Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «All of These People: A Memoir»

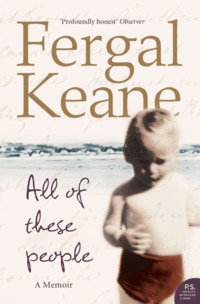

All of these people

A Memoir

Fergal Keane

For My Parents

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE Echoes

CHAPTER TWO Homeland

CHAPTER THREE The Kingdom

CHAPTER FOUR Tippler

CHAPTER FIVE Shelter

CHAPTER SIX ‘Pres’ Boy

CHAPTER SEVEN The junior

CHAPTER EIGHT Local Lessons

CHAPTER NINE Short Takes

CHAPTER TEN Into Africa

CHAPTER ELEVEN The Land That Happened Inside Us

CHAPTER TWELVE Cute Hoors

CHAPTER THIRTEEN North

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Marching Seasons

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Visitor

CHAPTER SIXTEEN A Journey Back

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Beloved Country

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN People Are People

CHAPTER NINETEEN Limits

CHAPTER TWENTY Valentina

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Witness

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Consequences

P.S.

About the author

From Our Own Correspondent

LIFE at a Glance

Top Ten Favourite Books

A Writer’s Life

About the book

In the Bone Shop of the Heart: Writing All of These People

Read on

Have You Read?

If You Loved This, You Might Like…

EPILOGUE A Last Battle

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Early in the new year, 2004, I was due to meet a friend for coffee in Chelsea. As I waited an elderly man entered and went to the front of the line. I felt a flash of annoyance and tried to attract the attention of the staff. ‘He’s jumping the queue,’ I said. But nobody heard me. The manager came and showed the man to a table. He turned, slowly, and I looked into the face of my father.

In the fourteen years since his death he had not changed.

My father did not recognise me but I knew him: those poetic lips, the melancholy vagueness of the old king fighting his last battle, the same shock of greying black hair, the thick-rimmed glasses, the tweed hat and scarf I gave him once for Christmas, the aquiline nose – the Keane nose! Crossing O’Connell Bridge in Dublin one day Paddy Kavanagh had turned to my father, his friend, and remarked: ‘Keane, you have a nose like the Romans but no empire to bring down with you!’

The man in the coffee shop was not, of course, really my father, but it was his face I saw. After being seated at a table near the window he had begun to talk to himself. I heard him. An English accent – upper class, not at all like my father’s. ‘I want to admire the magic,’ he said, and made a grand, kingly gesture, waving his hand. The manager laughed.

They both laughed. It was the kind of language Éamonn, my father, would have used. Expansive. I want to admire the magic…

This book began as an attempt to describe my journalistic life and the people and events which have shaped my consciousness. I had come through several traumatic personal experiences and arrived at middle age – a time when men often collide with their limitations and feel the first chill of mortality. I needed to take stock of where I had come from, examine the influences which had formed me, and to look at where I might be going. There were also certain resolutions to be made in the way I lived my life. Chiefly they concerned the risks I was taking in different conflict zones of the world.

What I did not understand then was that another imperative would emerge. This book would also become a journey in search of someone I had loved but with whose memory I was painfully unreconciled. When I tried to describe my journalistic life and world, I found my father waiting for me at every corner; the past intruded so acutely on the present that I found myself pulled constantly towards a man who had been dead for more than fourteen years. For much of my adult life I had lived in confusion about my father: thoughts of him made me feel both angry and sad. I could never understand him or the manner in which our relationship had affected my life.

When I look now at my journalism, at the preoccupations which have remained constant – human rights, the struggles for reconciliation in wounded lands, the impulse to find hope in the face of desolation – I know that I am largely defined by the experiences of childhood. Since much of that childhood was framed by the realities of growing up in a household dominated by my father’s alcoholism, it might be assumed that I found my father’s influence to be a wholly negative one. This book acknowledges the pain of the past, but writing it has revealed to me that both my parents gave me gifts that were profound and lasting. Their passionate natures and belief in justice were my formative inspiration. They were, above all, people of instinct. I doubt that either of them had a calculating bone in their bodies.

I did not always realise the good they had handed on; I too often saw the past through the prism of an angry, alienated child. But a personal crisis in the closing years of the last millennium set me on a journey towards understanding my father. I travelled part of his road of suffering and found that I was more like him than I knew.

Two physical landscapes dominate this book. One is the country in which I grew up and which, for all my exile’s tendency to criticise, I love and feel very proud of. I was a child of the Irish suburbs. The familiar worlds described in the conventional Irish narratives – misery in the tenements, a happy romp through the fields to school – were not mine. I was born of middle-class parents and grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s amid the death throes of traditional Catholic Ireland. I saw the emergence of a modern state at a time when one part of the island was descending into sectarian war and the other, my own country, was experiencing a social revolution unprecedented in its history.

The other landscape of this book is Africa, a place I loved from a distance as a child and which would draw me back again and again as an adult. Ireland and Africa are bound together for me. Events in Ireland have often helped me to make sense of what I saw in Africa, and my experiences in Africa, particularly in the age of apartheid, helped to illuminate possibilities of change in my homeland. I regard both as home in the larger sense of that word: they are places where I can feel a sense of belonging. In Africa I witnessed the death of people I knew. I saw friends taken away before their time. I saw the very worst of man and felt death brush my own shoulder. But I also met the best friend of my adult life, a man whose willingness to forgive was an inspiration.

Writing this book I have also tried to answer some fundamental questions: why was I willing to risk my life repeatedly? How did war change me? Why did I go to the zones of death? I have found that the motivations were as complex as the consequences. By the time I drove into Iraq during the war of 2004, a perilous drive from the Jordanian border to Baghdad, I had been a journalist for twenty-five years, fifteen of which had been spent reporting conflict.

I recently wrote down as many of these war zones as I could remember – Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Albania, Burundi, Congo, Cambodia, Colombia, Eritrea, Gaza, Northern Ireland, Sudan, Philippines, Rwanda, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Lebanon…all places where circumstances had reduced the daily lives of men and women to misery. I found that as I travelled the zones of conflict there was much that seemed familiar, echoes of the history of my own country. As a boy in primary school I had listened to legends and half-truths. I had heard the stories of an Irish war handed down by former combatants in my family. I was conscious too of the stories we were not told – of civil war and atrocity, the lies of silence used by our leaders to bury the past. Those echoes became louder as I wrote this book.

I have been well rewarded for my travels. My reporting of war has won plaudits, awards, public attention. Yet I found the longer I stayed on the road the more I became aware of the psychological backwash of war. This, of course, touched the participants and victims most of all, but for the professional witnesses there was also a high price to be paid, not mitigated by the fact that we had chosen to put ourselves in the line of fire.

For me the greatest consequence of life at war, particularly after the Rwandan genocide of 1994, was a feeling of guilt. The cataclysm which engulfed the Great Lakes region of Africa in the late spring of 1994 left many of the witnesses with lasting feelings of responsibility, or in some cases a rumbling but impotent rage. Sometimes you could experience all those feelings within seconds of each other. We had watched the unimaginable – the slaughter of nearly a million people in one hundred days – and we had survived. All of my friends who covered Rwanda came away with something more than memories: we were, in different ways and with varying degrees of intensity, haunted. In my case the story followed me for a decade. It follows me still. Rwanda led me into two extraordinary relationships: one an encounter of love, the other a confrontation with a man whom I felt myself loathing and fearing, and who in the end I would have to face in a courtroom in the middle of Africa.

While writing this book I have been surprised by the number of times I laughed at the recollection of this or that event and how inspired I have felt at the memory of certain individuals. Even in the worst of situations there have been kind gestures, compassionate acts; often these kindnesses have come from those who have been most abused, people who insisted, when we met, on recognising our shared humanity.

The title of this book, All of These People, comes from a poem by the Ulster writer, Michael Longley, one of the most sensitive chroniclers of the pain caused by the Troubles. It is his tribute to those who have inspired him; I carry a little photocopy of this poem wherever I travel in the world.

All of these people, alive or dead, are civilised.

The civilised are those who can love, forgive and hope. The world is full of them. My mother was one such person. My father too.

In this account there are individuals whom I have left out, either because they would not wish to be included, or because doing so might put them in the way of harm. In describing the relationship with my father, I am conscious that it is only my version of events, my direct conversation with somebody who is long gone but whose presence remains a constant in my life. Others will see him differently and remember different things about him.

I hope that anyone reading this book will come away from it with a sense of optimism. I am an optimist. I believe there is more good in humanity than evil, and that we are capable of changing for the better. This is the continuing lesson of my personal life as much as the public sphere in which I have operated. I make my claim on the entirely unscientific basis of one man’s lived experience: it is the view from the long journey, not blind to the madness but awake to our finer possibilities.

CHAPTER ONE Echoes

Ideal and beloved voices Of those who are dead, or of those who are lost to us like dead.

Sometimes they speak to us in our dreams; sometimes in thought the mind hears them.

And for a moment with their echo other echoes return from the first poetry of our lives – the music that extinguishes far-off night.

‘Voices’, C. P. CAVAFY

Here is a memory. It is winter, I think, some time in my seventh or eighth year. There is a fire burning in the grate. Bright orange flames are leaping up the chimney. The noise hisses, crackles. On the mantelpiece is a photograph of Roger Casement gazing at us with dark, sad eyes. My father loved Casement. An Irish protestant who gave his life for Ireland. In this memory my father sits in one chair; my mother is opposite him. They are rehearsing a play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by a man called Tom Stoppard. It will open at the Gate Theatre in Dublin in a few weeks’ time. I hear my parents’ voices going back and forth. My father’s voice is rich, deep. It rolls around the room, fills me up with wonder. My mother’s is softer, but so intense, the way she picks up when he stops. Never before have I seen such concentration, such fidelity to a moment. I don’t really understand this play. Two men are sent to kill another man. It’s about Hamlet, my mother explains. The two men are in the Shakespeare play. But who is Hamlet? It doesn’t matter. I am enchanted. I feel like part of some secret cell. I don’t want them to stop. I want this to last forever. Us being together in this calm; the words going on, softly, endlessly. Years and years later I try to find his voice, her voice, as they were on that night, when there was calm. If I will it hard enough I can hear them. My parents, the sinew and spirit of me.

My mother is pretty. She smells of Imperial Leather. Her hair is brown – long, and she asks me to comb it. Six pence for ten minutes. Half a crown for twenty. My father is darker and in the sun his skin tans quickly. Like a Spaniard. He says the Keanes are descended from Spanish sailors who were wrecked off the west coast of Ireland during the Spanish Armada. Such pictures he paints of our imagined beginnings along the rocky coast of Galicia, the great crossing of Biscay, the galleons smashed on the black rocks of Clare, the soldiers weighed down by their armour, sucked down into the cold. ‘Only the toughest survived,’he says.

His eyes are green like mine: ‘Like the heather,’ he says. When he poses for a publicity photograph for one of his productions my father looks like a romantic poet, a man who would sacrifice everything for his art. He wore a green tweed jacket; I remember the scratch of it when he embraced me. And the smell of John Players cigarettes, the ones in the little green boxes with the sailor’s head on the front, and I remember how the smoke would curl above his head. Sometimes in the mornings I would see him stooped over the bathroom sink in his vest, peering into a small mirror as he shaved. Afterwards he would have little strips of paper garlanded across his face to cover the tiny razor cuts. He used to tell a joke about that:

A rural parish priest goes into the barber’s and asks for a shave. The barber is fond of the drink and crippled with a hangover. His hands are shaking. Soon the priest’s face is covered in tiny little cuts.

Exasperated, he says to the barber: ‘The drink is an awful thing, Michael!’

The barber takes a second before replying.

‘You’re right about that, Father. ‘Tis awful. Sure the drink, Father…it makes the skin awful soft.’

I have a cottage by the sea on the south-east coast of Ireland. Every year I go there in August, the same month that I have been going there for over forty years. I am well aware that my addiction to this place is a form of shadow chasing. It was here, on the most restful of Irish coasts, that I enjoyed my happiest hours of childhood. What else are you doing, going back again and again, but foraging for the ghosts of lost summers?

Last August I went to a party at the house of a friend overlooking Ardmore Bay. We had sun that day and the horizon was clear for miles. In Ireland when I meet older people, they will frequently ask one of two questions: ‘Are you anything to John B. Keane?’ or ‘Are you Éamonn Keane’s son?’ Yes, a nephew. Yes, a son. My father and his brother were famous and well-loved figures in Ireland. Éamonn, the actor, and John B, the playwright. Although they are both dead, they are still revered. In Cork city people will usually ask if I am Maura Hassett’s boy: ‘Yes I am, her eldest.’ They will say they remember her, perhaps at university or acting in a play at one of the local theatres. ‘She was marvellous in that play about Rimbaud and Verlaine.’

At the party in Ardmore I was introduced to an elderly man, an artist, who had known my parents when they first met. In those days he was a set designer in the theatre. My parents were acting in the premiere of one of my uncle’s plays, Sharon’s Grave, about a tormented man hungry for land and love: ‘I have no legs to be travelling the country with. I must have my own place. I do be crying and cursing myself at night in bed because no woman will talk to me,’ he says. He is physically and emotionally crippled, a metaphor for the Ireland of the 1950s.

Stunted and isolated, Ireland sat on the western edge of Europe, blighted by poverty, still in thrall to the memory of its founding martyrs, a country of marginal farms, depressed cities and frustrated longings, with the great brooding presence of the Catholic Church lecturing and chiding its flock. My parents were children of this country, but they chafed against it remorselessly. The artist told me that he’d sketched them both during the rehearsals for the play.

‘What were they like?’ I asked him.

“The drawings? They were very ordinary,’ he replied.

I said I hadn’t meant the drawings. What had my parents been like?

‘Well, you could tell from early on they were an item,’ he said.

We chatted about his memories of them both. He praised them as actors, and talked about the excitement their romance had caused in Cork. The love affair between the two young actors became the talk of Cork city. The newspapers called it, predictably, a ‘whirlwind romance’. The news was leaked to the papers by the theatre company. Éamonn and Maura married after the briefest courtship. The love affair caught the imagination of literary Ireland. For their wedding the poet Brendan Kennelly gave them a present of a china plate decorated with images of Napoleon on his retreat from Moscow, and there were messages of congratulation from the likes of Brendan Behan and Patrick Kavanagh, both friends of my father. When the happy couple emerged smiling from Ballyphehane church, members of the theatre company lined up to cheer them, along with a guard of honour made up of girls from the school where my mother taught.

Once married they took to the road with the theatre company with Sharon’s Grave playing to enthusiastic houses across the country. In a boarding house somewhere in Ireland, a few hours after the last curtain call, I was conceived.

Several weeks after I met the artist who sketched my parents a brown parcel arrived at my home in London. Inside were two small photographs of his drawings. They looked so beautiful, my parents. My father handsome, a poet’s face; my mother, with flowing brown hair and melancholy eyes. Looking at those pictures I remembered a line I’d read somewhere about Modigliani and Akhmatova meeting in Paris: Both of them as yet untouched by their futures. The artist had caught them at a moment in their lives when they believed anything was possible. There is a poem by Raymond Carver where he remembers his own wedding. This remembrance comes after years of desolation, amid the collapse of his marriage.

And if anybody had come then with tidings of the future they would have been scourged from the gate nobody would have believed.

That was my parents in the year they met, 1960. I was the eldest of their three children, born less than twelve months after they were married and we would live together as a family for another eleven years.

I showed the sketched images of my parents to my eight-year-old son. He looked at them briefly and then wandered off to play some electronic game. I felt the urge to call him back, to demand that he sit down and contemplate the faces of his grandparents. But then, I thought, why would he want to at eight years of age? To him the past has not yet flowered into mystery. Anyway, he knows his grandmother well. Maura is a big figure in his life. He never met his grandfather whose gift for mischief he shares, and whose acting talent has already come down along the magic ladder of the genes.

He is occasionally curious though. ‘What was your dad like?’ he asks. ‘My dad and your granddad,’ I always say. Usually a few general words suffice, before his mind has hopped to something else. But I am sure the question will return when he is older. Just as I ask my mother about her parents, and wish I could have asked my father about his, my son will want to put pieces together, to find out what made me and, in turn, what shaped him.

My parents were temporary exiles from Ireland when I was born. After the successful run of Sharon’s Grave, Éamonn was offered the role of understudy to the male lead in the Royal Court production of J. M. Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World. They lived in a small flat in Camden Town from where my mother could visit the antenatal clinic at University College Hospital in St Pancras. In those days Ireland had no national health service and an attempt to introduce a mother and child welfare scheme had been defeated by the Catholic hierarchy. They considered it a first step on the road to communism.

In London my mother was given free orange juice and milk and tended to by a doctor from South Africa and nurses from the West Indies. Remembering this she told me: ‘It was the best care in the world. It was the kind of treatment only rich people could afford at home.’

On the day of my birth my father was out drinking and my mother went to hospital alone. It was early January and it had been snowing. A taxi driver saw her resting in the doorway of Marks & Spencer and offered her a free lift to the hospital. By now she would have known a few of the harsher truths about the disease of alcoholism. For one thing an alcoholic husband was not a man to depend on for a regular income or to be home at regular times. Éamonn appeared at the hospital later on and, as my mother remembers it, there were tears of happiness in his eyes when he lifted me from the cot and held me in his arms for the first time.

A week or so later I made my first appearance in a newspaper. It was a photograph of the newly born Patrick Fergal Keane taken as part of a publicity drive for a forthcoming film on the life of Christ. The actress Siobhan McKenna was playing the role of the Virgin Mary in the film and the producers decided that a picture of her with a babe in arms would touch the hearts of London audiences. McKenna was the foremost Irish actress of her generation and was also playing the female lead in The Playboy of the Western World. As a favour my parents had agreed to the photograph. In the picture I am held in the arms of McKenna who gazes at me with a required degree of theatrical adoration.

The declared reason for the embrace had nothing to do with film publicity. The actress had agreed to become my godmother. Strictly speaking this involved a lifelong commitment to ensuring my spiritual wellbeing. I was not to hear from Siobhan McKenna again. Holy Communion, confirmation and marriage passed by without a word.

Thirty years later I met her at a party held in Dublin to celebrate the work of the poet Patrick Kavanagh. My father had come with me. It was a glorious summer’s evening and Siobhan looked radiant and every inch the great lady of the stage. My father approached her and introduced me: “This is Fergal. Your godson.’

Siobhan smiled and threw her arms around me, and the entire gathering of poets and playwrights seemed to stop in their tracks as she declaimed: ‘Sure it was a poor godmother I was to you.’ She stroked my cheek and then stepped back, looking me up and down: ‘But you turned out a decent boy all the same.’

My father laughed. I laughed.

‘That’s actors for you,’ he said.

Éamonn and Maura both loved books. Our home in Dublin was full of them. I remember so vividly the musk of old pages pressed together, books with titles like Tristram Shandy, The Master and Margarita and 1000 Years of Irish Poetry. I have that last one still, rescued from the past. My father liked the rebel ballads:

Oh we’re off to Dublin in the Green in the Green .. ., Where the rifles crash and the bayonets flash To the echo of a Thompson gun.

My mother would sing ‘Down by the Sally Gardens’. Her voice trembled on the high notes.

Down by the Sally Gardens, My love and I did meet, She passed the Sally Gardens, With little snow-white feet. She bid me take love easy As the grass grows on the weir Ah but I was young and foolish And now am full of tears.

My parents were the first to foster in me the idea that I might someday be a writer. The first stories they read to me were Irish legends. As I got older they urged me to read more demanding works. I believe my first introduction to the literature of human rights came when my mother gave me a copy of George Orwell’s Animal Farm when I was around ten.

My father wrote plays and poems, but it was his gift for interpreting the writings of others which made him one of the most celebrated Irish actors of his generation. Sometimes when my father was lying in bed at night rehearsing his lines I would creep in beside him. After a while he would switch out the light and place the radio on the bed between us. We would listen to a late-night satirical programme called Get An Earful of This which had just started broadcasting on RTE. Get an earful of this, it’s a show you can’t miss. The show challenged the official truths of Ireland and poked fun at its political leaders. My father delighted in this subversion. In my mind’s eye I can still see him beside me laughing, his face half reflected by the light shining from the control dials of the radio, the red tip of his cigarette glowing in the dark and me falling asleep against his shoulder.

Nothing in either of my parents’ natures fitted the grey republic in which they grew up. Sometimes my father’s outspokenness could get him into serious trouble. Once he was hired to perform at the annual dinner of the Donegalmen’s Association in Dublin. The usual form was for the President of the Association to speak, followed by a well-known politician, and then for my father to recite poems and pieces of prose.

On this particular night the politician was a narrow-minded Republican, Neil Blaney, who in 1957 was Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, the department which controlled RTE, my father’s place of employment. At the time the government of Éamonn de Valera was making strenuous efforts to bring RTE into line after some unexpected outburst of independence on the part of programme-makers. My father later claimed that Blaney had denounced the drama department at RTE in the course of his speech to the Donegalmen. The historian Professor Dermot Keogh went to the trouble of researching the old files on the incident. He published the official memorandum a dry account of what was surely an incendiary occasion:

Before the dinner started Mr Keane left his own place at the table and sat immediately opposite where the Minister would be seated. When the Minister arrived, and grace had been said, Keane began to hurl offensive epithets across the table at the Minister and had to be removed forcibly from the Hall. Mr Keane was suspended from duty on 22nd November.

Quoting a civil service inter-departmental memorandum, Professor Keogh wrote:

Described as ‘a substantive Clerical Officer’ who had been ‘seconded to actor work as the result of a competition held in 1953’, Keane submitted ‘an abject apology in writing for his behaviour.’ He said he had been feeling unwell before the dinner and had strong drink forced on him to settle his nerves, with the result that he lost control of himself and did not realise what he had been saying.

The memorandum added tartly:

The action did not appear to Mr Blaney to be that of a man not knowing what he was doing. Mr Blaney said that Keane came very deliberately to the place where he knew the minister would be and that when Keane arrived in the hall he did not appear to have much, if any, drink taken.

Blaney was vindictive. My father lost his post as an actor and was sent to work as a clerical officer in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs. He didn’t last long and left to work as a freelance actor in Britain. Years later my father told me what he had said to Blaney. Drink was definitely involved but I think my father would have said what he had in any case. He told the minister that his only vision of culture was his ‘arse in a duckpond in County Donegal’. Keeping with the marshy metaphors he said that as a minister Blaney was as much use as ‘a lighthouse in the Bog of Allen’.

There was uproar. My father told me it was a price well worth paying. His verdict, nearly thirty years later, was: ‘That ignorant gobshite! What would he know about culture?’

Years later Blaney would achieve notoriety when he was sacked from the cabinet amid allegations that he had been involved in smuggling arms to nationalists in Northern Ireland.

My first memory of childhood is of clouds. They are big black clouds and they sit on the roofs of the houses in Finglas West. I see them because I have run out of the house. I cannot remember why. The garden gate is tied with string. I cannot go any further, so I stand with my face pressed against the bars and watch the clouds. The bars feel cold and I press my face even closer, loving that coldness. I keep watching the clouds, wondering if they will fall from the sky, what noise they will make when they hit the ground. But the clouds just sit there. Then I hear my name being called.