Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Bloom»

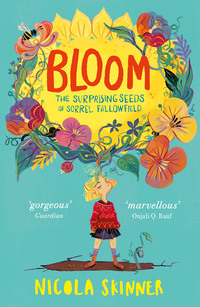

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Text copyright © Nicola Skinner 2019

Illustrations copyright © Flavia Sorrentino 2019

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Nicola Skinner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008297404

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008297411

Version: 2020-02-14

For Ben, who made this possible,

and Polly, who started it all off

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

This is a Warning.

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

One Year On

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

Books by Nicola Skinner

About the Publisher

IT’S NOT OFTEN you open a brand-new book to be told that it’s dangerous. But if you want the facts, and nothing but the facts, then this is a book with peril in its pages.

Well, technically, there might be peril in its pages. No one’s been able to prove anything. But still, the risks are there. Which means you need to read this page carefully before skipping off to Chapter 1.

No one is safe. Girls. Boys. Mums. Dads. Sisters. Brothers. Aunts. Uncles. Even those great-great-apparently-you’re-related-but-you-can’t-remember-how relatives you see once a year. Yep, even them.

You’re all in fate’s firing line now.

That’s because just holding this book and touching this paper has unfortunately left you, and everyone you know, potentially exposed to a substance that is, according to the scientists, ‘highly volatile, medically unregulated and impossible to cure’.

Or, as a confused-looking nurse put it to me once: ‘We’ve never seen anything like this before, love.’

So be prepared.

Over the next few days you might experience some unusual sensations. You could be running a bath before bedtime and want to drink it, not sit in it.

You might experience some unusual pains in some unusual places.

And finally – really, it’s nothing to be alarmed about – you might develop some, ahem, growths about your body.

But wait! Don’t fling the book away in horror! Come back! The chances of this happening to you too are super small. Roughly one in a million, or a billion. (Or one in a hundred. I’m not brilliant with decimals.) Honestly, it’s extremely unlikely anything will happen to you, and even if it does, there’s literally no point rushing off to the bathroom to scrub your hands.

Because it’s not your hands you need to worry about.

But look – try not to worry. Even if you are infected at least you won’t be the only one. It happened to us too. We all look a little weird here.

Or, as Mum would say diplomatically, ‘Haven’t we grown, Sorrel?’

And yes, that is my name. Mum has a thing about fresh herbs. It could have been worse, I suppose. She also loves parsley.

WHEN THE NEWSPAPERS and journalists first got hold of my story they wrote a lot of lies. The main ones were:

1. I was the child of a broken home.

2. Mum was a terrible single mother.

3. With a background like mine, it wasn’t any wonder I did what I did.

None of them was true – well, apart from Mum being a single mum. But it wasn’t her fault my dad had done a runner when I was a baby. Yet one of the headlines stuck in my head. I did come from a broken home.

Oh, not in the way they meant it, in the ‘I wore ragged trousers and brushed my teeth with sugar’ sort of way. But our house did feel worn out and broken down – something was always going wrong.

If you’d ever popped in, you’d have felt it too. The tick of the clock in the hallway would follow you around the house like it was tutting at you. The tap in the kitchen would go drip, drip, drip as if it was crying about something. If you sat down in front of the telly, it would lose sound halfway through whatever was on, as if it had gone into a monumental sulk and wasn’t speaking to anyone ever again. Ever.

There was a ring of black mould round the whole bath, our curtains were constantly pinging off their rods in some desperate escape mission and every time we flushed the loo the pipes would moan and groan at what we’d made them swallow. Oh yes, if you visited our house, you’d want to leave within seconds. You’d garble out an excuse, like: ‘Er, just remembered … I promised Mum I was going to hoover the roof today! Gotta go!’ And you’d get away as fast as you could.

Apart from my best friend Neena, not many people stayed long at our home.

And guess what it was called?

Cheery Cottage.

To be honest, though, I didn’t blame anyone that ran away. Because it wasn’t just the damp and the taps and the protesting pipes. It was more than all of that. It was the feeling in the house. And it was everywhere.

A gloomy glumness. A grumpy grimness. A grimy greyness. Cheery Cottage always felt cross and unhappy about something, and there was almost nothing this mood didn’t infect. It inched into everything, from the saggy sofa in the lounge, to the droopy fake fern in the hallway, which always looked as if it was dying of thirst, even though it was plastic.

And – worst of all – this misery sometimes seeped into Mum too. Oh, she’d never say as much, but I’d know. It was in her when she sat at the kitchen table, staring into space. It was in her when she shuffled downstairs in the mornings. I’d look at her. She’d look at me. And in the scary few seconds before she finally smiled, I’d think: It’s spreading.

But what could I do to fix things? I wasn’t a plumber. I was the shortest kid in our year, so I couldn’t reach the curtain poles. When it came to fixing the telly, all I knew was the old Whack and Pray method.

Instead, I had a different solution. And it was to follow this very simple rule:

Be good at school and be good at home, and do what I was told in both.

So, that’s what I did.

I was good at being good.

I was so good, Mum regularly ran out of shoeboxes in which to put my Sensible Child and School Rule Champion certificates.

I was so good, trainee teachers came to me to clear up any questions they had about Grittysnit School rules. Like:

Are pupils allowed to sprint outside?

(Answer: never. A slight jog is allowed if you are in danger – for example, if you are being chased by a bear – and even then, you must obtain written permission twenty-eight days in advance.)

Are you allowed to smile at Mr Grittysnit, our headmaster?

(Answer: never. He prefers a lowered gaze as a mark of respect.)

Has he always been so strict and scary?

(Answer: technically, this is not a question about school rules, but seeing as you’re new, I will let you off, just this once. And yes.)

I was so good, I was Head of Year for the second year running.

I was so good, my nickname at school was Good Girl Sorrel. Well, it had been Good Girl Sorrel, until sometime around the beginning of Year Five when Chrissie Valentini had changed it ever so slightly to ‘Suck-up Sorrel’. But I never told the teachers.

That’s how good I was.

And every time I came home from school with the latest proof, Mum would smile and call me her Good Girl. And that broken feeling would leave her and sneak back into the corners of the house.

For a while.

AND THEN, ON the first day of Year Six last September, something else broke too. Something I was quite fond of. My life.

It was the patio’s fault.

I’d let myself in from school. Mum was still working, the lucky thing, at The Best Job In The World, and wouldn’t get back for another two and a half hours. I planned to unwind by cleaning the kitchen, polishing my school shoes and doing my homework, because that was how I rolled.

Now, Mum wasn’t a big fan of me being home alone, but she worked full-time every day and didn’t get back till 5.45 p.m. We could only afford three days of After-school Club: Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. On Tuesdays, I went to Neena’s house after school. (Who, for a while, depending on which news programme was on, was either my gormless best friend, evil partner in crime, evil best friend or gormless partner in crime.)

Anyway, Mondays were my home-alone afternoons. On Monday mornings, Mum would always say: ‘Don’t burn the house down, and make sure you do your homework.’ As if I needed telling. Who knew exactly what she should be doing at any given time? Who had written Sorrel’s Stupendous Schedule?

I had, that’s who. My Stupendous Schedule played a big part in my being good. It’s sooo much easier to toe the line when you have a row of neat little boxes waiting to be ticked.

So there I was. Wiping sticky marmalade patches off our table. Emptying the dishwasher. Opening the back door to air the kitchen, which always smelled damp.

Once I’d done all that, it was 4.25 p.m. I had just a few more precious moments of leisure time before I had to crack on with my homework, and I knew exactly how to spend them.

I went to my rucksack and took out the letter which had been given to us at the end of school that very day. And this time, I didn’t skim it, surrounded by noisy classmates. I devoured every single word.

This is what it said:

Are the buttons always shiny on your blazer?

Do you regularly come home with Perfect Behaviour reports?

Could YOU be the winner of the school competition to find the Grittysnit Star of the Year?

There’s only one way to find out.

Enter my GRITTYSNIT STAR competition for the chance to be crowned THE MOST AMAZING GRITTYSNIT STAR OF THE ENTIRE SCHOOL AND LITTLE STERILIS at the end of term.

You will also win a seven-day family holiday in the Lotsa Rays Holiday Resort in Portugal. (Prize kindly donated by local travel agency Breakz Away.)

A family holiday in the sun! I’d never been abroad before, let alone on a plane. Mum always said money was a bit too tight for that. As if our money was an uncomfortable jumper.

On the letter, someone – probably the school secretary, Mrs Pinch – had drawn four little matchstick figures sunbathing on a beach. They were holding ice-cream cones and smiling at each other.

They looked happy.

I read on.

The winning GRITTYSNIT STAR will possess that special something that makes an ideal Grittysnit child.

I held my breath. What?

Each child will be judged on their ability to obey the school rules every second of the day.

I gasped in delight. That was me!

I did a quick mental calculation. There were sixty children in each year at Grittysnits. I’d be up against 419 other entrants. Or would I? I had six full years’ practice of obeying school rules. The odds were in my favour. Most kids in Reception and the early years could barely tie their own shoelaces, let alone mind their pees and, for that matter, their queues.

Winning that holiday would be like taking candy from a baby. I almost felt guilty as I mentally marked the number of competitors down. Them’s the breaks, kids.

The most important thing to remember is that the Grittysnit Star will be a living embodiment of our school motto, BLINKIMUS BLONKIMUS FUDGEYMUS LATINMUS. Or, in English …

I didn’t even have to read the English translation, I knew it so well. Looking up for a moment, I caught sight of my reflection in the kitchen window. Standing solemnly in front of me was a short, round, pale and freckly girl, her hair (the washed-out yellow of mild Cheddar) scraped back in a bun. She returned my gaze confidently, as if to say, ‘School motto? Cut me and I bleed school motto.’

Together, we chanted: ‘May obedience shape you. May conformity mould you. May rules polish you.’

The tap dripped sadly.

I read on.

The lucky winner will also enjoy other special privileges. These will include:

1. Having your own chair on the staff stage during school assemblies.

2. Never having to queue for lunch.

3. A massive badge (in regulation grey) which says:

What, you want more? That’s the problem with children these days it’s all take, take, take.

May the best child win.

Now, go and do your homework.

Your headmaster,

Mr Grittysnit

I put the letter down and took a big shaky breath. This was my destiny. Window girl and I looked solemnly at each other, as if bound by a silent pact.

Holding the letter as gently as if it was made of glass, I walked over to the fridge. I wanted to fix it there with a magnet so I could see it every day. But finding a space would not be easy. Already the fridge was plastered with yellowing bills, old recipes Mum tore out of magazines …

And, of course, that photo of us on our most recent summer holiday, taken just a fortnight before. It showed us on a small pebbly beach, huddled under a blanket, beneath a sky as grey as the bags under Mum’s eyes.

I stared at that photo, remembering. How the caravan had smelled of somebody else’s life that we’d wandered into by mistake. How Mum had spent the whole week begging me not to break anything. How it had rained for six days straight and then, just as we’d boarded the coach back to Little Sterilis, the sun had come out.

Which had made everything worse somehow.

Mum had spent the whole journey back – all five hours of it – with her forehead squished up against the window, staring at the blue sky like it was someone else’s birthday cake and she knew she wouldn’t get a slice.

Next to the photo was our calendar for the year ahead. I saw that Mum had marked our summer holidays on it already. CARAVAN, she’d written, in thick red ink. No exclamation marks. No smiley faces.

To be honest, it looked more like a threat than a holiday.

But if I won the Grittysnit Star competition, we could have a proper family holiday, somewhere sunny. Somewhere else. My yearning hardened into determination. All I had to do was be perfect for the next eight weeks.

No sweat.

I’d just fixed Mr Grittysnit’s letter over the photo, feeling immense relief as Mum’s troubled frown disappeared, when …

SLAM! The back door whipped open with a bang.

My heart hammered with fright. Who’s there?

But it was no one. Just a gust of wind and a door nearly swinging off its hinges. I must not have shut it properly after airing the kitchen earlier.

The wind roared in and seemed to fill the entire kitchen with anger. I felt as if I was standing in a room of invisible fury. On legs as wobbly as cooked spaghetti, I staggered over to shut the door and force the wind out.

Something white and fluttery flew over my shoulder.

I shrieked and ducked down.

Is a pigeon trapped in our kitchen?

I looked closer. It wasn’t a white pigeon, all claws and feathers. It was Mr Grittysnit’s letter! The wind had ripped it off the fridge and it was flying frantically about the room. When I jumped up to catch it, it darted out of reach, as if invisible blustery hands had snatched it away. I just caught a glimpse of the stick figures hovering in mid-air, their smiles turned to frozen grimaces, before they flapped and fluttered …

… out of the doorway and into our backyard.

I WANTED THAT letter. It would spur me on, a promise of better days. I took a deep breath and followed it outside.

I did a quick scan of the patio. It didn’t take long. Everything seemed the same. The two plastic chairs we never sat in. Weeds pushing up between the concrete paving slabs. And the tall weeping willow tree, right at the back, casting its shadow over our house.

I’d have been weeping too if I looked like that.

Its grey trunk was smothered in bright red hairy growths that looked like boils. Its branches dragged on the concrete as if it was hanging its head in misery. Even its leaves were ugly – black and withered and lifeless. Really, the tree didn’t so much grow as squat at the end of our garden, like a dying troll with a skin condition. Mum said it was diseased. I’d say.

And there was no sign of Mr Grittysnit’s letter. I was about to give it up for lost when a fluttering movement at the base of the tree caught my eye. It had somehow got wrapped round one of the tree’s withered branches. I could just about make out the words Each child will be judged and one stick figure pinned underneath a bunch of shrivelled leaves. I felt sorry for it. This wasn’t the holiday of a lifetime, lying under a septic tree in a damp backyard.

‘I’ll take that, thank you very much.’ I lifted up the branch gingerly – reluctant to catch its disease, whatever it was – and bent down to pick up the letter.

ZING! The air took on an electric charge and vibrated with a terrible force. The sounds in the garden became exaggerated with a horrid loudness. The rustling dead leaves in the branches above me were a booming rattle. A pigeon cooed and it sounded like a chainsaw. But more frightening than all of that were the gaps of silence between the sounds. They were eerie and powerful and strong.

It felt—

I’VE BEEN WAITING FOR YOU.

I spun on my heels. Who said that?

My heart thumped so loudly I could barely hear anything. Yet the patio was empty.

Icy sweat drenched my skin. Everything was real and unreal, too loud and too quiet at once.

Come on, Sorrel, breathe in and out, nice and slow. I calmed down enough to try to think. What had just happened? I’d only bent down to pick up the letter. Had the tree poisoned me, sent a hideous disease to my brain which had caused me to start hearing things? Or perhaps I’d had a rush of blood to the head when I’d bent down? Maybe I hadn’t had enough to eat. Maybe I should go into the kitchen and investigate the snack situation.

But what is that, moving near my feet? Rats?

There it was again!

But as I peered around me, shaking with fear, I realised there wasn’t anything black and wriggly next to my feet.

The movement had come from under my feet.

As if there was a … thing. Underneath the concrete.

Turning over.

Down there.

‘Hello?’

I sounded like a baby lamb bleating alone on a hill.

‘Is anyone there?’

The windows in the house gave me blank stares.

RUN, I told myself. NOW!

I managed one step away from the tree when the patio slab under my feet moved up and down, as if something deep down in the earth was trying to shake the concrete – or me – off itself.

Is this an earthquake?

My mouth opened to scream but no sound came out. Gasping, I looked down again. Like a twig snapping, the slab under my feet cracked clean in two. The crack gained momentum, ripping its way through the patio all the way from the tree to the back door. It broke the patio as easily as a warm knife slicing through butter, leaving behind a trail of smashed concrete.

The damage was worst by the tree. The concrete round its trunk had shattered outwards in a crude circle of fractured slabs. It looked like it was trying to smile through a mouthful of broken teeth. I saw something, stuck in the cracked slab under my feet.

And I couldn’t look away.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.