Kitabı oxu: «Borrowed Finery»

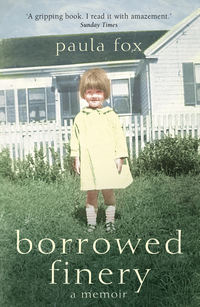

Borrowed

Finery

a memoir

Paula Fox

For my family, my husband, Martin Greenberg,

and for Sheila Gordon,

who sustained me throughout this work

with her endless patience and affection

“After so long grief, such nativity!”

—The Comedy of Errors

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Epigraph

BORROWED FINERY

Balmville

Hollywood

Long Island

Cuba

New York City

Florida

New Hampshire

New York City

Montréal

New York City

California

Elsie and Linda

About The Author

Praise

Also By Paula Fox

Copyright

About the Publisher

BORROWED FINERY

When I was seventeen, I found a job in what was then downtown Los Angeles in a store where dresses were sold for a dollar each. The store survived through its monthly going-out-of-business sales.

Every few days I was required to descend to the basement to bring up fresh stock to replace what had been sold. It was a vast space, barely lit by a weak bulb hanging from a low ceiling, and appeared to extend beyond the boundaries of the store itself. In its damp reaches I sometimes glimpsed a rat shuttling along a pipe, its naked tail like an earthworm.

Against one wall, piled up on roughly carpentered wood shelves, were flimsy boxes of dresses. In front of the opposite wall was an enormous cardboard cutout, at least ten feet high, of Santa Claus, his sled, and his reindeer. I guessed this was displayed in the store upstairs at Christmastime.

One morning when I was sent to the basement for dresses, I noticed drops of sweat on Santa’s brow. Later it occurred to me that the pipe along which I’d seen rats running extended over the cutout, and leaks could account for the appearance of sweat. But at the time I imagined it was because of his outfit. He was as inappropriately dressed for the California climate as I was in my thick blue tweed suit.

I’ve long forgotten who gave the suit to me. I do recall it was a couple of sizes too big and sewn of such grimly durable wool that the jacket and skirt could have stood upright on the floor.

I earned scant pay at a number of jobs I found and lost that year, barely enough for rent and food with nothing to spare for clothes. What I owned in the way of a wardrobe could have fitted into the sort of suitcase now referred to in luggage ads as a “weekender,” a few scraps that would cover me but wouldn’t serve in extremes of weather—and, of course, the blue tweed suit that I wore to work in the Los Angeles dress store day after day.

In that time I understood mouse money but not cat money. Five dollars were real. I could stretch them so they would last. I was bewildered even by the thought of fifty dollars. How much was $50?

The actress ZaSu Pitts, in a publicity still—an advertisement for the movie Greed made in 1923, the year I was born, that showed her crouching half naked among heaps of gold coins, an expression of demented rapacity on her face—embodied my view of American capitalism when I was a young girl. As I grew older, my attitude about money changed. I began to see how complex it was, how some people accumulate it for its own sake, driven by forces as mysterious to me as those that drive termites to build mounds that attain heights of as much as forty feet in certain parts of the world.

At the same time that I began to acquire material things, my appetite for them was aroused. Yet in my mind’s eye, the image of ZaSu Pitts holding out handfuls of gold coins, not offering them but gloating over her possession of them, persists, an image both condemnatory and triumphant.

Balmville

The Reverend Elwood Amos Corning, the Congregational minister who took care of me in my infancy and earliest years and whom I called Uncle Elwood, always saw to it that I didn’t look down and out. Twice a year, in the spring and fall, he bought a few things for me to wear, spending what he could from the yearly salary paid to him by his church. Other clothes came my way donated by the mothers in his congregation whose own children had outgrown them. They were mended, washed, and ironed before they were handed on.

In early April, before my fifth birthday, my father mailed Uncle Elwood two five-dollar bills and a written note. I can see him reading the note as he holds it and the bills in one hand, while with the index finger of the other he presses the bridge of his eyeglasses against his nose because he has broken the sidepiece. This particularity of memory can be partly attributed to the rarity of my father’s notes—not to mention enclosures of money—or else to the new dress that part of the ten dollars paid for. Or so I imagine.

The next morning Uncle Elwood drove me in his old Packard from the Victorian house on the hill in Balmville, New York, where we lived, to Newburgh, a valley town half an hour distant and a dozen miles north of the Storm King promontory, which sinks into the Hudson River like an elephant’s brow.

We parked on Water Street in front of a barbershop where I was taken at intervals to have my hair cut. One morning after we had left the shop, and because I was lost in reverie, staring down at the sidewalk but not seeing it, I reached up to take Uncle Elwood’s hand and walked nearly a block before I realized I was holding the hand of a stranger. I let go and turned around and saw that everyone who was on the street was waiting to see how far I would go and what I would do when I looked up. Watching were both barbers from their shop doorway, Uncle Elwood with his hands clasped in front of him, three or four people on their way somewhere, and the stranger whose hand I had been holding. They were all smiling in anticipation of my surprise. For a moment the street was transformed into a familiar room in a beloved house. Still, I was faintly alarmed and ran back to Uncle Elwood.

Our destination that day was Schoonmaker’s department store, next to the barbershop. When we emerged back on the sidewalk, he was carrying a box that contained a white dotted-swiss dress. It had a Peter Pan collar and fell straight to its hem from a smocked yoke.

Uncle Elwood had written a poem for me to recite at the Easter service in the church where he preached. Now I would have something new to wear, something in which I could stand before the congregation and speak his words. I loved him, and I loved the dotted-swiss dress.

Years later, when I read through the few letters and notes my father had written to Uncle Elwood, and which he had saved, I realized how Daddy had played the coquette in his apologies for his remissness in supporting me. His excuses were made with a kind of fraudulent heartiness, as though he were boasting, not confessing. His handwriting, though, was beautiful, an orderly flight of birds across the yellowing pages.

Uncle Elwood made parish visits most Sundays in Washingtonville, at that time still small enough to be called a village, in Orange County, New York, seventeen miles from Balmville, where most members of his congregation lived. The church where he preached was in Blooming Grove, a hamlet a mile or so west of Washingtonville, on a high ridge above a narrow country lane, and so towering—it appeared to me—it could have been a massive white ship anchored there, except for its steeple, which rose toward the heavens like prayerful hands, palms pressed together.

Behind it stood an empty manse and, farther away, a small cemetery. To the right of the church portal was a partly collapsed stable with dark cobwebbed stalls, one of which was still used by a single parishioner, ancient bearded Mr. Howell, who drove his buckboard and horse up the gravel-covered road that led to the church. He always arrived a minute or two before Sunday service began, dressed in a threadbare black overcoat in all seasons of the year, its collar held tight to his throat by a big safety pin. He seemed to me that rock of ages we sang about in the hymn.

After the service, we sometimes called upon two women, an elderly woman and her unmarried daughter, who looked as old as her mother, both in the church choir, whose thin soprano quavers continued long past the moment when other choir members had ceased to sing and had resumed their seats. They appeared not to notice they were the only people still standing in the choir stall.

They lived in a narrow wooden two-story house that resembled most of the other houses in Washingtonville. They would give us Sunday dinner in a back room that ran the width of the house and could accommodate a table large enough for the four of us. It was a distance from the kitchen, where they usually ate their meals, and there was much to-ing and fro-ing as they brought dishes and took them away, adding, it felt to me, years of waiting to the minutes when we actually ate. Summer heat bore down on that back room. It was stifling, hot as burning kindling under the noonday sun. Everything flashed and glittered—cutlery, water glasses, window panes—and drained the food of color.

When we visited Emma Board and her family in another part of the village, I felt a kind of happiness and, at the same time, an apprehension—like that of a traveler who returns to a country where she has endured inexplicable suffering.

I had arrived at the Boards’ house when I was two months old, brought there by Katherine, the eldest of four Board children. She had taken me to Virginia on her brief honeymoon with Russell, her new husband. When they returned, her mother was sufficiently recovered from Spanish influenza to take care of an infant.

I heard the tale decades later from Brewster, one of Katherine’s two brothers, who had lived in New York City with Leopold, one of my mother’s four brothers. I had been left in a Manhattan foundling home a few days after my birth by my reluctant father, and by Elsie, my mother, panic-stricken and ungovernable in her haste to have done with me.

My grandmother, Candelaria, during a brief visit to New York City from Cuba, where she lived on a sugar plantation most of the year, inquired of Leopold the whereabouts of his sister and the baby she knew had been born a few weeks earlier. He said he didn’t know where my parents had gone, but that over his objections they had placed me in a foundling home before leaving town—if indeed they had left.

When she heard where I was, my grandmother went at once to the home and took me away. But what could she do with me? She was obliged to return to Cuba within days. For a small monthly stipend, she served as companion to a rich old cousin, the plantation owner, who was subject to fits of lunacy.

It was Brewster who suggested she hand me over to Katherine, who carried me in her arms on her bridal journey to Norfolk.

By chance, by good fortune, I had landed in the hands of rescuers, a fire brigade that passed me along from person to person until I was safe. When we visited the old woman and her daughter, or any other of the minister’s parishioners, I was diffident and self-conscious for the first few minutes. But not ever at the Boards’.

For a very short period of my infancy, I had belonged in that house with that family. At some moment during our visits there, I would go down the cellar steps and see if a brown rattan baby buggy and a creaking old crib, used at one time or another by all the Board children and for three months by me, were still stored there. I think the family kept them so I would always find them.

I was five months old when the minister, hearing of my presence in Washingtonville and the singular way I had arrived, an event that had ruffled the nearly motionless, pond-like surface of village life—and knowing the uncertainty of my future, for the Boards, like most of their neighbors in those years, were poor—came by one Sunday to look at me. I was awake in the crib. I might have smiled up at him. In any event, I aroused his interest and compassion. He offered to take me, and, partly due to their straitened circumstances, the Boards agreed to let me go.

After he finished his sermon, Uncle Elwood would step aside from the pulpit. As the choir rose to sing, he would clasp his hands and gaze down at me where I sat alone in a front pew. There would be the barest suggestion of a smile on his face, a lightening of his Sunday look of solemnity.

The intimacy of those moments between us would give way when a church deacon passed a collection plate among the congregation, now hushed by an upwelling sense of the sacred that followed a reading of Bible verse. When he reached my pew, I would drop in a coin given me earlier by Uncle Elwood.

Later, when I stood beside him at the church portal while people filed out and shook his hand, and old Mr. Howell hurried by, mumbling his thanks for the sermon in a rusty, hollow voice, the feeling of intimacy returned.

I was known to the congregation as the minister’s little girl, and thinking of that, I was always gladdened. I turned to him after Mr. Howell had vanished into the stable, noting as I usually did the formality of his preaching clothes, the pearl stickpin in his black and silver tie, a silken stripe running down the side of the black trousers, the beetle-winged tails of his black jacket.

It was like the Sunday a week earlier, and all the Sundays I could recall. I slipped my hand into his, and he clasped it firmly. I watched Mr. Howell, who had backed his buckboard and horse out of the stable and was starting down the road.

My unquestioning trust in Uncle Elwood’s love, and in the refuge he had provided for me in the years since Katherine had taken me to her mother, would abruptly collapse. In an instant, I realized the precariousness of my circumstances. I felt the earth crumble beneath my feet. I tottered on the edge of an abyss. If I fell, I knew I would fall forever.

That happened too every Sunday after church. But it lasted no longer than it takes to describe it.

Great storms swept down the Hudson Valley in the summer, especially in August. Thunder and lightning boomed and crackled. The world around the house in Balmville flashed with gusts of wind-driven rain. Through black dissolving windows, trees swayed and bent as they appeared to move closer, to form a circle of leaves and agitated branches that threatened to swallow up the house and us with it.

When the storms struck late at night, Uncle Elwood first woke me—if thunder hadn’t already—and then went to his mother’s room. He lifted her up from her bed and carried her past the large pier glass at the top of the stairs, and together we went down to the central hall, where he settled her in an armchair he would have moved from the living room earlier that day when he had first noticed black clouds forming in the sky.

Emily Corning had been crippled with arthritis for eighteen years, and she bore the pain of it with patience and austerity as though it were a hard task imposed on her to test her faith in the deity.

In the flickering yellow glow of the kerosene lamp the minister kept for such emergencies—the electricity always failed during storms—I would stare at the old woman sitting in the shadowed corner, not quite covered by a shawl her son had wrapped around her. A mild smile would touch her colorless lips when she grew aware of my scrutiny. She was unable to lift her head upright and peered at everyone from beneath her brow. She rarely spoke to me, yet I could feel kindness emanating from her just as I could feel the distant warmth of the sun in winter. Her words were few and nearly always about the view of the Hudson River, which she could see from her wheelchair, placed by the minister in front of the three-windowed bay in her bedroom all the mornings that I lived in that house.

Often at night, rarely during the day, and only when she was in terrible pain, I could hear through the closed doors between our bedrooms her gasps for breath, her faint cries, and Uncle Elwood’s efforts to comfort her. I would lie rigidly beneath the rose-colored blanket in my bed, imploring God to end what seemed endless, to let her fall asleep.

Sometimes when the thunder had diminished and only rumbled distantly, the minister would light a candle and carry his mother into the living room so she could see the dark wallpaper with its pattern of pussy-willow branches in bloom. She had chosen it decades earlier, when her husband was still living and she had been able to move freely about the house.

At an unexpected clap of thunder nearby, he would bring her back into the hall and return her to her chair, settling her into it as if she were a doll.

He told me with a humorous emphasis in his voice, so I would know not to believe him, that Henry Hudson and his crew were bowling somewhere up the river. But I half believed it.

When the minister’s only sister was visiting, and a fierce storm rumbled down the river and blew out the lights, she too sat with us in the downstairs hall, crocheting by lamp-light, her face with its pouchy cheeks bent over her work. She asked me to call her “Auntie,” which I did as seldom as possible.

As the pealing of the thunder weakened, the old woman and her daughter dozed. Their faces in repose looked sad, as if they had fallen asleep worn out by mourning a loss. Perhaps it was only a trick of the shadows.

I fell asleep too. Uncle Elwood carried me to my bedroom. As he drew up the blanket to cover me, I awoke and saw through my window the lights of Mattewan, a madhouse across the river, glittering among the leaves and branches that struck the panes fiercely as the wind blew.

Auntie had a married daughter who lived in Massachusetts. As far as I knew, she divided her time between that household and ours.

In winter, she regretted ceaselessly and aloud that the heat of the furnace, sent up through dusty registers in the floors of the living room and dining room, didn’t reach the bedrooms; in summer, that I made such a dreadful racket running up and down the stairs on my way in or out of the house it gave her headaches—why wasn’t there a rug to cover the landing?—and that the meals her brother fixed were skimpy and lacked variety—couldn’t he hire a woman on a regular basis to cook and clean, instead of the patchy arrangements with Mrs. So-and-So down the road?

She complained to her brother, when I was within hearing distance, that he gave too much time to certain parishioners of his church—whose services she attended rigorously, a baleful presence among the congregation.

Her voice was often shattered by fits of coughing. She smoked cigarettes, somewhat furtively, and carried a pack of them in a cloth bag, along with scraps of cotton or wool with which she rapidly crocheted small rugs and blankets in colors that suggested mud or blood or urine.

The cloth bag had a wooden handle and was embroidered with a design that made me uneasy. Perhaps it was the reddish entwined loops that led me to think of the copperhead snakes Uncle Elwood had warned me about, lurking in the woods in spring.

Auntie spent most afternoons murmuring to her mother, leaning over in a chair drawn so close to the wheelchair I thought she might topple over. She appeared to be about to creep into the old woman’s lap.

But the way she sat was not a posture of intimacy, I think now, or of childlike dependence. Even then I sensed there was resentment in the way she thrust her body at her mother, as though the older woman were still responsible for its miseries.

Could she be telling the story of her divorce over and over again? Uncle Elwood said that she and her husband no longer lived together. They had been divorced. Such an event had never before occurred in the family.

He looked startled as he spoke of it, as though the news had just reached him, although by the time he told me about it, it was old news. Could you escape from a divorce the way you could from a marriage? Was it possible to get a divorce from a divorce?

When the old woman’s windows were open and a breeze blew through the room, it wafted Auntie’s particular odor toward the doorway where I had paused on my way somewhere—a disagreeable smell composed of tobacco, mothballs, and the cough drops she sucked between cigarettes.

If she wasn’t crocheting or whispering to her mother, she followed me about the house, wheedling and hectoring by turns. She was the peevish serpent in the short-lived Eden of my childhood.

There was a three-legged stool in old Mrs. Corning’s bedroom that I sometimes moved from its usual place in a corner to her wheelchair and sat on, close to her motionless legs.

Earlier in the day, the minister would have lifted her to a sitting position on the edge of her bed, carried her to the bathroom, placed her on the toilet, waited outside the door until she signaled she was through, brought her back to her room, dressed her in one of her three or four print dresses, and carried her to the wheelchair in front of the bay windows, where she would spend the day until early evening, when he would carry her back to her bed.

She wore soft wool slippers.

She was as unmoving as a woman in a painting. When the day was fine, the sky unclouded, one of those blue American days full of buoyancy and promise that seemed to occur only when I was small, she might break the tranquil silence between us with a remark about the river. How beautiful it always was, she might comment, in her rather toneless voice. She could see Polpis Island and glimpse a bit of West Point just beyond the Storm King mountain. Then she would slip back into silence as though resuming a dream.

Uncle Elwood told me she had been a widow for many years. The dream might have been about her husband, how she had stood with him on the deck of a steamboat, northbound on the Hudson River, and he had seen the land that he would purchase months later to build a house on for her, this very house where she still lived, an old woman confined by illness to a wheelchair.

I looked at her hands, which lay on the wood tray fitted between the chair’s arms. They were so twisted they looked like small knobbed claws pointing at each other.

Very slowly, she bowed her head even farther down and smiled at me. It was an impersonal smile, as if pain had worn away any distinctive traits that might have defined her nature. As I looked up at the slight widening of her mouth, I imagined I recognized a kind of incorporeal kindness—and I think for those few minutes she was able to stand apart from her wounded body.

I couldn’t conceive of Uncle Elwood’s struggle to make do with the yearly salary he was paid by the church so that it would take care of his mother, himself, and me, along with paying for repairs to the ailing house, any more than I could have conceived of the lives of my parents unfolding somewhere in the world. And I would not have known how poor the Blooming Grove parishioners were, how they could barely afford a pastor of their own.

Behind his mother’s closed door, I could hear him telling her, in a voice made loud and incautious by desperation, that he had to replace the coal furnace—which he had to stoke every evening and morning when the weather turned cold—with an oil burner and that the house required a new roof. It leaked so shockingly, he said, he could fly to Jericho!

At his words, fly to Jericho, my heart jumped into my throat. It was the most extreme thing I ever heard him utter. He was at the end of his rope! It was the absolute limit!

His protests never lasted more than a few minutes, but the pictures that formed in my mind, evoked by the distress I heard in his voice—usually so serene, so playful—frightened me.

The malevolent furnace, as it labored at night with great clankings, would climb the stairs and kill us with fire, and the holes in the roof would be enlarged so drastically we would be exposed to the merciless night sky and its rain and wind and cold.

But more terrible by far was the well in the middle of the meadow.

When the water pressure in the house was so low that only a puff of stale air came from the kitchen faucet when it was turned on, and the toilet in the bathroom wouldn’t flush, Uncle Elwood set out for the well, carrying a bucket.

I watched in dread from the living room window as he lowered the bucket by a rope tied to his hand. He leaned far out over the edge of the well—too far!—to keep the rope straight as it dropped an instant later, to hit the water with a plonk.

He would fall! An enormous jet of well water would lift his drowned body toward the sky, then flood the whole earth!

He hauled on the rope, hand over hand, and at last pulled out the bucket, filled. When I ran out of the house and down the three broad steps of the porch to meet him, he was surprised at the intensity of my relief, as though he had returned safely from a long perilous journey.

Then he recalled what I had told him of my fear when he went to the well. He spoke reassuringly to me, as he did when I was ill. He told me what a fine artesian well it was, how milk snakes kept the water pure. Oh, snakes! Worse!

With his unengaged arm, he clasped me to his side as we walked across the hummocky ground. I was not able to explain to him the extremity of my terror. I couldn’t explain it to myself.

Time was long in those days, without measure. I marched through the mornings as if there were nothing behind me or in front of me, and all I carried, lightly, was the present, a moment without end.

From the living room there were views east and south. A line of maple trees and birches marked the southern boundary of the property, and beyond it stood an abandoned mansion. I had walked along its narrow porch among six towering columns and peered through dusty windows at its empty rooms. The ground sloped gently down to the river less than a mile away. It was the same long slope upon which our house stood.

From the windows that faced east, beyond the line of tall sumacs, rose a monastery whose roofs and towers I could see in late autumn and winter, when the deciduous trees surrounding it shed their leaves. At intervals during the day the monastery bells pealed.

When I sat on the porch in my wicker rocking chair in the twilight of a summer’s day, eating a supper of cold cereal and buttered bread, I would echo the sounds the bells made by tapping my spoon against the side of the china bowl that had held the cereal. I was alone with my thoughts. They drifted through my mind like clouds that change their shapes as you gaze up at them.

To the north where the storms came from, I could view from the windows in the minister’s study a line of tall, thick-trunked evergreen trees and, as though I were on a moving train, catch glimpses of a crumbling wall and some of its fallen stones lying on the pine-needle-strewn ground. Uncle Elwood said the wall had been there when his father bought the property.

Beyond the lawn, which he tended now and then, doggedly and with an air of restrained impatience, pushing a lawn mower with rusty blades, were meadows grown wild. Once or twice a year, a farmer driving a tractor, his wife and their children in a small ramshackle truck behind him, arrived to cut the tall grass and carry it away.

Once the children brought along a sickly puppy and showed it to me. We passed its limp body among us, caressed it, and at last killed it with love. We stared, stricken, at the tiny dog lying dead in the older boy’s hands, saliva foaming and dripping from its muzzle. The younger brother began to grin uneasily.

Later that day, after the farmer and his family had departed, I told the minister I had had a hand in the death of the little animal. Although he tried to comfort me, to give me some sort of absolution, I couldn’t accept it for many years.

Even now, I am haunted from time to time by the image of a small group of children, myself among them, standing silently at the back door of the house, looking down at the corpse.

Every spring, thawing snow and rain washed away soil from the surface of the long driveway, leaving deep muddy furrows and exposed stones. I spent hours cracking the stones open, using one for an anvil, another for a hammer, to find out what was inside them. Most appeared to be composed of the same gray matter, but a few revealed streaks of color and different textures in their depths or glinted with sparks of light.

I saw how Uncle Elwood struggled to hold the steering wheel of the car steady as it heaved and skidded along the rough, wet, torn-up ground. But I thought too of how gratifying it was when I found a stone that stood out from the rest because of what was inside it.

The driveway led up to scraggly, patchy lawn, circled the house, then branched off, ending several feet from the entrance to a cave-like, half-collapsed stable that had been built into the side of the slope. Earth nearly covered its roof.

During storms, the minister would race out to the car and drive it into the stable as far as it would go. Once a horse named Dandy Boy had lived in its one stall.

The minister told me stories that illustrated Dandy Boy’s high spirits and animal nobility. “He had moxie,” he said, and imitated a horse, galloping from the living room where I stood entranced, laughing, into the dining room just as Dandy Boy had galloped into the world.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.