disinherited the Stuart line in favour of that of the Suffolks in vengeance for the Stuart enmity to England and the Scots’ refusal to marry their Queen to his son.

Harington’s tract explained that the Scots had feared that if Mary Stuart married Prince Edward their country would have become a mere province of England. In the winter of 1602/3 the English had similar concerns that if James VI of Scotland inherited the throne their country might be subsumed into a new kingdom called ‘Britain’. Machiavelli had argued that changing a country’s name was a badge of conquest and Harington warned James that ‘some in England fear the like now’. The name Britain had an unpleasantly Celtic ring and people believed that the creation of a new united kingdom could nullify English Common Law.

Many believed that James was also precluded from the succession by the medieval law excluding heirs born outside ‘the allegiance of the realm’.23 Edward VI had drawn attention to this law in drawing up his will in 1553, which had also excluded the Stuart line. Harington’s tract attempted to counter it by arguing that Scotland was not really a foreign country at all, since all Englishmen considered it ‘subject to England in the way of homage’. But it was a view with which James himself was unlikely to concur.*

Elizabeth had inherited the throne in 1558, following the death of her Catholic half-sister, Mary I. As a woman the twenty-five-year-old queen fitted awkwardly into the chivalric legend of the Tudors being the heirs to Arthur but Elizabeth proved adept at reshaping it. From the day of her coronation, where she greeted the crowds with ‘cries, tender words, and all other signs which argue a wonderful earnest love of most obedient servants’, Elizabeth worked to build an image that was at once feminine and supremely majestic. She became the mother of her people, the wife married to her kingdom, the unobtainable love object of the knights and nobles; a Virgin to rival the Queen of Heaven to whom medieval England had once been dedicated, the summation of the dynasty’s mythology.

Even in 1558, however, courtiers were considering the vital question of who would succeed her. The last three reigns had seen violent swings in religious policy, from Henry VIII’s Reformation, to the radical Protestantism of Edward VI, to the Catholicism of Mary. No one had believed Elizabeth would be able to bring stability to a kingdom still bitterly divided by religion unless she produced an heir to guarantee the future of her Protestant supporters: men such as Elizabeth’s closest adviser, William Cecil, the future Lord Burghley, who had sat on Edward VI’s Privy Council, but lost his post when Mary I succeeded him. A petition urging Elizabeth to marry was drawn up by the House of Commons on the first day of her first parliament. Her reply was that she preferred to remain unmarried. Whether she intended this to be her last word on the subject is questionable, but, in the event, the dangers of making a bad or divisive choice would always outweigh any advantages of love and companionship. Fear and jealousy arose in one quarter or another whenever a potential bridegroom looked to be a likely candidate for her hand. Harington, however, could not see that Elizabeth’s decision might be a consequence of their own prejudice that a woman was invariably ruled by her husband. Instead he shared the widespread view that her disinclination to marry was the result of some personal failing.

Harington claimed that Elizabeth had a psychological horror of the state of marriage and ‘in body some indisposition to the act of marriage’, but he admitted that she had made the world think that she might marry until she was fifty years old and ‘she has ever made show of affection, and still does to some men which in court we term favourites’.24 These flirtations or dissimulations took some of the pressure off her to produce an actual spouse, but in the absence of one she was continually pushed to name a successor. It was only with hindsight Harington realised that Elizabeth had given her definitive answer, that she would never name an heir, in August of 1561, the year when she was confronted by the claims of her Suffolk heir, the Protestant Lady Catherine Grey, and her Catholic Stuart rival, Mary, Queen of Scots.