Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

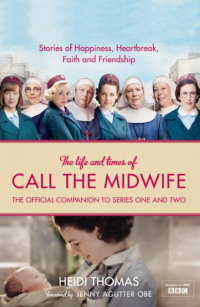

Kitabı oxu: «The Life and Times of Call the Midwife: The Official Companion to Series One and Two»

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

FOREWORD by Jenny Agutter OBE

INTRODUCTION by Heidi Thomas

CHAPTER 1 BIRTH

PROFILES THE NURSES

CHAPTER 2 FASHION

CHAPTER 3 Beauty

Call the Midwife Diaries part 1

CHAPTER 4 FAITH

PROFILES THE NUNS

CHAPTER 5 HEALTH

Call the Midwife Diaries part 2

CHAPTER 6 HOMES

CHAPTER 7 Food

CHAPTER 8 STREET LIFE

CHAPTER 9 MEN

PROFILES THE CHAPS

CHAPTER 10 CHRISTMAS

Call the Midwife Diaries part 3

CAST LIST

THE ARCHITECTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

FOREWORD

JENNY AGUTTER OBE

I was born in Somerset in the 1950s. My father told me recently that he was present at my birth, but as men were not allowed into the delivery room at the time it was more likely that I had arrived, been cleaned up, and presented to him as a neat mewling bundle. Although my parents did not share the same faith, they gave me a religious upbringing. Decades later my son was born on Christmas Day, which meant I had shifts of midwives attend his birth. I thought I knew about the period, religion and midwives and would be well prepared to play Sister Julienne in Call the Midwife, but I had a lot to learn.

Time was set aside before filming the first series to learn how to appear adept at being midwives, particularly at handling newborn babies. Serendipitously, I met the real-life Julienne’s niece, who gave me valuable insight into her aunt’s personality and lent me some of her drawings and letters. She was a talented amateur watercolourist who always found time to send painted cards and notes to family and friends, never forgetting an anniversary or birthday. I discovered a deceptively strong-willed woman with a great sense of humour who enjoyed people with all their faults, always finding the best in them.

The more I discover about the nuns who worked in the East End, the more my respect grows for these women whose faith gives them an unquestioning sense of purpose. They served their community, particularly the women, at the most vulnerable and intimate time in their lives. Childbirth is always a miracle and midwives are indeed unsung heroes.

My parents went out of their way to make sure that my brother and I were not burdened with any of the concerns and fears they had grown up with. We owe so much to the indomitable spirit of those who lived through the turmoil of war, and worked hard to rebuild our world. The squalid and poverty-stricken area of Poplar and London’s docklands was heavily bombed and there was no money to repair the excessive damage or to re-house the many families who had lost their homes. Subsequently, the tenements that should have been torn down and rebuilt remained occupied and overcrowded.

Because many of the characters in Call the Midwife are based on real people who lived and worked in the East End, all the cast feel a keen responsibility to serve them well. They are vividly depicted by Jennifer Worth in her bestselling memoirs, and brilliantly shaped for the series by Heidi Thomas, and have been a pleasure to get to know and play. You always hope that an audience will enjoy work that you feel proud of. I was delighted and amazed by the diverse audience we reached and find myself being stopped by people of all ages and backgrounds who want to let me know how the series has affected them.

Costumes and set design play a vital part in creating the mood and helping the actor believe in what they are doing. The creative team working behind the scenes on Call the Midwife have captured the period meticulously, paying attention to every detail. As well as sourcing and recreating the furnishings of the time, the production team found small personal items from the fifties with which to adorn tables, cupboards and fireplaces: books filled with savings stamps, old postcards, magazines to inspire the homemaker with advertisements featuring women, neat and feminine with their narrow waists and big skirts, seemingly unaware of the changes that were beginning to give women an equal place in society. Each chapter of this book reveals just how this flawless attention to detail was brought to life.

Working on the series has given me an insight into the extraordinary decade that followed the war, shown me what faith is capable of, and given me the chance to better understand the delicate and under-praised work of the midwife. It has been an exciting adventure, one I am honoured to be able to share.

INTRODUCTION

HEIDI THOMAS

(© Cath Harries)

First encounters always linger in the mind. The older I get, the more I appreciate the way the mind seems to take a mental snapshot of the moment. I can still envisage the first time I walked through the doors of my grammar school, the first time I saw my husband, the first time I clapped eyes on my baby’s face.

I was initially approached about the book by Pippa Harris of Neal Street Productions, who believed the memoirs of the then unknown Jennifer Worth might have potential as a television series. I was not – I am ashamed to say – especially intrigued. Fresh from the joyful experience of writing the BBC classic serial Cranford, I was passionate about finding new books to adapt, but didn’t think this would fit the bill in any way. It was not set in my favourite century (the 19th) and, even more importantly, its author was alive and well and living in Hemel Hempstead.

Adapting another writer’s work for the screen is a fraught and delicate business – changes are inevitable, and I have a keen conscience. I shudder at the thought of causing distress or offence to the person whose imagination, hard work and talent have brought a book about. While I was writing the scripts for Cranford, sometimes the only thing that kept me going was the thought that Mrs Gaskell had been dead for many decades. Meanwhile, Jennifer was not only still with us, but had based Call the Midwife on her own, deeply personal experience of working in the East End in the 1950s. I imagined that even the smallest details would be important to her, and that any alterations might prove painful.

‘No,’ I said to Pippa, ‘I don’t think it’s for me.’ Pippa didn’t listen. She and I have known each other for many years, having worked on our very first television job together – the series Soldier, Soldier – in the 1990s and there was a touch of stuff-and-nonsense in her tone.

‘Just read it,’ she said. ‘I know you, and I know you won’t be able to put it down.’

‘But it’s set in the 1950s!’ I replied, rather weakly. ‘It’s not historical, and it’s not modern either. It just won’t be my cup of tea – I want to do another Gaskell, or a Dickens.’

Pippa sent it to me anyway. I read it, and she was right – I couldn’t put it down until I’d finished. I can still recall the weight of it in my hands (this was the early, hardback edition) and the way my wrists ached as I compulsively turned page after page. It was my first encounter with the magic of Call the Midwife, and I will remember it all my days: the first sighting of the youthful Jenny Lee, picking her wasp-waisted way through the bomb sites of Poplar; the first batty utterance from Sister Monica Joan; the first time Chummy tumbled from her bike.

Over and over again, I was surprised and delighted by the characters, the stories and the sheer muscular vigour of Jennifer’s writing. I have never been sure whether I devoured the book, or the book devoured me, but by the time I closed it and crawled into bed, the die was cast: I was on board, and wouldn’t rest until I had brought Call the Midwife to the screen.

Looking back, I actually made that decision when reading page thirteen. I know this because my original copy of the book still sits on my desk, and I can see that on page thirteen I underlined a single sentence in pencil, and wrote one word in the margin alongside it. That word is ‘YES’, and it marked the first time Call the Midwife made me cry. In the middle of a crisp, factual description of childbirth in a working-class London home in the 1950s, Jennifer had dropped one beautiful comment that transcended all barriers of geography, class and time. It was this:

‘How much more can she bear, how much can any woman bear?’

Those words went straight to my heart. Here, at last, was a book that told the unflinching truth about an experience that defines the lives of women the world over, and has done so for countless generations. Furthermore, birth is something that happens to us all. We must all be born, just as we all must die. It is the one common miracle, an experience that unleashes every emotion we possess. As a midwife, Jennifer understood this more than most, and by setting down her memoirs, she shone an unprecedented light on her own profession.

In turning the books into a television series, it became my privilege to continue the work that Jennifer started. Much laughter was had – and many more tears shed – as the show evolved.

Getting a TV drama to the screen is always something of a journey. As the writer, I travelled alone at the outset. But Call the Midwife rattled onwards, a bit like a train, stopping to pick up people along the way. Producers, designers and directors came aboard. As filming approached, we were joined by actors, technicians and composers. There were babies in the mix, and medics to advise us. The challenges were legion, but we were a happy band, and this book is our attempt to share the graft, grind and sheer exhilarating joy of going back to the 1950s to make the show we loved so much.

As I write these lines, the cameras are about to start turning on the second series of Call the Midwife. Jennifer Worth died two weeks before we had begun to film the first. She would call me sentimental for this, but I find it impossible not to picture her standing alone on a railway platform, having got off the train several stations too soon.

Ours was an unusual friendship. Jennifer was bossy and I am stubborn, so it could have been a disaster. When we were first introduced, each of us was quite rightly nervous of the other. But in that rare way that happens when minds truly meet, we soon bypassed all the niceties and joined forces. That was that; we were in it together. And we still are.

On my desk, tucked into my very first copy of Call the Midwife, is the final letter Jennifer wrote to me. It contains some thoughts on the last script she was well enough to read. She ends, in her elegant spidery hand, with the words, ‘I leave it to you with confidence.’

But Call the Midwife is not mine, and I do believe that deep down Jennifer never really felt that it was wholly hers either. She always insisted that, in the books, she was simply bearing witness to the lives of others. In writing the television series, I followed her example and tried to do the same. Because birth is in the possession of humanity itself, and from our very first breath, these are stories we all share.

CHAPTER

1

BIRTH

BIRTH

‘I DON’T WANT AN ENEMA. IT’S NOT DIGNIFIED!’

MURIEL

‘IF YOU WERE THAT KEEN ON YOUR DIGNITY, YOU WOULDN’T BE HERE NOW.’

MRS HAWKES

Everybody has a birth story, whether it is known to them or not. I was – by coincidence – brought into the world by nuns, in a small private hospital in Liverpool. The delivery was notable only for its speed. But whenever a woman visits a newly delivered relative or friend, the talk swiftly shifts from the baby to the labour: ‘How was it?’ we whisper. And the details are divulged and sympathised with – and will be told, and told again, in years to come. Tales such as these – ordinary, homespun, heartfelt – are the lifeblood of every Call the Midwife episode. And that is as it should be, for each arrival in this world is totally enthralling, a repeat beat of the greatest story ever told.

Many of the births we feature are unusual by definition. In the first series, for example, we saw the birth of triplets to an unmarried mother living in a derelict flat. Lacking even a blanket for the third child, Chummy, played by Miranda Hart, stripped down to her petticoat and wrapped him in her nurse’s uniform. In another episode, she carried out a breech delivery alone, coaxing a petrified mother through the slow, controlled descent of the infant’s feet and legs.

But we wanted our first birth to be an ordinary one – raw, uncomplicated, intimate, exhilarating. We wanted the fifties’ trappings of the enema and shave, and the regulation left-hand-side delivery position. Above all else, however, we wanted to make it timeless, immediate and real. And so, in the opening episode of the series, ordinary unexceptional Muriel, attended by her mother, Sister Evangelina and newcomer Jenny Lee, gave birth to a boy without any complications or much fuss. It was a birth like hundreds of thousands before it, and hundreds of thousands to come – and therein lies its power.

As Pippa Harris, executive producer of Call the Midwife, comments, ‘There is something completely universal about birth; it touches us all. You don’t have to be a mother or even a woman to engage with it. All humans are drawn to it, time and again.’ Mulling over the huge success of the series, she adds, ‘The stakes are just so high; at any point the outcome can switch from one of joy to terrible sadness. Birth is inherently dramatic.’

No one who works on the show is more acutely tuned to the miracle of birth than Terri Coates, a midwife and lecturer of some thirty years standing. Terri, our peerless consultant midwife, has been involved with Call the Midwife from the start.

Terri first encountered Jennifer Worth after publishing an article in a midwifery magazine a dozen years ago, lamenting that midwives were ‘almost invisible’ in literature. ‘Maybe,’ wrote Terri, ‘there is a midwife somewhere who can do for midwifery what James Herriot did for veterinary practice?’

Among many responses, Terri received a letter from retired nurse Jennifer, who said the article had inspired her to write her memoirs. Some 18 months later, she wrote again, having completed them. Terri offered to read the manuscript and was duly sent it – to her surprise, it had been written by hand on an odd assortment of pages, which she describes as being ‘rather difficult to keep in order.’

‘It was a lovely story about women, and for women, and it was very powerful.’ Terri suggested to Jennifer that she might be able to correct some clinical errors in the text, and Jennifer – who had practised long ago and for only seven years – accepted the offer. A long and collaborative relationship ensued and, once I began to write the series, I too turned to Terri for support.

Hailed as a ‘baby whisperer’ by awestruck technicians, Terri is modest about her talents.

‘I don’t think babies are at all fazed by being on set. If you hold a newborn confidently they tend to relax and calm down very quickly.’

In fact, Terri admits she is more likely to cry than the babies, having been routinely reduced to weeping during filming. What’s more, she isn’t alone.

Philippa Lowthorpe, principal director of Call the Midwife, confesses: ‘When we filmed our first birth scene – the traumatic arrival of Conchita Warren’s desperately premature baby – it was such an intense experience. The film crew, Terri and I were moved to tears.’ For male and female witnesses alike, all birthing scenes have proved emotional. Philippa adds, ‘I have two children myself, so I should be used to it, but there is something so powerful and profound about showing a new life coming into the world, often in difficult circumstances. And, of course, these women gave birth at home, with virtually no pain relief.’

Sometimes it seems the only people on set who aren’t crying in the birth scenes are the babies. Tenderly nursed by Terri, and with everyone walking on tiptoe, they often sleep deeply throughout their time on camera – which isn’t necessarily what the script requires!

In real life most healthy babies are wakeful at the point of birth, and it’s great to capture open eyes and flailing, starfish hands. However, we would never, ever do anything to unsettle a contented babe and the crew are adept at working round unscheduled naps. Terri occasionally sanctions gently blowing on a dozing baby’s cheek, or softly tickling their feet, but if this doesn’t work shots are angled so the face cannot be seen. The sound of crying – carefully recorded when it spontaneously occurs – can then be dubbed on afterwards. In addition, I usually have some emergency dialogue scribbled down so that if I am phoned from the set with the panicky message, ‘It’s absolutely FAST asleep!’, I can supply one of the adult actors with some explanatory lines.

Newborn babies tend not to be on the books of modelling agencies, so we recruit them direct from the maternity wings of local hospitals. During the first series, Call the Midwife was unknown to the masses, and we sometimes struggled to explain what we were up to. Second time around we have been bombarded, with some expectant mothers calling us direct and e-mailing photographs. Nobody has actually sent us their scan pictures yet, but it’s only a matter of time.

The younger the infant, the better. In an ideal world, our babies would not be more than four days old, when they still have the glazed and curled-up look of the newly born. However, they must be licensed by their local council before they can appear on screen, and this protective procedure takes at least a week. Second assistant director, Ben Rogers, and his team try to get one step ahead by booking babies in advance of their due date, but Mother Nature has no respect for filming schedules. We are often undone by them arriving early or too late.

Despite the nightmarish booking process, the presence of a baby brings about a tingling hush that makes the day’s work special. As Pam Ferris, who plays Sister Evangelina, observes, ‘It changes the atmosphere completely, you can sense something extraordinary in the air.’

Babies can ‘work’ for no more than twenty minutes at a time. There is more leeway with twins, who can be used alternately, but these are seldom available to us. Terri ensures that the tiny stars are held properly, kept warm and that the surroundings are clean and hazard free. She is often contorted – out of sight of the cameras – beneath or behind the bed so as to stay within instant reach of the baby.

Natalie Hannington signed up her tiny daughter Santana – her sixth child – after seeing one of our leaflets in her maternity clinic. An eight-pound baby, Santana arrived via Caesarean section. Natalie, who is 31, describes her as ‘just perfect’, and was happy to share her baby with the nation on the screen.

Before appearing on camera Santana, like all performers, made a visit to make-up. There, she was massaged with pure grapeseed oil and ‘bloodied’ with a sugar-based red colouring so that she looked fresh from the womb. Many babies are also born with a coating of vernix – the white fatty substance that protects their skin in utero – and if this is required, a paste of Sudocreme and oil is carefully applied.

Christine Walmesley-Cotham, hair and make-up designer, supervises all of these preparations. Responsible for many blood-and-gore effects across the series, she is deeply involved in making pregnancy and birth look real on camera.

Christine says she is grateful that, since the advent of silicone, medical prosthetics are of a universally high quality. This lightweight malleable material offers a durability and level of detail that was not possible with latex. Silicone is used to create bumps for ‘mums-to-be’, which can be padded to suit the stage of a fictional pregnancy, and coloured to match the skin tone of the actress. My own favourite prostheses, however, are the exquisitely delicate umbilical cords – small coiled masterpieces of palest mauve. It seems at once odd and entirely right that they should be kept in the make-up store, alongside the lipsticks and lacquer. For these are props from the world of women, things that are stored in the vault of all we share.

When it was time to film Santana’s scene, real-life mum Natalie watched proceedings on a monitor. The baby murmured only briefly, when she was first carried into the bright light of the set, but settled within moments. Helen George, who plays Trixie, handed her to the actress playing her mother, who cradled her lovingly, and after Philippa called ‘Cut!’ there was the usual sound of all the male technicians clearing their throats and blowing their noses.

‘It was weird to see her handed to someone else,’ admits Natalie. ‘But it’s lovely just looking at her. It would have been fantastic to have done the same with all the other children,’ she says. Like every mother who has taken part in the show, she will keep a recording of Santana’s TV debut for the young star to see when she is older.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.