Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Girl Most Likely To»

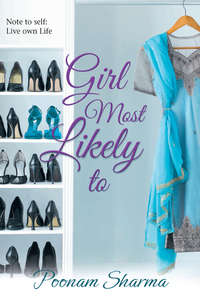

Girl Most Likely to

Poonam Sharma

Contents

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

My Postscript

Coming Next Month

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to…

My agent, Lorin Rees, for helping me

make the leap into fiction.

My editor, Kathryn Lye, who improves the story

without altering the point.

Red Dress Ink, for taking me on.

And my family—for their inspiration, humility,

and for being the sort of people who never give up,

nor fail to be grateful for it all.

For a guy named Michael, who knew me once,

and thought that I should write a novel.

1

“Celibacy is rotting your brain.”

Cristina insisted through my cell phone, while the taxi jerked up Fifth Avenue. It might even have been true, but it was a hateful thing for a best friend to say.

At my age—and my father never missed an opportunity to remind me of my age with all the subtlety of a presidential ass-pat—my mother had managed a screaming child, a barking dog, a doting husband and a medical residency. And she did it from a three-bedroom Colonial in Great Neck, Long Island. By twenty-seven, left to my own devices, I had amassed a lucrative, yet uninspiring, seventy-hour Wall Street workweek, a telling but unintentional track record of shoving plant corpses down the trash chute while the neighbors slept, and a very large, very expensive and very empty bed. It was the latter fact that had me feeling particularly vulnerable. And of the many mistakes I made that Saturday evening, the first was expecting Cristina to understand.

“Just because I’ve decided to be rational and take control of my life, that doesn’t mean I’m crazy.” I pouted, checking my watch. Draped in my traditional powder-blue silk salwar kameez and matching satin Charles David heels, I was hurtling helplessly toward another lavish Indian wedding where my parents would be seated where the love of my life ought to be. After ten years of scouring every dormitory bar, party and young singles’ mixer, not to mention checking under every rock and in more than my fair share of countries around the world, I was in no mood for honesty. If bunions were my reward for a decade of running in four-inch heels, then cynicism was my logical response to the umpteenth fix-up with a prince whose castle would eventually make me break out in hives.

“But an arranged marriage? For you, Vina?” her voice climbed. It was laced with all the straight-postured self-righteousness of a New England housewife snatching home hair dye from the hands of a teenaged daughter. “I don’t think so.”

I sucked air through clenched teeth.

“See? This is why I wasn’t going to tell you about tonight. And it’s not an arranged marriage. It’s an arranged…date, and it just happens to be taking place at a wedding.”

Ever since I met Cristina, when we were the lone female interns in the J.P. Morgan investment banking department, she’d refused to cut me emotional slack. And that was what I respected most about her. Unfortunately, she also refused to accept that merely being ethnic (Cuban, and from Miami) didn’t mean she automatically grasped my situation. Convincing her that it was a good idea to be set up with the Punjabi lawyer courtesy of my parents required an appeal to the rational side of her brain. Fortunately, we were both investment bankers; I knew exactly how to put things into terms that she could grasp.

“Look,” I added, cradling my cell between ear and shoulder while aiming my compact at the pinky finger I used to catch errant eyeliner, “I have thirty months left until thirty. I know your mom had you when she was, like, forty. But you have to understand that Indian women don’t have Cuban women’s genes. Sure, our hips were made for childbearing, but that’s where the similarity ends. The fact is that I’m only fertile until, like, thirty-five. And anyway, to figure out ideal fertility age, you take the average age of menopause for women in your family, and subtract twenty years. That’s when your fertility takes a serious nosedive. For my mom, menopause was fifty, so that means that childbirth is supposed to be before thirty for me.”

“But…”

“Also…consider that it takes at least six months to fall in love with anyone and run the required background checks, another nine months to get engaged, and a year to plan the wedding. And my husband and I will need at least a year of being married without being pregnant—to screw like bunnies before gravity has its way with me. That’s thirty-nine months. So even if I meet Mr. Right tonight, I’m still cutting it close.”

“Where do you get this stuff?”

My logic impressed her.

“They re-air The Oprah Winfrey Show at two a.m.” I clicked my compact shut, and noticed that one of my heels was stuck in a glob of gum on the floor of the cab. “And you know that I haven’t been sleeping well these days.”

In an effort to spare the hem of my salwar kameez, I leaned onto one hip and lifted my shoe. Naturally, the pleather seat beneath me mimicked a fart. My eyes collided in the rearview mirror with those of the cabbie, who, until that point, had occasionally glanced at me with the standard balance of boredom and curiosity. Suddenly he sat up straighter, spearing me with a look of moral superiority—all this from a man who had never encountered a stick of deodorant. I stared out the window.

“What kind of a name is Prakash, anyway?” Cristina finally asked.

“Um, I don’t know…an Indian one?”

“Well, it’s just not the kind of name that I can imagine you screaming out in a fit of passion.”

“Life is not a fit of passion, Cristy.” I resented her for making me sound like my mother. “And I think the point is that I’m supposed to have learned that by now. Look at it this way. Meeting a guy through my parents means that the background check is out of the way. Up front, I know that he’s single, educated and family-oriented, with no criminal record or illegitimate children.”

“And what if he looks like a frog?”

“He will not look like a frog.”

“But, Vina, what if he does? What if he looks like a bloated, slimy frog…who got hit in the face with a frying pan…twice?”

“Then I guess I’ll have to comfort myself with the thought of his really long—”

“Vina, I’m being serious! Have you thought this through? How much are you willing to compromise? Meeting a guy through your parents is a lot more serious than meeting him by yourself. It can’t be casual. You’ve always told me that.”

“All I know is that there are men that you date, and men that you marry.” I reached into my wallet for a twenty as we turned east onto Forty-seventh Street.

“And never the twain shall meet?”

I paused. “Did you just say ‘twain’?”

“Sorry. I’m feeling silly. I have a date with the cowboy tonight. Maybe I’m subconsciously practicing country phrases to put him at ease.”

“All Midwesterners are not cowboys, Cristy.” I signaled the cabbie for eight dollars in change.

“Yes, but this one is. Seriously. He has the cowboy hat and everything. He even grew up on a ranch.”

“And what…he took a wrong turn at the Old Oak Tree and wound up in New York City?”

“Apparently. And he must have asked someone to point him toward the nearest watering hole, because I met him at Denial, a bar over on Grand Street.”

“That is silly.” I wrenched the crumpled dollar bills from the plastic, swiveling slot, and smoothed them into a pile. Then I folded them and slipped them into my purse.

“Come on! Why don’t you ditch the wedding, and meet up with us instead? I’ll have him bring a fre-end,” she practically sang, as if she were dangling a new doll before my eyes.

“As tempted as I am by the idea of playing Cowboys and Indians twenty years after recess is over, I think I’ll pass.”

“Oh, I get it. When you play with firemen it’s perfectly acceptable, but when I try to throw a little rodeo it’s silly?”

I fought off a mental image of The Village People performing “YMCA,” and feigned indignation at Cristina. “I thought we agreed never to speak of that again.”

She followed suit. “We agreed on no such thing.”

“I was young.” I checked my watch for the tenth time since Union Square. “It’s a part of my past.”

“It was last year.” She paused, probably for dramatic effect. “And I believe the exact line that you used on that guy was ‘If I promise to run home and start a fire, will you promise to come over later?’”

“You gave me that line.” I cracked a smile. “Good times, though.” And then we giggled together, like only two women who know that they will see each other from virginity to Viagra can.

“Vina, I just don’t want you settling for some guy who isn’t your ‘Prince.’” Cristina took a typically cheap shot at our friend Pamela, who wasn’t there to defend herself. “You’ve been way too preoccupied lately with your so-called future.”

“Oh, who are you kidding, Cristina? I’m an Indian chick from Strong Island. I was born preoccupied with my so-called future.”

“I’m not talking about your professional future. I’m talking about your personal future. It’s like you’re turning into, well, I hate to say it, but…Pam.”

“Now that’s mean,” I said. “First, you make me feel more pathetic than I already do by reminding me that I haven’t had sex in forever, and now you’re comparing me to her. And come to think of it, you wouldn’t give her any crap if she was being set up with a nice Jewish lawyer by her parents.”

“You know you don’t want to get me started on Pam.”

“Agreed.” I sighed as we slowed to a halt by the curb outside the Waldorf Astoria. A uniformed doorman sped over and reached toward the door handle. “In fact, I don’t want to get you started on anything at the moment because my chariot has pulled up to the ball. Passionate Princes are a fairy tale, Cristy, but a Practical Prince will suit me fine.”

2

Red rose petals littered golden tablecloths. Gleaming china settings and generous floral arrangements adorned each table. The air was delicately scented. Votives flickered on every surface, fading in comparison to the luster of the many rubies, emeralds and diamonds gliding around the ballroom. Waiters circled the tables while craning their necks to scan the room of the three hundred guests; the servers were determined not to leave any glass unfilled, any mouth unstuffed or any whim unattended. Toddlers peeked from behind the saris of young mothers, while older women sought potential daughters-and sons-in-law. Elders leaned back in their chairs, appreciating how their familiar chai seemed sweeter, and their familiar aches seemed duller in the face of so much life.

By ten p.m., there was no sign of Prakash. I speared a soggy Rasgulla with my fork and lifted the cheese-patty toward my mouth, while glaring daggers across Table 21.

“Certainly I miss living with Mummy and Papa in Delhi,” Cousin Neha gushed at our tableful of captivated parents.

Nearly all of their Americanized children had run as amok as I—moving into Manhattan apartments alone, while refusing to acknowledge “thirty and single” as a hopeless disease.

“Those three years after college and before my marriage were wonderful, really,” Neha continued, “I used to enjoy myself, having dinner and going to the cinema with my friends on the weekends. But Stamford, Connecticut, is also quite nice, although it is a bit chilly for us. Vinny and I drive to work together each morning, and then we go to one of the local restaurants in the evening, if I don’t feel like cooking.”

Rather than nailing Neha between the eyes, the fiery daggers I was hurling instantly transformed into plastic cocktail swords before they could make it across the table. They kept bouncing off of her matrimonial shield, and collapsing into a heap on the dessert plate in front of her. From where my second martini and I were seated, it looked as if that heap was about to topple and bury the remains of my self-esteem. My first martini had vanished instantly after the third consecutive “Auntie” (any non-blood-related woman old enough to be my mother who hasn’t seen me since I was this tall) inquired, before asking about anything else, when I was getting married myself. As soon as he’s paroled, I thought about saying, or perhaps, Tuesday. But you’re not invited. You can just send a gift to my apartment. I’m registered at Frederick’s of Hollywood.

“Neha darling, tell me…Have you also met any nice young couples to socialize with?” another Auntie-type asked from my right. Why everyone was so interested in my cousin was as much of a mystery to me as how The Anna Nicole Smith Show survived while Once and Again was canceled.

“Oh, yes! We have met many friendly couples,” Neha beamed girlishly at her husband, Vineet, who slurped his chai and winked at me. The wink was a gesture of encouragement to persevere, despite my tragic state of spinster-hood. “But you know…there are also many single people in Stamford. There are even single girls from India. I honestly feel sorry for them, being in a different country, spending the whole day alone and then going home to an empty apartment. When I talk with them it seems like it really does not bother them at all. They work, they live on their own, and they don’t even have any interest in marriage. They don’t even want to talk about it. Imagine!”

A three-hundred-pound woman who lives in the middle of nowhere, and has no friends outside of her husband, feeling sorry for me, I mocked telepathically to Marty—I had decided to name my martini by that point, as a reward for all of its loyalty. Imagine!

The same Auntie leaned over and practically yelled into my ear: “And what about you, Vina? Koi nehy milha?” She must have been speaking up to steal my attention from the many voices everybody assumed were living inside my head. These were, of course, the same voices that entertained all single career women when they came home to empty apartments at the end of each day. But I wondered why she also felt the need to shake a hand before her face like a tambourine. Were her fluttering fingers intended to deflect my bad romantic luck before it could infect any of the happy couples in the room? Great. I shook my head at Marty. Now they think I’ve become so hopeless that I require an emotional exorcist.

The bride and groom swirled past us on the dance floor. Twenty-seven-year-old Nikhil and Suraya, an MIT engineer and an NYU medical resident, had met at a friend’s dinner party the summer before. I spotted a number of single career women hiding behind ice sculptures just to avoid answering the same question posed at weddings the world over. I wondered if there was ever an appropriate response to koi nehy milha? Did I get anyone yet? Factually, it sounded hopeless. No, I have not. The truth sounded sluttish. Actually, I’ve had a few men. Even some I would recommend to a friend. But nobody with whom I’m interested in growing old and less attractive.

I chose to hide behind the facade of nonchalance familiar to all unattached Indian women of “marriageable age.” What that means is that I lied. “Oh, Auntie, I don’t have time to worry about that right now. I’m too passionate about my career.”

“Vina is just being shy,” my father interrupted. That man could never be accused of appropriate timing. “We are confident that tonight will be the night. We have found her a lovely boy.”

“Oh? Is this the doctor from Pittsburgh? The one you were telling me about?” Auntie Meenakshi questioned my mother hopefully. What doctor? Did she say Pittsburgh? Howmany other people were my parents discussing my personal life with?

“No, no.” My father shook his head. “We found out that the family in Pittsburgh had a history of divorces. This boy, Prakash, is thirty years old, which is suitable for Vina. He was born in New Jersey, but he lives in Manhattan now. He is an attorney, with a very impressive bio data. He is five feet eleven inches, and both his parents are engineers. We are disappointed that they are not Punjabi—they are Gujarati—but one has got to be open-minded on that point these days. And his father attended IIT in the same batch with the brother-in-law of my third cousin, Prem, who is now settled in Bombay. Everybody agrees that it is a good family. Prakash is the eldest of three brothers, and all are highly educated.”

Table 21 nodded in collective approval. “Lady in Red” wafted through the air. I drained the last of my martini, and checked for emergency exits.

“Why is everybody talking about this?” my maternal grandmother (referred to traditionally as Nani) interrupted in Hindi. “We have done our part. Now we must let the kids decide. And where is this Prakash, anyway? What kind of a boy would keep my Vina waiting?”

My earliest memory is of my Nani making Gulab Jamuns in our kitchen; I watched as she deep-fried and drizzled them with golden sugar water. I must have been six years old when I dragged that stool stoveside, and quietly climbed on top. Elbows on the counter, I waited silently until she tore off a piece of raw, sweet dough, and handed it to me. I never understood how she managed to grab the right amount of dough each time, and roll it so quickly into a perfect ball between her palms. And I asked her about my grandfather, whom I had never met.

“Your grandfather was a very good man.” She shook her head and reached for more dough. “Ithna shareef! Here they would have called him genuine, but he was much more than that. He cared for everybody. And he used to give your mother airplane rides on his shoulders. She was too small then to remember, even smaller than you are now.”

“Did he like Gulab Jamuns?” I swung my heels, chewing happily on the dough.

“He was a Gulab Jamun, daughter.” She stopped and looked at me. “He was my Gulab Jamun.”

“Did he look like a Gulab Jamun?” I leaned my head to one side.

“He did to me. And one day, your Gulab Jamun will come to you.” She caught my chin between her fingers.

“How will I know it’s him?”

“You will know,” she reassured me, before rolling a dozen balls into boiling oil, which refrained from splattering, under her watchful eye.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“But what if he looks more like a Jalebi?”

“He won’t.”

“What about a Rasgulla?”

“A Rasgulla looks nothing like a Gulab Jamun. Besides, mommy and daddy will recognize him and they will bring him for you when it is time.”

I paused, tilting my head. “But how will they recognize a Gulab Jamun if he looks like a Rasgulla or a Jalebi?”

She stopped, and eyed me. “You need not worry about such things, Vina. Good girls trust their parents. That is all you need to know.”

With that, I had to be satisfied. My Nani was always right.

“Ma’am? Another Rasgulla?” A waiter appeared. “Ma’am?”

“Vina? Are you paying attention?” my mother asked. Everybody at the table was staring at me. Maybe celibacy was rotting my brain.

“Don’t worry, little cousin.” Neha patted my shoulder before squeezing between the chairs on her way to the dance floor. “You’ll find someone soon.”

I’m not worried, I agreed with Marty. What I am is thirsty.

I scrunched my nose at the chai-bearing waiter leaning over my left shoulder. “I think I’m in the mood for something a little stronger.”

I pushed back my chair, rose to my feet and made a beeline for the bar.

In my defense, I arrived at the wedding feeling nothing less-than-thrilled for Suraya and Nikhil. I raised my f lute, alongside everyone else, in a toast to the newlyweds. I smiled through hours of idle chatter, and now I made my way rather steadily over to the bar. And that was where, as the twenty-one-year-old bartender started looking a little too good to me, it happened. I was reaching out to take hold of my third martini when I felt a warm hand crashing into my own.

My first instinct was to yank at the drink. Snatch it away and hold it above my head. To gulp it down and Take Back the Night. But I paused when I noticed that the very masculine hand was attached to a confident and sturdy arm, which had brought along an alarmingly attractive head. And the man to whom that head belonged seemed to be thinking the same about me.

“Bartender, I believe I asked for this to be shaken, not stirred,” he announced for my benefit.

Oooph, he’s yummy, I thought. If it meant being closer to a smile like that, I might actually consider climbing inside the martini. He was a cross between James Dean and Sunil Dutt (the James Dean of Indian cinema). I smiled and loosened my grip. Countless witty responses raced about inside my head, apparently bumping into one another enough to cause a massive concussion.

“Mmmhhhaaaahhaaahh,” I said. Or snorted. He must have assumed this was my own personal dialect, because he smiled as if he was impressed. I cleared my throat while he replaced the glass on the bar.

“I’ll thumb-wrestle you for it,” he said.

“Seriously?” I blurted. I was too tipsy to play anything cool in the face of such deep, mischievous eyes.

“No, not seriously.” He laughed, as if I were charming and had said it on purpose. Looking down, I noticed that our collision had splashed the martini across the sleeve of his tuxedo. Then I caught myself considering licking it off him. That was when I decided to cut myself off for the night. I must have reeked of mock-confidence and gin.

“I’m Prakash.” He wiped his hand on a napkin before extending one to me. “You must be Vina?”

Honey, I thought, I’ll be whoever you want me to be.

“Oh! Prakash!” I slapped my forehead, regretting it immediately. “Yes, my mother mentioned you. Well…it’s nice to finally meet you.”

Over Prakash’s shoulder I spotted my mother, who was watching us from across the room. She sat with her thumbs and eyebrows raised, as if she were rooting for the lone Indian on Fear Factor. I assumed that that was Prakash’s mother seated beside her, considering that the woman couldn’t resist a nod of satisfaction at the childbearing capacity that the fit of my salwar kameez made plain. With a full belly and an expectant heart, my father napped quietly in his chair, probably dreaming of telling his grandchildren to sit up straight.

The latest version of a classic Bhangra song, which had apparently been mixed with the theme from Knight Rider, trailed off, and “Careless Whisper” picked up. DJ Jazzy-Desi-Curry-Rupee, or whatever his name was, called out to the crowd, “Can we please haw all the luwly gentleman and lehdees join us on the danz floor now for a wery special slow song?”

Hands cupped behind his back, Prakash faked a nervous glance at the floor: “Your mom told my mom to tell me to ask you to dance. So…I mean…do you wanna?”

I grinned, and he led me toward the dance floor. Crowds dispersed. Couples embraced. Prakash took me into his arms. His frame was stiff enough to let me know who was leading, even as he refused to drop his playful gaze. We sailed around the floor, almost as captivatingly as the two five-year-olds who were probably forced out there by some photo-hungry parents nearby. I didn’t need a mirror to know how perfect Prakash and I looked together.

Imagine my luck, I thought. I’ve found an attorney, who’s adorable, and funny, and a good dancer…and Indian? Tomorrow I’ll start auditioning matrimonial henna tatoo artists. On Monday morning I’ll look into the logistics of renting the horse upon which Prakash will arrive at our wedding.

A lesser man might have dropped me at the pivotal moment, but Perfect Prakash held me firmly, as I leaned into his arm and kicked back my leg. He dipped me so far that the ends of my hair touched the floor. I smiled for my parents, as much as for myself, while all the blood rushed straight to my head.

“So, Prakash…you’re handsome, you’re charming, and you’re a lawyer,” I began once he had pulled me up. “How is it possible that no woman has snatched you off the market yet?”

“Vina, there’s a perfectly simple explanation for that,” he replied, watching my form more than my eyes as he spun me around, and twisted me like a Fruit Roll-Up into one arm.

“I’m as gay as they come!”

I unraveled. I think I would have preferred to have been dropped.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.