Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Billy Connolly»

Billy

PAMELA STEPHENSON

To the Connolly and McLean families, in the spirit of healing through understanding; and to all families who are divided by religious differences, or who struggle with poverty, abuse or addiction.

‘He must have chaos within him,

who would give birth to a dancing star’

Nietzsche

Contents

Introduction

1 ‘Jesus is dead, and it’s your fault!’

2 ‘He’s got candles in his loaf!’

3 In Search of a Duck’s Arse

4 Oxyacetylene Antics

5 Shaving Round the Acne

6 Windswept and Interesting

7 ‘I want to be a beatnik’

8 ‘See you, Judas, you’re getting on my tits!’

9 Big Banana Feet

10 Stairway to Hell

11 Captain Demento and the Barracuda

12 ‘That Nikon’s going up your arse!’

13 Legless in Manhattan

14 There’s Holes in Your Willie

15 Pale Blue Scottish Person

16 Nipple Rings and Fart Machines

EPILOGUE: Life, Death and the Teacup Theory

Plate Section

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Much has been written already about the chimerical joker known to the world as ‘Billy Connolly’. That creature, however, is a fictional one, a Bill-o’-the-wisp that dances from tabloid to tome with relentless inaccuracy. Nothing unusual about that: everyone who comes to public attention is reflected in fragments, half-truths and downright lies since every observer projects his own fantasy upon the famous person in an illusory folie à deux. In any case, when it comes to chronicling a person’s life there is no such thing as absolute reality, even if the writer happens to be his wife and a ‘shrink’ to boot. I, for one, subscribe to the notion implied by the Heisenberg Principle, that nothing in the universe can ever be accurately observed because the act of observation always changes it. For every one life, there are a million observed realities, including several of the subject’s. ‘A stranger caught in a portrait of myself,’ as Nabokov described the phenomenon, is commonly reflected back to a bemused interviewee.

‘Who HE?’ Billy will shout, slapping down the latest visual or written appraisal he considers is a dark imitation of his former self. In my paradigm, every person holds the reality of his own experience either in his mind’s eye or just below the surface of consciousness, or even deeper in the unconscious mind; but in the latter level we are all strangers, even to ourselves, and the mysterious workings of our unfathomed parts are revealed only in our dreams. Even within families, shared times are experienced differently, coloured by the age, family role or state of mind of each member. Small wonder, then, that some of Billy’s relatives and friends have disparate impressions of the following events. For Billy, reading each chapter after completion has elicited the shock of self-confrontation, accompanied by frequent laughter, occasional fury and a few precious tears as he painfully re-experienced many traumatic events. Most rewardingly for the author, the process of drawing together the following occurrences and providing insights might well have been a catalyst for his further healing, although Billy will have none of that: ‘Pish!’ he cries. ‘As my old granny Flora used to say, “The more you know, the less the better.”’ Another gem of Flora’s was: ‘Never clothe your language in ragged attire.’ Billy obviously missed the word ‘never’ because, purely in an attempt to please his dear old gran, he continues to say the ‘f ’ word in every single sentence and double on Sundays. I actually wondered about Tourette’s syndrome when I first met him. People try to stop Billy’s profanity, but that only encourages him. I myself have found great utility in those special collars for large pet dogs, with the remote control device that administers savage electric shocks to the neck of any beast that gets too close to the mark. Undetectable beneath his polka-dot shirt collar, it came in very handy recently when Billy gave a graduation address at our children’s school. You know where this is leading … try to guess the number of ‘f ’ words in this book before you read it. Be creative: it’s just like guessing the number of marbles in a jar so run a sweep, raise money for charity or decide who buys the next round. The answer can be found later.

I’m just playing with you. When this book was first published, people were frantically turning pages to satisfy their mathematical sensibilities. This was a trap. If observed, one risked being accused of committing the appalling readers’ crime of turning to the last page for an unearned glimpse of the ending. But by now, almost everyone who picks up this book knows how Billy’s childhood story ends – with the triumph of a successful life as a beloved comedian. However, the paragraphs above were written ten years ago, when HarperCollins was just about to publish Billy for the first time. It was a nerve-wracking time. In the run-up to publication, both author and subject were mightily scared because this book is not what people might have been expecting – a frothy romp through the life and times of Billy Connolly, funny man and hilarious raconteur. Oh, one could write a facile account of him (the time that silly big man ran naked round Piccadilly Circus, got drunk with Elton, and danced with Parky) but, in my opinion, that would be dishonest. No, there’s much, much more to his story and, both as a psychologist and as Billy’s wife, I believed the truth was begging to be told.

Billy’s real story is a dark and painful tale of a boy who was deprived of a sense of safety in the world. This early trauma had a massive influence on the man he became – a survivor of abuse whose psyche still bears the scars, and whose resultant, deep self-loathing prompted self-destructive tendencies. My many years working as a psychotherapist have taught me that it is usually healing to bring one’s dark secrets into the light and find that one is still accepted and loved. And ever since I caught my husband crying by the TV when psychologist John Bradshaw was helping a man come to terms with his childhood abuse, I wanted that for Billy.

But he was afraid that, when readers discovered his ‘shameful’ secrets, they would turn their backs on him out of scorn, pity, or embarrassment. And I was concerned that, having convinced him to tell the world his extraordinary story – and being the architect of that decision – I bore considerable responsibility for the outcome. What if it went wrong? What if I had misjudged how people would react? What if Billy became retraumatized by it all? Public revelations cannot be retracted. And revisiting terrible events under the wrong circumstances can cause further harm.

Fortunately, many of the millions of people who read Billy reached out to my husband in wonderfully positive ways. We were both unprepared – not only for the unprecedented success of the book, but for the massive and widespread outpouring of support and acceptance. Readers let Billy know how much they empathized with him, adored him and, in many cases, shared similar stories of violation, torture and humiliation. Far from being rejected, Billy became a poster child for those who seek to overcome the challenging legacy of a painful childhood, who hope eventually to find that the revenge of survival and future happiness – let alone success – is sweet.

Billy and I received hundreds of letters from people who poured out their own, touching stories of childhood torment. Some even said this was the first time they had dared tell their own story, and that it was Billy who had finally given them the courage. It made Billy very happy to learn that others gleaned hope and healing from his story. And for me, it was particularly gratifying to learn that the book seemed to help depressed, abused, or hopeless people.

There’s nothing like facing the demons from one’s past – wrenching them from the realm of the unconscious and talking about them with an empathic person – to lead one to a sense of peace and a healthy perspective. Nowadays, Billy speaks compassionately about his father, and says he has forgiven him. But that’s no easy task for any survivor of abuse; psychologists know that forgiveness and healing do not necessarily go hand in hand, and I am well aware Billy still harbours reserves of fury that may never, ever be assuaged. He continues to be a somewhat tortured soul, occasionally as insecure and frightened as he was as an abandoned four-year-old. And he still struggles with his attention disorder (which is only a problem offstage, since losing his way while telling a story has become an aspect of his stand-up concerts that audiences thoroughly enjoy). He also struggles with short-term memory, organization, gaining a gestalt perspective on anything, and anxiety; pitching himself on stage has not become any easier than it was when he first started.

But no one calls Billy ‘stupid’ like they did when he was a schoolboy – least of all me. Billy is one of the brightest and best-read people I’ve ever met. However, like many others of his generation, he is challenged by the cyber world. He still thinks of the Internet as ‘The Great Anorak in the Sky’. ‘It’s getting worse and worse,’ he complains. ‘It’s made people fucking boring. It’s separating them. Now they’re all sitting in rooms typing to people they don’t know.’ In fact, Billy’s current enemies are inhuman ones: Internet access, passwords (the remembering of them), and ‘How do I get the Celtic scores on this raspberry … blueberry … or whatever the fuck it’s called?’

Yes, Billy is still an expert in the fine art of swearing. He is also the proud owner of a Glaswegian accent, which has mellowed only slightly over the years. In fact, when I first met the man I could barely understand a word he said, and sometimes I think that was a blessing. Now, I love the Scottish accent, but at home it can lead to the ‘Chinese Whispers’ kind of misunderstanding. Once, when Billy and I were watching the TV news with our adult children and some extended family, I commented that I adored the CNN reporter Anderson Cooper. ‘Grey-haired cunt!’ retorted my husband, in what seemed like jealous pique. Everybody looked at him in alarm. ‘Billy!’ I cried. ‘What’s that poor man ever done to you?’ Billy stared at me, mystified. It turned out he’d actually said ‘Great hair-cut!’

Over the years, Billy has gradually suffered a little hearing loss, which means he is even more likely to talk about someone in loud, disparaging terms, imagining they can’t hear. A few Christmases ago he fell asleep in the middle of a family outing to the seasonal Rockettes show at Radio City Music Hall in New York – high-kicking glamour girls in furry bikinis, a ridiculously jovial Santa, and way too much fake snow. The kids and I took it in turns to try to keep him awake, or at least minimize his thunderous snoring, until we realized that this was a lost cause. Halfway through the show he suddenly woke up and, to our deep embarrassment, shouted above the orchestra: ‘For fuck’s sake, Pamela, how much more of this shite is left?’

After Billy I wrote a follow-up book about him – an account of his sixtieth year – called Bravemouth. Once that had been published I decided it would be remarkably unhealthy – not to mention annoying – to write a single word about him, ever again. Frankly, I was exhausted from focusing so unswervingly on my husband; that was well above the call of duty for any wife. ‘I’m sick of you,’ I announced at last. ‘In future, write your own stuff!’ I went on to have adventures in the South Seas and Indonesia, and also scribbled away on the subjects of psychology and sex. It was such a relief.

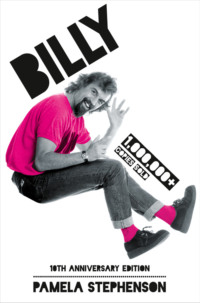

But who exactly is our protagonist nowadays? Well, he’s much the same. We now live in New York, where Billy can be spotted tramping the downtown alleys in search of an elusive banjo music shop, a cigar den, or a purveyor of outrageous socks. His sock choices have changed a little over the years; he has gravitated from the luminous to the gaudy stripe. Now he prefers a horizontal red, turquoise, orange, brown, and white repeating stripe to those he was wearing on the original Billy cover: luminous pink, with pictures of Elvis on the ankle. ‘I still love those,’ says Billy, ‘but I find them awful hard to find.’

Billy claims to be part of an unofficial ‘inner circle’ of people who wear wild socks. ‘We like each other,’ he says. ‘We always give each other a nod in the cigar shop.’ Billy says he’s never met a cigar smoker or a fl y-fisher that he didn’t like. He seeks to land ‘a wee troutie’ in every brook he can find, from Canada to New Zealand, while New York cigar dens have replaced Glaswegian pubs as the haunts where Billy can enjoy largely male company. ‘My New York pals,’ he says, ‘are a great cross-section: Wall Street guys, New York cops, and Arthur who makes art from bashed-up cans that have been run over by cars.’ Nevertheless, Billy keeps close contact with his Glasgow chums. He frequently returns to his home town – where he was recently honoured by being presented with the Freedom of the City of Glasgow. ‘It’s fucking great,’ said Billy. ‘According to old by-laws I can now graze my cows on Glasgow Green, fish in the Clyde, and be present at all court hearings! And if they send me to jail I get my own cell; no bugger’s going to interfere with my jacksie.’

Billy definitely does not restrict his friends to other living national treasures, although he is beloved by many of that ilk. ‘He is inspirational and I absolutely adore him,’ said Dame Judi Dench. ‘One-off, unique, irreplaceable,’ echoed Sir Michael Parkinson. ‘The most frankly beautiful Scottish person with a shite beard I ever met,’ said Sir Bob Geldof. Billy is considered a ‘comedian’s comedian’, and he’s extraordinarily generous in his appreciation of others in his field. ‘He’s my inspiration,’ said Eddie Izzard. ‘He was doing alternative comedy fifteen years before anybody else.’ ‘He is the funniest man in the world,’ said Robbie Coltrane. But it was Billy’s close pal Robin Williams who summed it all up when he said: ‘I don’t have a clue who Billy is.’

Age has not slowed Billy down, and I suppose it’s remarkable that he continues to have a flourishing career, both in movies, television, and in his live performances. The run-up months to London’s Olympics alone have seen him undertake a major, sold-out UK tour of forty-two dates. And Billy still seems to hop from one movie to another. One of the highlights of his movie career in recent times was Quartet with Maggie Smith, Michael Gambon, Pauline Collins, and Tom Courtney, about four ageing opera singers who live together in a residential home. It was directed by his pal Dustin Hoffman, who once described Billy as ‘a big fart that carries no offensive odour’.

A fantastically entertaining TV series about Billy’s trike ride from Chicago to Los Angeles, along the USA’s famous Route Sixty-Six, was broadcast on ITV in 2011 – although Billy was lucky to finish it. The day he neared Flagstaff, Arizona, I was doing something that hardly befits a psychologist – having my photograph taken for a newspaper. ‘What’s your husband up to?’ asked the photographer. ‘Oh, he’s riding his trike along Route Sixty-Six for a TV show,’ I replied. ‘Really?’ said the man. ‘I’m a Harley biker myself.’ ‘Oh, thank heavens I’ve persuaded him away from those things,’ I said. ‘Trikes seem to be a lot more stable.’ The photographer’s next words were portentous. ‘Not necessarily,’ he said. ‘They can tip if you turn them in too small an arc …’ I sighed and made a mental note to address that the next time I saw my husband. It could not have been more than five minutes later that Billy’s manager Steve called. ‘Billy didn’t want to worry you,’ he started. ‘He’s OK, but he came off his trike.’

I felt the sensations of shock flood into my body. ‘What happened?’ I asked Billy, when I finally managed to speak to him. ‘Oh, I tried to copy a manoeuvre of the camera van (which has four-wheel drive). See, Route Sixty-Six is shaped like a snake, and running through the snake is the interstate highway, so there’s a series of dead ends that means you often have to go back. Anyway, we came to a dead end where they’d bulldozed the dirt onto a hillock. The van managed to drive on top of this mound and turn round, but when I tried it I was going too fast and my trike fell on top of me.’ ‘What injuries do you have?’ I asked. ‘Och, I just broke a rib and skinned my knee cap very badly. It’s a very pretty shade of purpley red. My finger is all swollen and I had to get my wedding ring off. But I’m in very little pain. They had to hold me down – I didn’t think I was hurt so I wanted to get up.’ Before long, Billy was in a helicopter on his way to Flagstaff Hospital. A medic was kneeling by his stretcher. ‘What kind of pain are you in?’ he asked. ‘I’m OK,’ replied Billy. ‘If ten’s the worst pain you’ve ever felt, where are you now?’ asked the medic. ‘About one and a half,’ replied Billy, nonchalantly. ‘Are you sure?’ asked the medic, incredulously. ‘You’ve just broken a rib!’ But Billy stuck to his story. ‘Look, you can tell me,’ the medic said insistently, waving a morphine drip. ‘I’ve got the whole candy store here …’

But Billy eschewed the pharmaceuticals and entertained the medical flight team instead. It could have been a lot worse. By the time I spoke to him in Flagstaff he’d been X-rayed, stitched up, and released. His cheery voice and attitude betrayed his idiosyncratic and macabre view of the world, as well as his attention to curious detail. ‘The emergency doctors had to cut off my nice leather jacket,’ he said, ‘but they’d done that to bikers so many times before, they knew exactly how to cut the seams so it could be sewn back together again!’ Hardly what I wanted to hear. And hardly reassurance that he had learned any kind of lesson from his accident. ‘Billy, you seem to care more about your leathers than your own skin,’ I said. ‘From now on, do you think you could manage to stay off any kind of road vehicle that lacks a roof?’ ‘Pish bah pooh,’ was his predictable response.

As you’ll discover in Chapter Two, Billy has been a risktaker from early childhood, and I’ve often wondered how he managed to make it to his teens. I now understand that his apparently reckless early stunts were instigated as much by despair as by dare-devilry (depressed, abused, misunderstood children often engage in activities that psychologists recognize as signs of passive suicidality). Hopefully, this most recent mishap may have curtailed Billy’s vroom-vroom craziness to some extent. Trying to be the voice of reason is exhausting for me, and anyway, he is understandably unwilling to accept warnings from a woman who delights in facing storms on the high seas, travelling in hostile environments, and scuba diving among sharks of every variety.

As I write this, Billy is preparing to leave for New Zealand to start work on the latest Peter Jackson blockbuster movie, The Hobbit, in which he will play the King of the Dwarves. Aghhh! It’s so trying for me that he should have such a part. Not because he’ll be away from our New York home for three months – no, we’re used to long separations. It’s trying because Billy regards the legitimate use of the word ‘dwarves’ as a triumph over my long-standing protestations that it’s ‘not politically correct’. In my presence, he loves to tell a tale about a little person – whom he calls a ‘dwarf ’, just to see me squirm. The following is the tale, with ‘little person’ substituted for ‘dwarf ’:

Apparently, a pal of Billy’s sister Florence was on a Glasgow bus when a woman who happened to be a little person got on. A schoolgirl stood up to offer her a seat, but the woman declined. ‘You’re just giving me your seat because I’m a little person,’ she said. ‘I can stand perfectly well.’ A bit later, another woman, who was about to get off, waved the little person towards her seat. Another sour ‘I don’t want it’ was the response, which geared the giver onto her high horse. ‘I’m not offering you this seat because you’re a little person,’ she shouted. ‘I’m offering it because you’re a woman. And by the way, I think you were very unfair to that young schoolgirl, who was just trying to be nice!’ At this point in the story, Billy always starts to giggle in anticipation of the punch line. ‘And what’s more,’ continued the woman with mounting fury, ‘when you get home, I hope Snow White kicks your arse!’

See, the story works just as well without the use of the word ‘dwarf ’, don’t you think? What? Well, whose side are you on anyway? It’s impossible to argue with Billy about such things, but I feel duty-bound to try. ‘I’m calling Peter Jackson,’ I announced. ‘I’m going to suggest he rename your role as “the King of the Little People”.’ Billy ignored this. ‘Did I ever tell you that my granny rescued a child whom she thought was too young to be crossing the road and discovered it was a wee man? Went and grabbed him – scooped him up from the middle of the traffic and gave him a good scolding: “I’ll tan your arse!” she said, before she realized it was a dwarf.’ ‘Billy!’ I cried. ‘LITTLE PERSON! That’s what they wish to be called and we should respect that!’ ‘Now stop it, Pamela,’ he insisted. ‘I’m talking about a dwarf, not a little person. You put a little person and a dwarf together in the same room – they both know which one’s the dwarf!’

I sincerely apologize to any little people who might be reading this. Neither Billy nor I mean to be offensive by the above discussion; it’s never easy trying to navigate the fine, snaky line between comedy and propriety. And, if it’s any consolation, Billy tends to be far more vicious about people his own height – and often for no good reason. I once heard him being ridiculously savage about a perfectly innocuous fellow traveller: ‘What’s he going to do for a face when King Kong wants his arse back?’ he ranted. The man’s crime? Having the temerity to be talking on his cell phone.

To be honest, I have long since given up trying to tame my husband. And anyway, I secretly enjoy his oppositional style, and would probably be lost without the challenge. Yes, he’s wonderfully grumpy (if you like that kind of thing). In fact, he’s ornery about almost everything, including seeing the doctor, informing me of his schedule, or eating anything green with his fish pie. Having said that, he is an excellent cook, with specialities that include great curries, apple pie, and a killer macaroni cheese. He has not touched alcohol for around twenty-eight years, but loves to take a deep whiff of my dinnertime red wine. Billy remains a slim, fish-eating vegetarian with a full head of hair and, just like his grandfather, will probably live to be nearly a hundred. It’s a little scary, though, to imagine an age-indexed increase on the curmudgeonly scale; by his tenth decade his vocabulary of communication may well consist only of frowns, farts, and just one word (yes, that one).

Ten years after this book was first published, the artist is in residence. The man swishing confidently around the bijou Birmingham art gallery – the new home of his latest creative efforts in the form of extraordinary pen drawings – is now formally known as Billy Connolly CBE, visual artist. It’s not exactly a career change, more a career addendum for the Artist Formerly Known only as Billy Connolly, King of Comedy. He’s now both – as well as Master of Mirth, Chancellor of Chortling, Baron of Banjoing and Specialist in the School of Hard Knocks. I confess I also think of him as Commander Curmudgeonly from time to time, as well as Archdeacon of Amnesia. Typically, he has forgotten to tell me about his important first art opening, where a selection of these drawings was to be shown in a small exhibition entitled Born in the Rain. When I finally do learn about this event – on the same day – I’m several hours away in London. I race to Euston for a fast train, and arrive at the gallery just fifteen minutes before the end of the show. I spy Billy just inside the door, a svelte, chic baron in a collarless tweed jacket and a silk scarf covered with butterflies. His hair is cropped shorter than usual for his latest movie. But he’s thrilled by this brand-new role. ‘I’ll be wearing an opera cape and cigarette holder next!’ he says.

I watch Billy, surrounded by people who can’t believe their luck to be standing next to the man. Fortunately, many of them are also art lovers, eager to take home a slice of Billyness to hang in their living rooms. There’s a queue for his stunning drawings and prints, for which he has devised titles such as Extinct Scottish Amphibian, Pantomime Giraffe, Celtic Bling, Chookie Birdie, and A Load of Old Bollocks. He has been working on these for several years now, hunched over his drawing pad for many hours at a time. I especially love the darker, almost sinister ones, such as The Staff, which is a row of similar, expressionless people in gas masks, all facing the same way. Told you it was dark. But as Robert Stoller said, ‘Kitsch is the corpse that’s left when art has lost its anger.’ Throughout the afternoon, Billy tells me, a pointed question has been posed time and time again: ‘What does your psychologist wife think of your drawings?’ ‘Oh,’ replied Billy, ‘she just peers at them then walks away with a superior, shrinky look on her face.’ Rubbish. I take photos of this triumph and text them to our kids. ‘Your father is officially an artist!’ I crow, as if I had anything to do with it. Well, I probably did – especially those pieces that were born of fury or frustration.

Is it ever easy to be with the same person for more than thirty years? Sometimes I think I was not the right wife for Billy. I’m too self-determining, career-oriented, eager for adventure, and busy. Billy might even add ‘bossy’. ‘If you hadn’t been married to me,’ I asked him recently, ‘whom would you have wanted to be your wife instead?’ ‘Sandra Bullock,’ he replied, without a moment’s hesitation. ‘I think she’s lovely. There’s a wee promise in her face. Or maybe Sinéad Cusack, ’cause she’s fanciable, too. And that blonde woman on CSI Miami who looks like you Pamela. Well, she’s OK …’ Billy must have caught my horrified micro-expression, ‘… but she’s not as nice as you …’ Good to know.

Billy was wonderfully supportive when, against his advice, I took part in the BBC television show Strictly Come Dancing. He giggled uncontrollably at my first waltz, but was later caught looking misty-eyed when my dance partner James Jordan performed a routine that helped catapult us to the finals. I wondered if – even slightly hoped – Billy would be jealous of James, but my husband was far too self-assured for that. But he warned me: ‘I wouldn’t trust a man who wore such tight trousers.’ Billy now complains he’s a ‘tango widow’ because I take off after dinner to dance until midnight. ‘Why don’t you come along?’ I frequently ask. Billy has had one tango lesson, and there are black-and-white shoes in his wardrobe, so he is partly equipped for a milonga. ‘Think I’ll give it a miss,’ he says. ‘Watching snake-hipped foreigners molesting you on the dance floor has limited appeal.’

Would Billy have preferred a cosy, soup-maker type of wife? From time to time I’m quite sure he would, but that’s not me. Anyway, he’d hate to have a mate who intruded too much on his daily life. Yes, Billy has become more and more of a hermit. Sometimes I think he’s a budding Howard Hughes. If I visit him in a foreign city where he’s been working for a while I am usually appalled by the state of his hotel room; he just hates letting people in to tidy up. I dare not touch his stuff – his drawing materials carefully laid out, his crossword puzzle beside the bed awaiting inspiration about thirty-two down, his brightly coloured underpants hanging in the shower, his banjo leaning precariously against the bathroom door. I swear he’d let his fingernails and beard grow to disgusting lengths if the various make-up artists he works with did not intervene for professional reasons. He might as well buy some planes, design a bra, and be done with it.

At least Billy and I don’t have a relationship like that of a friend’s grandfather who, when asked how many sugars he liked in his tea, replied irritably: ‘Och, I don’t know. Ask your granny.’ No, we spend too much time apart to become that enmeshed. But despite the travelling both our jobs require, we stay very much in touch. Yesterday afternoon, sitting in New York, I phoned Billy in Manchester. ‘I had the concert of my life tonight,’ he crowed. ‘What exactly made it so?’ I asked. ‘Oh, I just walked on, strode downstage, faced them, and just went for it.’ No one can analyse what Billy does, least of all him. Turned out the crowd at the Manchester Apollo had been treated to a favourite story of mine, about the time he went with a couple of mates to visit a friend in Glasgow. This no-frills bachelor cooked them breakfast, but there were no plates or eating utensils so he proffered food on a spatula. When one of them reacted uncomfortably to being expected to take a hot, dripping egg in his bare hand, he rebuked him with ‘Oh, don’t be so fucking bourgeois!’ Well, that’s the bare bones of the story, but Billy tells it in his idiosyncratic picturepainting style that brings the house down. ‘They loved it,’ he glowed. ‘Of course they did,’ I replied admiringly. ‘And how many times in your life have you felt you’d had the concert of your life?’ ‘About a dozen times,’ he replied. ‘Where?’ I asked, knowing full well I’d never get an exact answer. ‘Don’t know. It’s very difficult to tell. Tonight I was just in great shape with a great audience. Changing my mind. I suddenly thought to tell them about when you’re vomiting having had a curry, you find you’re an expert in African folk music. Then I did a thing about a drunk guy singing. He’s been thrown out of the pub and he’s standing on the street practising ordering drinks. But he gets fed up so he sings a song. Then I sang a new country song I wrote called “I’d Love to Kick the Shit Out of You”.’ See, it doesn’t sound funny when you put it like that, does it? Even Billy himself finds that a problem. He never writes down ‘material’ like most other comedians, but just before a show he tries to think of a list of things he might talk about. This only makes him more scared. ‘I think, “Fuck, I’ve got nothing!”’ he says.