Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Rat Pack Confidential»

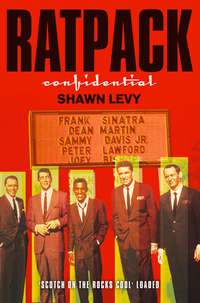

RAT PACK CONFIDENTIAL

SHAWN LEVY

Frank, Dean, Sammy, Peter, Joey & the Last Great Showbiz Party

Dedication

For my mom, Mickie Levy, who arranged for me to see Frank at the 500 Club when I was still in Utero …

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part 1

Part 2

Slacksey o’brien

105 percent

Sonny boy

America’s quest

I was told to come here

I‘m not going to stooge for anyone

Part 3

Much, much, much

Some things you don’t want to know

The only singer

Worthless bums and whores

The place was on fire

Almost the end of frankie-boy

The most exciting assignment of my life

What they were really being paid for

What we do is a rib

I feel dirty

I’m a whore for my music

The Frank situation

One of these days it’ll come out

You and I will always be friends

It always ended up as a threat

He’s needed this for years

Say goodbye

Part 4

I’ve got five good years left

I don’t know what hit me

‘Scuse me while I disappear

I wanna go home

Part 5

Not a moment too soon

Adult male human behavior

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part 1

This was Frank’s baby.

Onstage, Dean, singing almost straight, then pissing away anything like real feeling with jokes.

In the wings, Sammy, Peter, Joey.

Out front, a mob scene: Marilyn, Little Caesar, Kirk, Shirl, Mr. Benny, that Swedish kid that Sammy was so crazy for, that senator and his tubby kid brother, a few broads without addresses, a few guys without real names …

Famous faces at ringside for the cameras, infamous ones in the shadows in the back, plus a hundred or so civilians as bait for the rest of the world—suckers with money to blow and dames to blow it with them until it ran out.

In the casino, every schmuck that couldn’t pay or beg or muscle his way in was betting his rent money just to feel as big as the ones who could.

The joint was packed; the rest of town might as well have been dark.

And for what?

A movie, a party, a floating crap game, a day’s work, a hustle, a joke: They’d make millions and all they had to do was show up, have a good time, pretend to give a damn, and, almost as an afterthought, sing.

Sometimes it seemed like Dean had the right idea: “You wanna hear the whole song, buy the record …”

But there was something in the music, wasn’t there? With the right band and the right number, it was like flying—and like you could drag everybody up there with you.

So let Dean do jokes, and Sammy—Sammy would start numbers and they’d stomp all over them and he’d like it.

But when Frank sang, it would be straight. It could be New Year’s Eve, the very stroke of midnight, the middle of Times Square, and he would stop time, stop their hearts beating, and remind them where the power was.

It was in his voice.

It was his.

When they finally had enough and dropped the curtain, they would wander out into the casino.

Some act’d be up there on the little stage in the lounge, and maybe they’d go over and screw around; Sammy liked that the best—more eyes on him, always more eyes.

What Dean and Frank liked was dealing. They had points in the joint, and who was gonna stop them from horsing around at a table: It was their money, right?

Dean actually knew what he was doing. He’d push aside a blackjack dealer and do a little fancy shuffling and start dealing around the layout: his rules.

“You got five? You hold. That’s a winner.

“Nineteen? Hit. Twenty-six? Another winner.”

He’d shovel out chips and make sure that everyone took care of the real dealer, who’d stand there looking nervous over at big Carl Cohen, the casino manager, who normally didn’t go for clowning.

But Carl would be quiet. He’d lose a couple hundred during this monkey show, sure, but he’d get it all back and more: There were crowds five or ten deep just waiting to get at the tables. Besides, Dean was like family; he’d worked sneak joints back in Ohio before the war with Carl’s kid brother. The big guy could afford to be a little bit indulgent.

Which wasn’t the case with Lewis Milestone, the poor director saddled with making a movie in the middle of it. Every morning he came to work in an amusement park that his boss owned and woke his boss up and tried to get him to jump through hoops for a few hours, and you had to look deep into his dark old eyes to see what he really thought about it.

This movie wasn’t some work of art, this wasn’t All Quiet on the Western Front with poetic butterflies and mud and a moral. This was a sure thing, a money machine, a way to bring the party to the people who could only read about it in the papers. Hell, the only reason they hired him in the first place was that Jack Warner insisted on a pro and Peter guaranteed that the old guy—who was making Lassie shows, for chrissakes—would do whatever they told him.

But, still, they didn’t want to make a career out of it. So come the morning, they let Millie run them around in circles for a little bit, even if they hadn’t gone to sleep yet on account of last night was, as they liked to say, a gasser.

Or at least everyone but Frank let him do it. Frank was the boss, after all, and picture or no picture, he was going to work when he felt like it. He used to say that he only had one take in him, like he was an artist about it. The truth was he only had one take he gave a shit about, and if they wanted that one in the movie, then they’d have to wait until he was ready to give it.

So Sammy, a Salty Dog or two down the hatch, would show up on the set at 9:00 or 10:00 in the morning, and Dean and Peter would show up at 9:00 or 10:00 in the morning, and Joey—who was lucky to be here at all, let’s face it—would be there at 7:00 or whenever they said so, showered and alert.

But Frank: 4:30 in the afternoon, maybe 5:00; and twice, twice, before lunch; and most days not at all.

They worked on the picture twenty-five days in Vegas; Frank showed up nine.

Oh, it was his show, all right.

In the early evenings, between a few hours of the movie and going back out onstage, the steam room. Frank had it built—the first one on the Strip—and when he was in town it was off limits to anyone else. They’d drink in there and make phone calls and give each other the needle: the only time they could all be together and alone.

Some other people were allowed in: the ultimate VIP room. This Rickles would take these incredible liberties with Frank and Frank would kill himself. Sammy would take one humiliation after another—“You can’t wear a white towel. Here’s a brown towel for you!”—and act like he was killing himself. Actors from the movie. Business guys. Other guys who didn’t say who they were. This was an inner inner circle. Men capable of all sorts of acts of power would sit like convent girls just for the pleasure of having been allowed inside. Compared to this, the show and the movie were, well, for anyone.

But not just anyone was welcome. This was a group that Frank handpicked, gliding through the world, sizing people up, then giving them the golden tap on the shoulder and bringing them in.

Talent, money, power: None of these was quite enough. You had to have something Frank had, or something that he wanted to have more of. You were a cool, leonine Italian, or a dazzling black ball of fire, or a British sophisticate with powerful relatives, or a Jewish wiseguy who could brush off the world with a shrug. You were an Irish millionaire senator or a psychotic Mafia lord. You were the acme, the original, one of a kind, and Frank wanted you up close to study. He gathered everyone around him and sat in the middle and saw little parts of himself, little things he could fix or steal—Dr. Frankenstein building a hip new kind of superman.

Frankenstein, though, or Nosferatu? Because, though everyone got rich, got famous, got laid, Frank got more. They made movies; Frank was the producer. They cut records; Frank owned the company. They played Vegas and Tahoe; it was Frank’s hotel. Everyone did good work; Frank was Michelangelo.

They called him the Leader; they asked him to be their best man; they named their kids after him, their daughters, even. And when it all spun out of control, when the precious, delicate balance came undone, when the merry-go-round stopped with a jerk, everyone got thrown on their ass—or worse—except Frank, who stood there in the middle, unfazed.

Divorce, drugs, bankruptcy, death, irrelevancy: Every single one of them took a major hit.

Frank didn’t get so much as a scratch.

But that would all be later. That would be after the golden time, when, for a while, no matter what they did, it would sell. No matter how many broads, no matter how much booze, no matter who they got mad at or cozied up to, it had reached a point where Frank could simply do no wrong.

The press knew the story. They didn’t write it, but they knew it. They didn’t rat him out because they needed him more than he needed them, and except for a few he’d chosen as whipping boys, they lined up to do whatever he wanted them to do.

He was drinking with this one or that one or fucking this one or that one—who was gonna talk?

And anyone he wanted around him, the same thing: You hiding from the G? You don’t need to hide around Frank. You got a wife back home who reads the gossip page? Frank’ll see that you’re not in it. You running for president? Frank’ll throw a little juice your way and make sure everything looks on the up-and-up.

Up close, the whole thing was not to be believed. You wanna talk about rebellion? Those rock ’n’ roll punks had no idea what a real rebel did in private. They couldn’t begin to understand the power and the appetites and how little you had to care. La Dolce Vita nothing: This bunch made Nero look like a Cub Scout.

But outside, from far away, it didn’t look like ego or license or indulgence. It looked like a big, beautiful party in the desert, with laughs and music and cars and clothes and incredible women, and no one ever ran out of money, and no one ever got tired, and no one had to answer to anyone, and no one ever grew old, and you would just die unless you could be there—even if the closest you ever got was a movie theater or a record player.

Wherever they went, they drew a crowd. And not just yokels, but Friars and sex symbols and made men and the president himself. They made Vegas Vegas, Miami Miami, and Palm Springs Palm Springs. And they made and broke people like they were pieces of toast.

For a while, everything took a backseat. For a while, the whole world was like a gyroscope, spinning so fast that it looked like it was standing still, with Frank and his cronies smack-dab in the middle of it, smiling at you, making you think you could do anything.

The world wasn’t big enough for them to bother with so they made it bigger and took it over.

And instead of resenting it, people loved it.

And there was never anything like it before or since.

Between 1957, when his hero Humphrey Bogart died, and 1963, when his friend Jack Kennedy died, Frank Sinatra was the biggest star in all of showbiz.

There was Elvis, of course, and John Wayne and Danny Thomas and Ray Charles and Marlon Brando and Bob Hope and Pat Boone and Tony Curtis and Frankie Avalon and Jerry Lewis and a whole lot of other people who were Kings of Pop, or certain quadrants of it, at the time.

But nobody was so sheerly supreme as Frank as an icon, artist, or draw, none held his mighty sway over the mass imagination, and none was so ascendant for so long.

With his stunning LPs for Capitol Records—Songs for Siwingin’ Lovers, In the Wee Small Hours, Come Fly with Me, Only the Lonely, a good dozen more—he was releasing classics at the rate of several a year and moving big numbers in the record stores.

With a string of commercial hit movies—and good ones, frequently, like The Man with the Golden Arm, The Joker is Wild, High Society, and the Oscar-winning From Here to Eternity—he ranked among the era’s top-grossing movie stars.

He had regular specials on television (though rarely very good, they always drew well); he was the top act in nightclubs from Miami to Chicago to Las Vegas; he performed with ceremonious duty at charity events, Academy Award telecasts—all the orthodox showbiz sacraments.

Arguably no single entertainer had ever held the top spot in so many media for so long—Bing Crosby, maybe, back in radio days.

No, Frank was It.

And It in ways that nobody ever had been.

Because as big a deal to the popular American mind as Frank’s considerable musical and cinematic lives was his private life.

Flitting from gorgeous bedmate to gorgeous bedmate, rubbing elbows with tough guys, throwing punches, pounding back whiskey, romancing in a cigarette’s glow, he was the envy of every American male who had left off worshiping Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams for more grown-up pursuits: the rakish kid brother-in-law they’d all secretly give their left arms to trade places with.

There was nothing, it seemed to the average working stiff, that Frank didn’t have.

But Frankie—and who could have guessed it?—didn’t like to be by himself: He got antsy. He liked to have entourages of like-minded he-men around him, guys to drink and schmooze and play cards and go to the fights and hit the bars with: chums.

He wanted an accumulation of bosom fellows around him, and he thought it would be wonderful if they could work together. He began to play with his buddies in nightclubs, to make films with them, to pop in on their TV shows and invite them onto his.

He started smallish—a picture with one or two here, a spontaneous walk-on there—but then his horizons expanded. Various threads in his personal and professional lives began to merge in ways that no one would ever have predicted: his affectations toward politics and the Mafia, for instance, his ownership of film and record companies and shares in casinos, his friends and debtors and vassals.

At the end of 1959, he concocted an intoxicating brew of money, power, talent, romance, gall, a nexus of showbiz and muscle, politics and glamour, a brilliant netherworld spinning at 33⅓ with himself stock-still at the center, conducting it all with his mind.

They alit in Las Vegas for a month to make a movie and play a historic nightclub gig that they called the Summit; they hit Miami, the Utah desert, Palm Springs, Chicago, Atlantic City, Beverly Hills, Hollywood back lots, illegal gambling dens, saloons, yachts, private jets, the White House itself.

It was what a good portion of America was about for a few remarkable years.

It was sauce and vinegar and eau de cologne and sour mash whiskey and gin and smoke and perfume and silk and neon and skinny lapels and tail fins and rockets to the sky.

It was swinging and sighing and being a sharpie, it was cutting a figure and digging a scene.

It was Frank and Sammy Davis Jr. and Dean Martin and Peter Lawford for a while and Joey Bishop when they asked him and Jack Kennedy and Sam Giancana and tables full of cronies and who knew how many broads.

It was the ultimate spasm of traditional showbiz—both the last and the most of its kind.

It was the high point of their lives and a midlife crisis.

It was the acme of the American Century and a venal, rancid, ugly sham.

It was the Rat Pack.

It was beautiful.

Part 2

Slacksey o’brien

Grow up with immigrant parents and a last name that no one can pronounce right, with an ear mangled by a midwife’s forceps and no meat on your slight bones, with no brothers or sisters, and a mother always on the go, and a queer little dream that you can win the whole world over with a song; grow up with all this, and then win wealth and fame and acclaim and power—the whole world and more—and you’ll likely find no embarrassment in living as if your every action was the stuff of legend.

Throughout his life, Frank would be boosted in his perception that his progress through the world was of great import, and if he ever lapsed into doubt, there would always be someone around to reassure him: a wife, a dame, a publicist, a thumbbreaker, a daughter, a fan, even, though not quite so reliably, the press. Frank could count on being spiffed-up, spoiled, spirited out of jams; he expected it of life. And it was an expectation born not in the flush of his success but in the earliest days of his youth: Of all the hangers-on, sycophants, yes-men, and boosters, his mother was first and foremost.

There was undeniable steel in Natalie Garavante, the little pug-faced Genoese firebrand known to everyone in Guinea Town, Hoboken, as Dolly. She prodded the men around her to let her through doors that she herself would’ve battered down in a world that cut women an even break. She had a stunningly foul mouth: “Her favorite expression was ‘son of a bitch bastard,’” recalled a mayor of Hoboken who knew her in his youth; a mob lawyer who met her in the 1960s compared her way with profanity favorably to Jimmy Hoffa’s. She made the slow-moving Italian men around her jump at her command, and she carried enough clout to get political bosses and city officials to do the same. She was a shit-stirrer and a hollerer; she worked hard and she took no prisoners; she spoke simpatico with the people in the streets and defied the men of power. If she’d’ve been born a boy, she might’ve been an Italo-American Huey Long.

But she was a woman and it was the 1910s—and an Italian neighborhood at that—and so she had to find a husband, and she settled on a handsome, illiterate kid from the neighborhood, a guy who couldn’t hold a steady job but cut a dashing figure in the boxing ring. Dolly’s brothers were boxers, which was probably how she came to meet Marty O’Brien, a stout, quiet little guy with tattoos on his arms. Maybe she first took him for Irish, which would’ve appealed to her social-climbing instincts; soon enough, she learned he wasn’t an O’Brien but a Sinatra, but that didn’t make him any less attractive. He might’ve been an unfinished project, but Dolly was sure she could make something of him. Despite her parents’ fears of a layabout Sicilian for a son-in-law, they eloped and married in a civil ceremony. A year and a half later, she bore their first and only child.

Later on, he would try to depict himself as some kind of Dead End Kid turned good, but the truth was that Frank was always plushly seen to. In a neighborhood where the men worked menial jobs and the women raised broods of five, eight, ten brats, only-child Frank had two working parents and a surfeit of candy, toys, bikes, clothes. The homes in which he grew up were the finest to which Italians in Hoboken could aspire. A lot of the Sinatras’ neighbors on the tony streets on which they lived didn’t even know they were Italian: Marty ran a popular speakeasy under his boxing name, and Dolly routinely introduced herself as Mrs. O’Brien; when Frank’s buddies wanted to tease him about his Little Lord Fauntleroy wardrobe—he had his own charge account at Geismer’s department store—-they dubbed him Slacksey O’Brien. They were a family on the rise; a local newspaper society page reported on a New Year’s Eve party Dolly threw after they bought a grand home at the height of the Depression.

By then, Frank had revealed himself as a perfect mix of his parents’ temperaments. Hotheaded and ambitious on the one hand, he liked to loaf and schmooze and was an indifferent student on the other. For all that he inherited from his parents, he was, typically, embarrassed by them as well. Marty was no world-beater, everybody knew that, and he seemed pronouncedly meek even among his friends and colleagues; Dolly was outrageous, flamboyant, earthy, loud, an unignorable commotion whose affectations and ambitions grated on as many people as they inspired. Worse yet, she was the neighborhood abortionist, known to all the Italian girls as the person to turn to when they were in trouble; Frank’s ears would turn red whenever he heard people talk about his mother the “rabbit catcher.” Like everyone else, he was attracted to Dolly’s exuberance, but like Marty and the other men in the family, he feared her. “She was a pisser,” he’d say later, “but she scared the shit outta me. Never knew what she’d hate that I’d do.”

As if to erase the shame Dolly put him through—the dudish threads, the mortifying secret work, the rowdy spectacle she made of herself on nights out with the girls—Frank seemed, at first, to take after Marty. He dropped out of school; he couldn’t keep even a menial job; and he took up a fancy even less promising than Marty’s boxing: Smitten with Bing Crosby, he wanted to be a singer.

At the sight of her boy sporting a yachting cap and crooning in a mirror, Dolly was, as her parents had been by Marty, disgusted, but the idea of denying her boy something that he wanted was worse. She bought him a spiffy electric P.A. system and convinced acquaintances to let him sing in their saloons and restaurants; eventually, she used her clout to get him a job chauffeuring a rising local trio, the Three Flashes, who were preparing to make a few movie shorts for Major Bowes, the era’s great promoter of amateur showbiz talent; with his mom’s backing, Frank quickly rose from driver to jester to full-fledged singer in the group.

The older guys in the act, which Bowes redubbed the Hoboken Four, didn’t care much for the mama’s boy in the midst, even less so when Frank’s singing improved and his solos became a centerpiece of the show. During a several-month nationwide tour as part of one of Bowes’s traveling road shows, they began picking on the skinny kid, beating him up when they felt he needed to be taken down a peg. Frank quit and returned to Hoboken—where Dolly had salted the press with news of his successes.

Three years of scattered, aimless work followed, then a steady job—singing waiter at the Rustic Cabin in Englewood Cliffs, a roadhouse which had a broadcast wire to New York’s powerful WNEW radio station. In June 1939, bandleader Harry James heard Frank on the radio and drove out to see whose voice that was. Shazam: Frank was in. James signed him, they hit the road and cut some records, and Frank got a little bit of notice. In December, Tommy Dorsey auditioned him and he left James with a handclasp and best wishes.

This wasn’t just the call of Lady Luck or the reward of sheer ambition. Somewhere sometime in there, a miracle bloomed. Frank’s voice went from pleasant to stunning: a beautiful, tender instrument possessed of uncanny rhythmic sense and breath control, one of the great talents of the century, a gift no more explicable than those of Joyce and Picasso, recognizable as such even in its juvenile state. Everyone who heard him for the first time was staggered.

As a member of the Dorsey orchestra, Frank became famous: hit records, magazine covers, appearances in movies, flattering press. Like he’d learned from Dolly, he milked it, aggressively courting the press, disc jockeys, anyone he thought could boost his career. He spent more than he earned on his wardrobe alone (he was so finicky about his personal cleanliness that his bandmates with Dorsey nicknamed him Lady Macbeth). Within three years, he was convinced that Dorsey was holding him back from a career that would rival Crosby’s, and he left—after months of bitter, petty infighting, a lucrative settlement, and a grudging goodbye.

Suddenly, everything: Frank signed to play the Paramount Theater in Times Square as an “extra added attraction” with the popular Benny Goodman orchestra; when Goodman introduced Frank, the response from the packed theater was so volcanic that he asked his band, “What the fuck was that?” Within a few months, the whole world would know. Spontaneously, Frank had become the beloved of a generation of wild-eyed fans—young girls, mostly—who made him a teen idol decades before anyone ever thought to manufacture such a thing.

Boosted by the devilishly clever press agent George Evans, Frank became bigger than Crosby or Vallee or Caruso—the biggest thing ever in showbiz, in fact. There was a core of critics and musicians among the cognoscenti who admired his artistry (James Agee spoke fondly of his “weird, fleeting resemblances to Lincoln”), but the wellspring was the kids—the bobby-soxers, as they were named for an affectation of footwear. Sinatratics they called themselves, forming cultish cells in devotion to their new god: the Slaves of Sinatra, the Sighing Society of Sinatra Swooners, the Flatbush Girls Who Would Lay Down Their Lives for Frank Sinatra, the Frank Sinatra Fan and Mahjong Club.

These daughters of flappers were quick to connect the longing in Frank’s voice with their own longings, his quavery presence with the absent boys who were off fighting the Hun and the Nip (Frank was 4-F: punctured eardrum). Odd as it may have seemed to everyone in the business, the wiseass runt with the heavenly voice was some kind of sex symbol. (And he’d always be one: For a half-century, Frank was one of the ways America made love, quite often the most popular; he was able to get away with anything because he hit people in their most personal spots.)

By the late fifties, by Rat Pack time, when his audience had grown up, Frank could be as sexy as he felt, but in the first blush of his fame, he had, like all teen idols, to be officially Off Limits. Conveniently, he had a cozy domestic life to play up: He’d been married to a girl-next-door type since 1939; by 1944, they had two kids, one named after each of them: Little Nancy and Frankie Jr.

For George Evans—and for Frank’s many important employers: Columbia Records, CBS radio, MGM, Lucky Strike—this was a perfect setup: a talented, massively popular young guy with a solid family and a wholesome aspect. But Frank seemed hell-bent on screwing it up. There was that entourage—big, unlikely guys, boxing writers, gamblers, songwriters buttering him up—and there were women and there was this habit of snapping back at the press and there was all the politics: Bad enough he was 4-F; did he have to sing “Ol’ Man River” and break bread with Eleanor Roosevelt? Evans spent the better part of the forties covering Frank’s ass, cozying up to some columnists and scratching and clawing at others while his client carried on however he pleased, simply assuming that somebody else would sweep it up.

He rose to insane heights. In 1939, he was waiting tables at the Rustic Cabin for $15 a week; by the end of the war, he was a bigger star in more media than anyone in the world and had grossed an estimated $11 million. By sheer earnings standards, he was probably the biggest star ever, anywhere; it almost didn’t matter that he was an artistic genius with more pure vocal talent than virtually anyone who’d ever been recorded.

Still and all, he was a creature of the popular culture and, as such, subject to the public’s whimsies. As the forties closed, talk leaked into the press about ties to communism and mobsters, there were ugly spats with writers, photographers, waiters, carhops, fans. His once-promising film career had sputtered—The Kissing Bandit, anyone?—and, after Frank made a wisecrack about one of Louis B. Mayer’s mistresses, MGM gave him his release. On the radio, he was bumped down from Your Hit Parade to a fifteen-minute, B-level show; on TV, CBS just plain dumped him.

He had trouble with his voice—he opened his mouth once at the Copa and couldn’t make a sound come out—and he seemed, further, to have lost his aesthetic way, letting Columbia’s new A&R man, Mitch Miller, talk him into making horseshit records with arrangements scaled wrong for his voice and dog barks thrown in as comic relief. The pathetic fall seemed poetically complete in 1952 when he returned to the Paramount Theater in support of a film of his own (the forgettable Meet Danny Wilson) and couldn’t even fill the balcony, much less stop traffic in Times Square.

Frank had gone from “extra added attraction” to King of the Universe in a couple of years; then, in about the same time span, he couldn’t get a job—and not a few people in the business were glad of it. With his ambition, quick temper, and iconoclasm, he’d done a lot of pissing off in his decade on the scene. His reputation was poison: When Capitol Records president Alan Livingston told his staff that he’d signed Sinatra at terms very favorable to the company, they groaned as one.

Presaging all of this calamity, turning the bobby-soxers against him and making him look like some pathetic pussy-whipped Milquetoast, was his wanton affair with Ava Gardner. Frank had never been faithful to Nancy in even a loose sense of the word, but, like many showbiz wives, she seemed willing to put up with peccadilloes even with such hot numbers as Marilyn Maxwell and Lana Turner. But this thing with Ava was more passionate and public than any of his other dalliances; it might have begun as a meaningless Hollywood fling, but they carried on all over the country throughout 1949, and Frank’s cardboard marriage finally became untenable. In the spring of 1950, he left the pretty Italian girl and the three cute kids that were his P.R. chastity belt. George Evans, enervated and skinny to begin with, bald from defending him, up and died one night after arguing with a columnist about Frank and Ava; he was forty-eight, and his heart had given out.