Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Burnt Toast»

Burnt Toast

Teri Hatcher

To Emerson, whose birth was the sole source of my personal evolution over the last seven years. Thank you for giving my life meaning. I will try not to eat as much burnt toast as my mom did—and maybe you won’t eat any ever.

And to my mother, for doing her best and for giving me material to write a book.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction Burnt Toast

Chickening Out

It’s Your Caviar, You Can Do What You Want with It

Place on Rack and Let Cool

Sour Grapes Can Make a Fine Wine

I’m Too Fried

Recipe for Disaster

It’s Pretty, Let’s Eat It

Once Burnt, Twice Shy

Dare to Compare Apples and Oranges

Will Work for Pie

Afterword: Happy Enchilada

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction Burnt Toast

Toast. Think about it for a moment. It probably has the simplest recipe in the world: one ingredient, one instruction. Still, you know when you’re trying to make it and you just can’t get it right? It’s too light or too soft, then…totally burnt. Charred in a matter of seconds – now it’s more like a brick than a piece of toast. So what do you do? Are you the kind of person who tries to scrape off the black? Or do you smother it with jam to hide the taste? Do you throw it away, or do you just eat it? If you shrug and eat the toast, is it because you’re willing to settle for less? Maybe you don’t want to be wasteful, but if you go ahead and eat that blackened square of bread, then what you’re really saying – to yourself and to the world – is that the piece of bread is worth more than your own satisfaction.

Up ’til now, I ate the burnt toast. I learned that from my mother – metaphorically if not literally. I can’t actually remember if she even likes toast or how she eats it. But what I know for sure is that although she was a loving and devoted wife and mother, she always took care of everyone and everything else before herself. This habitual self-sacrifice was well intended, but ultimately it’s a mixed message for a child. It taught me that in order for me to succeed, someone else had to suffer. I learned to accept whatever was in front of me without complaint because I didn’t think I deserved good things.

I can toast bread just fine. I don’t know about you, but my toaster only has one button. It’s a no-brainer. And still, I’ve been eating that metaphoric burnt toast all my life, and I think other people do too. Then I hit forty. Jules Renard said, “We don’t understand life any better at forty than at twenty, but we know it and admit it.” Admitting that there were things I still needed to figure out made me see this new decade as a chance to reconsider some of my behaviors. Did I really want to spend another ten years this way? The easy answer: no. The harder realization was that in order to change, I needed to stop eating the burnt toast. I had to be done anticipating failure. I had to be done feeling like I didn’t deserve good things, tasty things. And I was. I decided I was too old to continue this way. I didn’t want to do it anymore, and I don’t want other people to do it either. There is a way for us to value ourselves without taking away from anyone else. We should settle for nothing less than being good to ourselves and others. But it’s hard to break old habits. You can make a new piece of toast in a couple of minutes, but happiness takes work. That’s why I wrote this book. It’s my wacky, serious, skittish, heartfelt attempt to share my jagged route to happiness with other people like me.

Toast is small and simple, and maybe eating a lousy piece of it doesn’t seem like the worst thing in the world. Agreed. I can think of far worse things. But this isn’t a book about surviving worst-case scenarios. It’s about weathering the small challenges that we encounter every day. This scar that I have on my left shin might give you an idea of what I’m talking about. I got it when I was at the beach with my daughter, Emerson Rose. It was the first morning of our trip, and Emerson and I spent it playing in the sand and walking along the beach. In front of our hotel, about fifteen feet off the shore in a calm area of the ocean, there was a floating trampoline. Pretty cool, huh? I’d never seen that before. It looked like it was intended to be fun, but was it something I really wanted to do? Not so much. I didn’t want to be bouncing around in front of the whole beach in my less-than-supportive bikini. Nor did I want to plunge into the deep, dark ocean to swim out to the trampoline. Wading was just fine with me. Before I was a mother, I wouldn’t have gone near something like that. But I am a mother now, and I could see that Emerson was afraid, but curious. As a single mom I find myself in this situation a lot – there’s some adventure that doesn’t appeal to me, but there’s no one I can turn to and say, “Your turn, honey. Take Emerson out onto the trampoline.” Same thing when there’s a spider on the wall above the bed. That eight-legged intruder’s got to go, and it’s all me.

We swam out to the trampoline and bounced around for a while. Then Emerson wanted to jump off, but she was scared. I said, “Oh sure, let’s do it. It’ll be really fun. I’ll go first.” Now you and I both know that I did not want to jump off that trampoline. I was scared. But I don’t want to teach that to her. I don’t want to project my overblown imaginative worries onto her wide-eyed innocent hope. Now the thing about this floating trampoline is that it wasn’t very bouncy, and what little bounce it had was weird and off-kilter, so you couldn’t really plan your trajectory. But my daughter was waiting and watching, so what could I do? I flew off the trampoline into – a huge belly flop. A belly flop looks funny. It even sounds funny. But I’m here to say: It’s. Not. Funny. My stomach, my arms, my legs – all my skin burned. I was instantly red and tender all over, but I didn’t want Emerson to see that I was in serious pain. That wasn’t the lesson I wanted to teach. I knew she could do it and I knew that she, unlike her aging mom, would be fine. So I popped my head out of the water and said, “That was so fun! Give it a try.” She jumped straight off, loved it, of course, and did it again and again. When we got back to the beach, I saw that I had a long cut on my leg from the water (who knew that could happen?). Emerson noticed the blood, and I shrugged it off with some stupid excuse. I was in agony, but I didn’t want to cry in front of Emerson. Instead, I got a rum-infused coconut beverage from the guy walking down the beach and subtly iced my wound.

Now I look at the scar on my leg and wonder if I did the right thing. Should I have let Emerson know that I was hurt? Should I have called over a (preferably cute) lifeguard for some first aid? Why didn’t I do that? Why did I hide the truth about what was going on with me? Did I do it for her or for me? Was I trying to be cool or tough? There’s an emotional experience embedded in that scar. There’s a lesson locked in it. I’m done making silent self-sacrifices. I’m done hiding the truth. Here it is. Have at it.

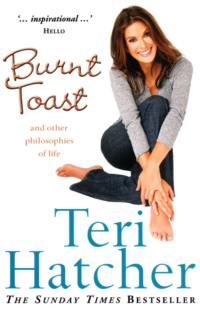

I hope you’ll discover as you read this book that vulnerability plays a key role in my life. It’s hard for me – I have trouble admitting that I need other people. I’ve always tried to be honest about my fears and insecurities and self-doubt. When I was doing the photo shoot for the cover of this book, I spent the first hour thinking, This is ridiculous. I haven’t even written the book yet. (I guess this is how they do things in the world of publishing – they need the jacket before the book’s done.) So I was up there posing and thinking, Maybe there is no book. Maybe I have nothing to say. Maybe I’m just an idiot. Who do I think I am? Then I started talking to the photographer and the makeup guy and the wardrobe guy and the photo assistants. We were laughing and feeling good, and suddenly someone revealed that, like me, he’d had no sex on his honeymoon. We both had felt embarrassed and inadequate, like we were the only people in the history of time who couldn’t get it together to have sex on a honeymoon. And I said, “See, we really are all the same!” Maybe this is too much information for an introduction – I’m already telling you about my sex life (or sad lack thereof) and I’m only on page 4. (It was the publisher’s mandate – write whatever you want so long as you mention sex before Chapter 2.) But that’s what this book is about – how when we feel fragile and vulnerable and hopeful and human, we’re not alone. And if I can have these feelings and work through them then you can too. My hope for this book is that you’ll read it in the bathtub. Maybe with a glass of wine. And that you’ll laugh a little and feel a little inspired.

Just because I’m up front about this stuff doesn’t mean I’ve figured it all out. Not even close. Even if I do have some good ideas about how to help you live a happier life, I’m not sure I always practice them, and I certainly don’t practice them every day. It’s too hard. Some days I’m like Alice, trapped deep down in that rabbit hole. And instead of trying to find my way out, I just hide away, watch B movies until I can’t keep my eyes open, and then sleep for a really long time. But I rarely have time for that self-indulgence, so I put on my mom clothes or my “Teri Hatcher” costume, as I like to call it, and pretend everything’s fine.

In my scrapbook from 1999 there’s a fortune-cookie fortune that says, “Your luck has been completely changed today.” But you don’t change in a day. Just because you’re getting older or more successful doesn’t mean you automatically grow as a human being. You learn things when life presents you with an opportunity and you’re ready to receive it. When Desperate Housewives came along, I was, like many an aging female actress in Hollywood, a big has-been. I’ve made no secret of that. I never expected to get a second chance, though I must have saved that fortune in hope that everything actually could change overnight. When it did, when Desperate Housewives became a hit, I suddenly had the job and security and affirmation that I’d given up on long before.

Over time, when they don’t come true, you lose sight of your dreams. Years go by and you look back and wonder how you got so far without starting a band, making a sculpture, doing the things that you wanted to do but couldn’t because now you have a family or kids or a mortgage. For whatever reason, it didn’t ever happen. So when my dream actually became reality, my response wasn’t “better late than never.” I’d just turned forty, was a divorced mom of a young daughter, and I didn’t want to simply ride my wave of success. I wanted to live it – not as the twenty-year-old who desired it, but as the forty-year-old who worked hard for it but thought her opportunity had passed. It woke me up to the realization that though life is unpredictable, things can change for the better, dreams we thought were long past can still come true, and that we increase our chances of that happening by believing that we are deserving – of golden-brown buttered toast, and success and happiness. Mmm. I’m getting hungry.

I wrote most of this book sitting on the floor in my living room. I like the floor. There’s no place to fall. The first time I sat down with a little blank book, a pen, and the mandate from my editor to start writing down my thoughts and feelings, I stared at the page. Before I could hook any of the ideas that worm their way in and out of my tired brain, I just sat there in awe. Wow. I have an editor. I wrote that down. And crappy penmanship. I wrote that down too. Yeah, I’m finally old enough, used enough, hailed enough to put some of it on paper. That got me started. I kept going until the first page was almost full and I was on to the next, but my hand was starting to hurt. I’d finally seen, touched, and tasted enough; I’d loved, struggled, and learned enough to have a tale to tell, and my hand was having an arthritic attack. Leave it to me to figure out how to stand in my own way. Time after time as I shuffled through scrawled notes and fragmented thoughts, I was paralyzed by my lack of confidence. This wasn’t an unfamiliar state of affairs. No matter what the challenge before me – an audition, a photo shoot, writing a book, or a relationship – for all my past accomplishments, I torture myself on the way, always wondering, Why would they pick me? Why am I good enough to do this? He’ll never like me as much as I like him. Who the hell do I think I am – I’m not that special. This book itself was a journey for me. Writing it forced me to face my self-doubt and fears – the same kind of struggles that this book contemplates. I kept thinking, I need to read this book. In fact, I’ll probably be the first one to buy a copy because then a) I’ll know that at least one copy sold and b) I really will be able to remind myself of the lessons I’ve learned every once in a while.

The lessons here are about how to forgive, love, enjoy, and explore yourself as a woman. I’ve finally gotten to a place where I’m easier on myself. I’m comfortable and happy being a mother. Being in my body. Feeling sensual as a forty-year-old woman. Most of the time. I sure hope you’re one of the people who managed to have sex at some point during your honeymoon. Good for you! But if you’ve ever felt like a spicy gumbo of fear and confidence, despair and hope, desire and satisfaction, mother and child, pretty and ugly, strong and weak, then read on. The journey’s a whole lot easier if we take it together.

Chickening Out

Imagine this. It’s a sunny Sunday and you’re meeting some friends for a picnic at a lovely spot that’s mere minutes from your home. (Hey, it’s a fantasy – we might as well make it convenient.) You’re in a great mood, and you even brought a yummy gourmet lunch that someone else prepared. (Again: fantasy.) When you arrive at your idyllic, balmy destination, it turns out there’s a lake, with an outcropping of rock jutting out over it to form a natural high-dive. It’s high enough to be scary, but low enough to be safe. There are screams of joy as an endless line of people jump off. Okay, now here’s where I want you to drop the fantasy and consider the situation as if it were real. The question is: Are you the kind of person who climbs right up, takes in the view for a fraction of a second, then plunges off the edge without a second thought? Or do you stand there, trying to get your guts up to jump, and after a few minutes decide it’s too scary and climb back down, admitting defeat? Are you the daredevil, or the wimp? The good news (I hope) is that I’m not here to talk about how brave the first person is, and how the second person is a pluckless chicken who should learn to face the world with guts and determination. No, the way I see it is – if you’re either of these people, you’re lucky. You know what makes you happy, you know your limits, and that’s that. But some of us are stuck in the middle, making life a whole lot more complicated than that. I’m the one who found myself standing frozen at the top of a twenty-five-foot-high rock platform looking down at a placid Sedona lake. I’m the one who stood there, not for ten minutes. Not for half an hour. I stood there for over an hour trying to convince myself to jump. Torturing myself over this pointless, supposedly fun activity. Half terrified. Half hating my own terror. Half wanting to be the kind of person who jumped. Half wanting to climb down and eat some potato salad. That’s right. Four halves. That’s what I’m talking about: a schizophrenic war with myself.

After a good hour and fifteen minutes, I finally jumped off that stupid rock. By then I was so tired of arguing with myself that I was ready to kill myself anyway, so what harm could it possibly do? I did it. I jumped. When I surfaced, there was some biker guy by the edge of the lake clapping for me. He said, “That’s the longest I’ve seen anyone stand up there looking and still jump.” That’s me. I may be scared and conflicted about something, but I go through with it. And for what? Was it fun? Are you kidding me? It was completely anticlimactic. It’s just like sex – too much deliberation kills the mood. It wasn’t even close to fun. All I gained from my jump was the right to tell myself that I hadn’t given up. I’d passed another self-imposed test. Yay me.

You know what they say – you can tell a lot about a person by how they jump off a cliff. Okay, maybe they don’t say that. But it’s not just an isolated afraid-of-heights type of thing. Not for me, anyway. It’s part of my everyday life – that top-of-a-cliff fear, hyper-analysis, internal conflict. That circular contemplation of how I feel, who I am, and who I want to be that keeps me paralyzed on cliff tops for ridiculously long periods of time. I’ve always doubted my abilities and had trouble acknowledging my own success. Take a bet I once made regarding a limousine. If you think I stood on that cliff for a long time…let me tell you, the limo thing went on for years.

It started when I first moved to Los Angeles. I was living in North Hollywood. My next-door neighbor, I’ll call him Ned*, didn’t have a refrigerator and one day he asked to borrow ice and we became friends. (What kind of girl actually believes a guy who knocks on her door to borrow ice? Me, that’s who. Nineteen years old, fresh off the Silicon Valley chipwagon, and plopped into a city where the women were faster than the cars.) Anyway, along the way Ned and I made a deal. It was after I got my first part, playing a dancing, singing, lounge act mermaid on The Love Boat, and the agreement was that whoever of us became a star first had to rent a limousine. Then we’d spend a whole day driving around in our glamorous stretch limo. Doing what? Doing regular errands: going to McDonald’s, picking up the dry cleaning, buying ice (Ned only – he had to keep up the charade). We’d just cruise around doing nothing out of the ordinary, as if renting a limo were just another ho-hum part of our lives. Nothing was further from the truth. I could barely afford the dry cleaning that we would theoretically go to pick up. Growing up, our family car was an orange Chevy Vega with a black stripe down the middle and Neil Sedaka permanently stuck in the eight track. The only limo I’d ever been in was the one my date and his friends rented for my senior prom, and it was white, which (I now know) is absolutely unacceptable in Hollywood. To me, limo equaled private jet equaled swimming pool filled with Dom Perignon – none of which I’d ever seen, ridden in, or dove into. Extravagant beyond what I ever imagined I could experience.

When push came to shove, I wasn’t good for the limo bet. When I had my TV Guide debut for a short stint on a soap opera, Capitol, Ned said, “You made it! You’re in TV Guide. Looks like you owe me a limo ride.” But I shook my head. No way could I accept that I’d been successful at anything. “Not yet. I haven’t made it yet.” In fact, I kept my waitress job at an Italian joint in the Valley and worked there after filming the soap opera all day. Time passed, and eventually I got my first part in a feature movie, The Big Picture. Well, when Ned heard the news, he said, “Okay. This is the big time. You’re in a movie, and it even has the word ‘big’ in the title. Now where’s our limo?” But still I resisted. It became an ongoing joke between us – when I got my second and third movies, when I got cast in Lois & Clark, I always argued, “I’m a small fish in a big movie!” or found some other reason that it didn’t count – why I still hadn’t “made it.” It may sound like I was an ambitious go-getter, never satisfied, always needing to climb to the next rung. But I was actually just full of doubt. I was too worried that it would all disappear overnight, that the acting police would come pounding on my door at 3 A.M. with documents revealing that my only acting education was a six-week summer program at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, demanding my Screen Actors Guild card back and accusing me of fraudulent claims of talent and attempted mugging (the face kind, not the purse-snatching kind). I couldn’t revel in my success – even when it came. Sort of like finally jumping off the cliff into that lake in Sedona. By the time I managed to get there, I was long past enjoying it.

Self-doubt runs deep. I’ve been this way my whole life. It’s hard to pinpoint why. It’s not like your parents sit down and figure out the best way to screw you up and then embark on an organized execution of the plan. Sometimes I wish that life could be more like golf. I know, I know, if there are two things the world doesn’t need any more of it’s types of wine openers and analogies about golf, but bear with me. Unless you take the game super-seriously (you know, the type who throws his club at the duck that quacked during his tee shot), which I don’t, each shot is a brand-new opportunity, totally disconnected from the shot before and the shot after. Each hole is a new chance to perform and succeed and be a great golfer. Golf is zen like that. But that’s not how life works. Small decisions, occasional traumas, incidental inconsistencies – everything adds up in odd, unpredictable, conflicted ways. Each moment is weighed down by its own set of baggage from the past, and we’re messy bundles of self-protection and reaction to our uneven, un-choreographed experiences.

In early high school, when I was taking geometry, I remember showing my math-genius dad a problem I’d solved correctly. I probably hoped he’d be proud that I was learning a little bit of his field. He looked at the paper and said, “You know, there are three other ways to solve that problem.” I said, “I got it right, didn’t I?” I wasn’t really interested in alternate solutions. I’d managed to do it the way the teacher had taught us and that was enough. He handed the paper back to me and said, “You’re a brick.” He didn’t mean it in the jolly old English use of “brick,” as a dependable chap. Nor was he referring to my abs. He went on, “You should be a sponge, but you’re a brick.” He meant that I wasn’t as open-minded or curious as he wanted me to be. I had shown my dad my correctly done math homework, and he in turn found something wrong with me. Getting the right answer wasn’t enough.

He was also the kind of dad who always beat me at chess and ping-pong. I think he just never found the balance of trying to teach me to be good at something, and realizing that since I was a child it was highly unlikely that I’d ever beat him at anything (he’s changed as a grandfather). I wonder if he thought he was building my character by continually reminding me that I wasn’t good enough to win, or if he thought losing shouldn’t matter to me. But it did. As a kid, if you lose enough times you quit trying. You have to be taught the balance between the effort it takes to improve and a realistic view of your capabilities.

My mother, on the other hand, thought everything I did was perfect. She thought constant praise was the way to show love and build selfesteem. But if you’re perfect in your mother’s eyes, imagine how far you fall when you find out you aren’t perfect in the eyes of the world. And no kid is, not even me, though if you look up “goody-goody” in the dictionary, you’ll find my name. So I had one parent teaching me to lose and the other teaching false confidence. Parents can fall into traps like this. If yours were anything like mine, they didn’t mean to be harmful. I learned to be a loser, to manage failure, to expect that even my best efforts wouldn’t fulfill expectations, and that I would never be good enough at anything. Ironically, I became great at having that attitude.

When I was fourteen or fifteen, I auditioned for the San Francisco Ballet. I went with some of the other girls in my dance class. I knew they were all better than I was, and, not surprisingly, I didn’t get in. I still have the rejection letter. Why save it, you might wonder. Was it that important to me? Was I that heartbroken? Not exactly. But the scrapbook I made while in high school had a section titled “Failures,” and that’s where I kept the letter of rejection, along with a few photos of ex-boyfriends. How’s that for being a good loser? I kept a record of my losses the way others might carefully preserve their ribbons and medals. Like I wanted to have a physical place to affirm the notion that I was not good. (Can you say therapy? Don’t worry, I got there eventually.)

I may have been a brick instead of a sponge, but I still ended up a maths major in college. (Well, junior college. I’d been planning to transfer to Cal Poly, but I never made it. Who wouldn’t sideline calculus for a chance to work for Captain Stubing on Love Boat?) Maybe that’s why I tend to look at my life as if it’s a problem to be solved. I calculate all the possible scenarios – or at least all the bad ones – analyzing, judging, protecting, defending. Like there must be a right answer if only I could find it. But there isn’t and I can’t. Life isn’t two plus two equals four. I wish it were that simple and clear cut.

You only get one life, and it’s supposed to be fun, isn’t it? Of course we all have to work, but isn’t the point of working hard to succeed and to use that success to secure yourself a well-earned, hearty chunk of fun? Having fun is letting go. Letting go of all that analyzing and planning and second-guessing yourself. But it can be really hard to do. In small doses, cautious doubt is healthy – you keep things in perspective and don’t set yourself up for disappointment. But I let it get out of control. And sometimes that doubt creeps into other parts of my life – from my friendships to my social life to exercise to work.

It’s really easy for me to foresee my own failure. If I’m trying out for a part I tell myself, They’ll want someone younger. Or blonde. Or left-handed. Basically, they won’t want me. But I still try as hard as I can. It’s all a silent, internal battle that I try not to let have a visible effect unless, or until, something brings it to the surface. Around the same time I was up for a part in Desperate Housewives, I was also up for a part in another ABC show – a sitcom. A sitcom can be an easier gig than an hour-long show, at least in terms of the work schedule and hours. So I figured that even though I loved the Desperate Housewives script, the sitcom was my top choice since it jibed better with my priorities as a single mom.

I went in to test for the sitcom first, doing a scene in front of some network executives from ABC. I felt comfortable; people laughed; I thought I did great. That night, I waited for the phone to ring and…nothing. Nothing that night. Nothing the next day. I was having a nervous breakdown. When I finally heard back, I hadn’t gotten the part. Okay, that’s happened before – just another memento for the failures page. But what killed me was that word came back that somebody in the room thought I had an attitude. Like I had a chip on my shoulder or thought I was too fancy to audition. Well, that sent me reeling. I couldn’t believe it. It was so untrue. It’s even hard to share this story with you because I worry some of you will believe I did have an attitude – you remember that feeling you had when you were a kid and your parents thought you were lying about something and you weren’t, but there was no way you were going to change their minds?

When I was fifteen I was at my boyfriend’s house. My mom came to pick me up in our Chevy Vega, and before we drove a block, she pulled over and insisted that I’d been smoking pot. Well, I hadn’t and I told her so. Hell, I didn’t even know what pot was. (I wasn’t kidding about that goody-goody thing.) But she kept insisting she could smell it on my breath. What happened to being innocent until proven guilty? I guess that constitutional right went out the Vega window and was replaced with her lack of confidence that I was an honest person whom she could trust to just answer a question directly. No, somehow I’d become a plotting, manipulative bad seed and it was my mother’s obligation to shuck me out. Well, I did prove my innocence by producing a tube of lip gloss. Yes, it turned out to be the dreaded grape-flavored Bonne Bell Lip Smacker. That sweet smell she was associating with pot was just lip balm. Then again, I was guilty of too much kissing.

Not being believed is a real emotional trigger for me. I was more upset about that than about not getting the sitcom job. I really wanted that job, and I’d been excited to audition for it. How had I given off an arrogant vibe? How could I be so disconnected from the people around me? Those questions spiraled into worse thoughts. It was horrifying to be perceived as arrogant or presumptuous. Ugh. I must be an awful person to create that impression and to be so oblivious to it. The thoughts went on and on like that. Blaming myself and only myself. The upshot is that I cried for 18 hours straight. That’s right – it’s not a typo. (Unless it says 180, in which case it is a typo – it should read 18.) Again, I wasn’t crying about not getting the part, but about a lifetime of feeling misunderstood.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.