Kitabı oxu: «The Woman Destroyed»

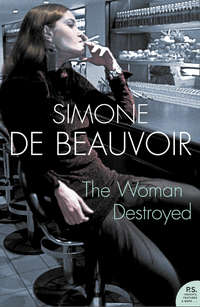

SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR

The Woman Destroyed

Translated by Patrick O’Brian

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

http://www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2006

Previously published in paperback by Flamingo 1994 (as a Flamingo Modern Classic) and 1984, and by Fontana 1971

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1969

First published in France by Editions Gallimard under the title La Femme Rompue 1967

Copyright © in the French edition, Editions Gallimard 1967

Copyright © in the English translation, William Collins Sons & Co Ltd,

London and Glasgow, and G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1969

PS Section copyright © Louise Tucker 2006

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © MAY 2018 ISBN 9780007405596

Version: 2018-05-16

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

The Age of Discretion

The Monologue

The Woman Destroyed

P.S. Ideas, Interviews & Features…

About the Author

‘The Art of Fiction’ 35, The Paris Review, 1965

Life at a Glance

Read On

Have You Read?

If You Loved this, You Might Like …

Find Out More

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

THE AGE OF DISCRETION

Has my watch stopped? No. But its hands do not seem to be going round. Don’t look at them. Think of something else—anything else: think of yesterday, a calm, ordinary, easy-flowing day, in spite of the nervous tension of waiting.

Tender awakening. André was in an odd, curled-up position in bed, with the bandage over his eyes and one hand pressed against the wall like a child’s, as though in the confusion and distress of sleep he had needed to reach out to test the firmness of the world. I sat on the edge of his bed; I put my hand on his shoulder.

‘Eight o’clock.’

I carried the breakfast-tray into the library: I took up a book that had arrived the day before—I had already half leafed through it. What a bore, all this going on about non-communication. If you really want to communicate you manage, somehow or other. Not with everybody, of course, but with two or three people. Sometimes I don’t tell André about my moods, sorrows, unimportant anxieties; and no doubt he has his little secrets too; but on the whole there is nothing we do not know about one another. I poured out the China tea, piping hot and very strong. We drank it as we looked through our post: the July sun came flooding into the room. How many times had we sat there opposite one another at that little table with piping hot, very strong cups of tea in front of us? And we should do so again tomorrow, and in a year’s time, and in ten years’ time … That moment possessed the sweet gentleness of a memory and the gaiety of a promise. Were we thirty, or were we sixty?

André’s hair had gone white when he was young: in earlier days that snowy hair, emphasizing the clear freshness of his complexion, looked particularly dashing. It looks dashing still. His skin has hardened and wrinkled—old leather—but the smile on his mouth and in his eyes has kept its brilliance. Whatever the photograph-album may say to the contrary, the pictures of the young André conform to his present-day face: my eyes attribute no age to him. A long life filled with laughter, tears, quarrels, embraces, confessions, silences, and sudden impulses of the heart: and yet sometimes it seems that time has not moved by at all. The future still stretches out to infinity.

He stood up. ‘I hope your work goes well,’ he said.

‘Yours too,’ I replied.

He made no answer. In this kind of research there are necessarily times when one makes no progress: he cannot accept that as readily as he used to do.

I opened the window. Paris, sweltering beneath the crushing summer heat, smelt of asphalt and impending storms. My eyes followed André. Maybe it is during those moments, as I watch him disappear, that he exists for me with the most overwhelming clarity: his tall shape grows smaller, each pace marking out the path of his return; it vanishes and the street seems to be empty; but in fact it is a field of energy that will lead him back to me as to his natural habitat: I find this certainty even more moving than his presence.

I paused on the balcony for a long while. From my sixth floor I see a great stretch of Paris, with pigeons flying over the slate-covered roofs, and those seeming flowerpots that are really chimneys. Red or yellow, the cranes—five, nine, ten: I can count ten of them—hold their iron arms against the sky: away to the right my gaze bumps against a great soaring wall with little holes in it—a new block: I can also see prism-like towers—recently-built tall buildings. Since when have cars been parked in the tree-lined part of the boulevard Edgar-Quinet? I find the newness of the landscape staringly obvious; yet I cannot remember having seen it look otherwise. I should like two photographs to set side by side, Before and After, so that I could be amazed by the differences. No: not really. The world brings itself into being before my eyes in an everlasting present: I grow used to its different aspects so quickly that it does not seem to me to change.

The card-indexes and blank paper on my desk urged me to work; but there were words dancing in my head that prevented me from concentrating. ‘Philippe will be here this evening.’ He had been away almost a month. I went into his room. Books and papers were still lying about—an old grey pull-over, a pair of violet pyjamas—in this room that I cannot make up my mind to change because I have not the time to spare, nor the money; and because I do not want to believe that Philippe has stopped belonging to me. I went back into the library, which was filled with the scent of a bunch of roses, as fresh and simple-minded as so many lettuces. I was astonished that I could ever have thought the flat forlorn and empty. There was nothing lacking. My eyes wandered with pleasure over the cushions scattered on the divans, some softly coloured, some vivid: the Polish dolls, the Slovak bandits and the Portuguese cocks were all in their places, as good as gold. ‘Philippe will be here …’ I was still at a loss for anything to do. Sadness can be wept away. But the impatience of delight—it is not so easy to get rid of that.

I made up my mind to go out and get a breath of the summer heat. A tall negro in an electric blue raincoat and a grey felt hat was listlessly sweeping the pavement: before, it used to be an earth-coloured Algerian. In the boulevard Edgar-Quinet I mingled with the crowd of women. As I almost never go out in the morning any more, the market had an exotic air for me (so many morning markets, beneath so many skies). The little old lady hobbled from one stall to another, her sparse hair carefully combed back, her hand grasping the handle of her empty basket. In earlier days I never used to worry about old people; I looked upon them as the dead whose legs still kept moving. Now I see them—men and women: only a little older than myself. I had noticed this old lady at the butcher’s one day when she asked for scraps for her cats. ‘For her cats!’ he said when she had gone. ‘She hasn’t got a cat. Such a stew she’s going to make for herself!’ The butcher found that amusing. Presently she will be picking up the leavings under the stalls before the tall negro sweeps everything into the gutter. Making ends meet on a hundred and eighty francs a month: there are more than a million in the same plight: three million more scarcely less wretched.

I bought some fruit, some flowers, and sauntered along. Retired: it sounds rather like rejected, tossed on to the scrap-heap. The word used to chill my heart. The great stretch of free time frightened me. I was mistaken. I do find the time a little too broad over the shoulders; but I manage. And how delightful to live with no imperatives, no kind of restraint! Yet still from time to time a bewilderment comes over me. I remember my first appointment, my first class, and the dead leaves that rustled under my feet that autumn in the country. In those days retirement seemed to me as unreal as death itself, for between me and that day there lay a stretch of time almost twice as long as that which I had so far lived. And now it is a year since it came. I have crossed other frontiers, but all of them less distinct. This one was as rigid as an iron curtain.

I came home; I sat at my desk. Without some work I should have found even that delightful morning insipid. When it was getting on for one o’clock I stopped so as to lay the table in the kitchen—just like my grandmother’s kitchen at Milly (I should like to see Milly again)—with its farmhouse table, its benches, its copper pots, the exposed beams: only there is a gas-stove instead of a range, and a refrigerator. (What year was it that refrigerators first came to France? I bought mine ten years ago, but they were already quite usual by then. When did they begin? Before the war? Just after? There’s another of those things I don’t remember any more.)

André came in late; he had told me he would. On leaving the laboratory he had attended a meeting on French nuclear weapons.

‘Did it go well?’ I asked.

‘We settled the wording of a new manifesto. But I have no illusions about it. It will have no more effect than the rest of them. The French don’t give a damn. About the deterrent, the atomic bomb in general—about anything. Sometimes I feel like getting the hell out of here—going to Cuba, to Mali. No, seriously, I do think about it. Out there it might be possible to make oneself useful.’

‘You couldn’t work any more.’

‘That would be no very great disaster.’

I put salad, ham, cheese and fruit on the table. ‘Are you as disheartened as all that? This is not the first time you people have been unable to make headway.’

‘No.’

‘Well, then?’

‘You don’t choose to understand.’

He often tells me that nowadays all the fresh ideas come from his colleagues and that he is too old to make new discoveries: I don’t believe him. ‘Oh, I can see what you are thinking,’ I said. ‘I don’t believe it.’

‘You’re mistaken. It is fifteen years since I had my last idea.’

Fifteen years. None of the sterile periods he has been through before have lasted that long. But having reached the point he has reached, no doubt he needs a break of this kind to come by fresh inspiration. I thought of Valéry’s lines

Chaque atome de silence Est la chance d’un fruit mûr.

Unlooked-for fruit will come from this slow gestation. The adventure in which I have shared so passionately is not over—this adventure with its doubt, failure, the dreariness of no progress, then a glimpse of light, a hope, a hypothesis confirmed; and then after weeks and months of anxious perseverance, the intoxication of success. I do not understand much about André’s work, but my obstinate confidence used to reinforce his. My confidence is still unshaken. Why can I no longer convey it to him? I will not believe that I am never again to see the feverish joy of discovery blazing in his eyes. I said, ‘There is nothing to prove that you will not get your second wind.’

‘No. At my age one has habits of mind that hamper inventiveness. And I grow more ignorant year by year.’

‘I will remind you of that ten years from now. Maybe you will make your greatest discovery at seventy.’

‘You and your optimism; I promise you I shan’t.’

‘You and your pessimism!’

We laughed. Yet there was nothing to laugh about. André’s defeatism has no valid basis: for once he is lacking in logical severity. To be sure, in his letters Freud did say that at a given age one no longer discovers anything new, and that it is terribly sad. But at that time he was much older than André. Nevertheless this extreme gloominess still saddens me just as much, although it is unjustified. And the reason why André gives way to it is that he is in a state of general crisis. It surprises me, but the truth of the matter is that he cannot bring himself to accept the fact that he is over sixty. For my own part I still find countless things amusing: he does not. Formerly he was interested in everything: now it is a tremendous business to drag him as far as a cinema or an exhibition, or to see friends.

‘What a pity it is that you no longer like walking,’ I said. ‘These days are so lovely! I was thinking just now how I should have liked to go back to Milly, and into the forest at Fontainebleau.’

‘You are an amazing woman,’ he said with a smile. ‘You know the whole of Europe, and yet what you want to see again is the outskirts of Paris!’

‘Why not? The church at Champeaux is no less beautiful because I have climbed the Acropolis.’

‘All right. As soon as the laboratory closes in four or five days’ time, I promise you a long run in the car.’

We should have time to go for more than one, since we are staying in Paris until the beginning of August. But would he want to? I said, ‘Tomorrow is Sunday. You’re not free?’

‘No, alas. As you know there’s this press-conference on apartheid in the evening. They’ve brought me a whole pile of papers I have not looked at yet.’

Spanish political prisoners; Portuguese detainees; persecuted Persians; Congolese, Angolan, Cameroonian rebels; Venezuelan, Peruvian and Colombian resistance fighters; he is always ready to help them as much as ever he can. Meetings, manifestoes, public gatherings, tracts, delegations—he jibs at nothing.

‘You do too much.’

What is there to do when the world has lost its savour? All that is left is the killing of time. I went through a wretched period myself, ten years ago. I was disgusted with my body; Philippe had grown up; and after the success of my book on Rousseau I felt completely hollow inside. Growing old filled me with distress. But then I began to work on Montesquieu, I got Phillipe through his agrégation * and managed to make him start on a thesis. I was given a lectureship at the Sorbonne and I found my teaching there even more interesting than my university-scholarship classes. I became resigned to my body. It seemed to me that I came to life again. And now, if André were not so very sharply aware of his age, I should easily forget my own altogether.

He went out again, and again I stayed a long while on the balcony. I watched an orange-red crane turning against the blue background of the sky. I watched a black insect that drew a broad, foaming, icy furrow across the heavens. The eternal youth of the world makes me feel breathless. Some things I loved have vanished. A great many others have been given to me. Yesterday evening I was going up the boulevard Raspail and the sky was crimson; it seemed to me that I was walking upon an unknown planet where the grass might be violet, the earth blue. It was trees hiding the red glare of a neon-light advertisement. When he was sixty André was astonished at being able to cross. Sweden in less than twenty-four hours, whereas in his youth the journey had taken a week. I have experienced wonders like that. Moscow in three and a half hours from Paris!

A cab took me to the Parc Montsouris, where I had an appointment with Martine. As I came into the gardens the smell of cut grass wrung my heart—the smell of the high Alpine pastures where I used to walk with André with a sack on my shoulders, a smell so moving because it was that of the meadows of childhood. Reflexions, echoes, reverberating back and back to infinity: I have discovered the pleasure of having a long past behind me. I have not the leisure to tell it over to myself, but often, quite unexpectedly, I catch sight of it, a background to the diaphanous present; a background that gives its colour and its light, just as rocks or sand show through the shifting brilliance of the sea. Once I used to cherish schemes and promises for the future; now my feelings and my joys are smoothed and softened with the shadowy velvet of time past.

‘Hallo!’

Martine was drinking lemon juice on the café terrace. Thick blade hair, blue eyes, a short dress with orange and yellow stripes and a hint of violet: a lovely young woman. Forty. When I was thirty I smiled to hear André’s father describe a forty-year-old as a ‘lovely young woman’; and here were the same words on my own lips, as I thought of Martine. Almost everybody seems to me to be young, now. She smiled at me. ‘You have brought me your book?’

‘Of course.’

She looked at what I had written in it. ‘Thank you,’ she said, with some emotion. She added, ‘I so long to read it. But one is so busy at the end of the school year. I shall have to wait for July 14.’

‘I should very much like to know what you think.’

I have great trust in her judgment: that is to say we are almost always in agreement. I should feel on a completely equal footing with her if she had not retained a little of that old pupil-teacher deference towards me, although she is a teacher herself, married and the mother of a family.

‘It is hard to teach literature nowadays. Without your books I really should not know how to set about it.’ Shyly she asked, ‘Are you pleased with this one?’

I smiled at her. ‘Frankly, yes.’

There was still a question in her eyes—one that she did not like to put into words. I made the first move. ‘You know what I wanted to do—to start off with a consideration of the critical works published since the war and then to go on to suggest a new method by which it is possible to make one’s way into a writer’s work, to see it in depth, more accurately than has ever been done before. I hope I have succeeded.’

It was more than a hope: it was a conviction. It filled my heart with sunlight. A lovely day: and I was enchanted with these trees, lawns, walks where I had so often wandered with friends and fellow-students. Some are dead, or life has separated us. Happily—unlike André, who no longer sees anyone—I have made friends with some of my pupils and younger colleagues: I like them better than women of my own age. Their curiosity spurs mine into life: they draw me into their future, on the far side of my own grave.

Martine stroked the book with her open hand. ‘Still, I shall dip into it this very evening. Has anyone read it?’

‘Only André. But literature does not mean a very great deal to him.’

Nothing means a very great deal to him any more. And he is as much of a defeatist for me as he is for himself. He does not tell me so, but deep down he is quite sure that from now on I shall do nothing that will add to my reputation. This does not worry me, because I know he is wrong. I have just written my best book and the second volume will go even farther.

‘Your son?’

‘I sent him proofs. He will be telling me about it—he comes back this evening.’

We talked about Philippe, about his thesis, about writing. Just as I do she loves words end people who know how to use them. Only she is allowing herself to be eaten alive by her profession and her home. She drove me back in her little Austin.

‘Will you come back to Paris soon?’

‘I don’t think so. I am going straight on from Nancy into the Yonne, to rest.’

‘Will you do a little work during the holidays?’

‘I should like to. But I’m always short of time. I don’t possess your energy.’

It is not a matter of energy, I said to myself as I left her: I just could not live without writing. Why? And why was I so desperately eager to make an intellectual out of Philippe when André would have let him follow other paths? When I was a child, when I was an adolescent, books saved me from despair: that convinced me that culture was the highest of values, and it is impossible for me to examine this conviction with an objective eye.

In the kitchen Marie-Jeanne was busy getting the dinner ready: we were to have Philippe’s favourite dishes. I saw that everything was going well. I read the papers and I did a difficult crossword-puzzle that took me three quarters of an hour: from time to time it is fun to concentrate for a long while upon a set of squares where the words are potentially there although they cannot be seen: I use ray brain as a photographic developer to make them appear—I have the impression of drawing them up from their hiding-places in the depth of the paper.

When the last square was filled I chose the prettiest dress in my wardrobe—pink and grey foulard. When I was fifty my clothes always seemed to me either too cheerful or too dreary: now I know what I am allowed and what I am not, and I dress without worrying. Without pleasure either. That very close, almost affectionate relationship I once had with my clothes has vanished. Nevertheless, I did look at my figure with some gratification. It was Philippe who said to me one day, ‘Why, look, you’re getting plump.’ (He scarcely seems to have noticed that I have grown slim again.) I went on a diet. I bought scales. Earlier on it never occurred to me that I should ever worry about my weight. Yet here I am! The less I identify myself with my body the more I feel myself required to take care of it. It relies on me, and I looked after it with bored conscientiousness, as I might look after a somewhat reduced, somewhat wanting old friend who needed my help.

André brought a bottle of Mumm and I put it to cool; we talked for a while and then he telephoned his mother. He often telephones her. She is sound in wind and limb and she is still a furious militant in the ranks of the Communist Party; but she is eighty-four and she lives alone in her house at Villeneuve-lès-Avignon. He is rather anxious about her. He laughed on the telephone; I heard him cry out and protest; but he was soon cut short—Manette is very talkative whenever she has the chance.

‘What did she say?’

‘she is more and more certain that one day or another fifty million Chinese will cross the Russian frontier. Or else that they will drop a bomb anywhere, just anywhere, for the pleasure of setting off a world war. She accuses me of taking their side: there’s no persuading her I don’t.’

‘Is she well? She’s not bored?’

‘she will be delighted to see us; but as for bring bored, she doesn’t know the meaning of the word.’

She had been a school-teacher with three children, and, for her, retirement is a delight that she has not yet come to the end of. We talked about her and about the Chinese, of whom we, like everybody else, know so very little. André opened a magazine. And there I was, looking at my watch, whose hands did not seem to be going round.

All at once he was there: every time it surprises me to see his face, with the dissimilar features of my mother and André blending smoothly in it. He hugged me very tight, saying cheerful things, and I leant there with the softness of his flannel jacket against my cheek. I released myself so as to kiss Irène: she smiled at me with so frosty a smile that I was astonished to feel a soft, warm cheek beneath my lips. Irène. I always forget her; and she is always there. Blonde; grey-blue eyes; weak mouth; sharp chin; and something both vague and obstinate about her too-wide forehead. Quickly I wiped her out. I was alone with Philippe as I used to be in the days when I woke him up every morning with a touch on his forehead.

‘Not even a drop of whisky?’ asked André.

‘No, thanks. I’ll have some fruit-juice.’

How sensible she is! She dresses with a sensible stylishness; sensibly stylish hair-do—smooth, with a fringe hiding her big forehead. Artless make-up: severe little suit. When I happen to run through a woman’s magazine I often say to myself, ‘Why, here’s Irène!’ It often happens too that when I see her I scarcely recognize her. ‘She’s pretty,’ asserts André. There are days when I agree—a delicacy of ear and nostril: a pearly softness of skin emphasized by the dark blue of her lashes. But if she moves her head a little her face slips, and all you see is that mouth, that chin. Iréne. Why? Why has Philippe always gone for women of that kind—smooth, stand-offish, pretentious? To prove to himself that he could attract them, no doubt. He was not fond of them. I used to think that if he fell in love … I used to think he would not fall in love; and one evening he said to me, ‘I have great news for you,’ with the somewhat over-excited air of a birthday-child who has been playing too much, laughing too much, shouting too much. There was that crash like a gong in my bosom, the blood mounting to my cheeks, all my strength concentrated on stopping the trembling of my lips. A winter evening, with the curtains drawn and the lamplight on the rainbow of cushions, and this suddenly-opened gulf, this chasm of absence. ‘You will like her: she is a woman who has a job.’ At long intervals she works as a script-girl. I know these with-it young married women. They have some vague kind of a job, they claim to use their minds, to go in for sport, dress well, run their houses faultlessly, bring up their children perfectly, carry on a social life—in short, succeed on every level. And they don’t really care deeply about anything at all. They make my blood run cold.

Philippe and Irène had left for Sardinia the day the university closed, at the beginning of June. While we were having dinner at that table where I had so often obliged Philippe to eat (come, finish up your soup: take a little more beef: get something down before going off for your lecture), we talked about their journey—a handsome wedding-present from Irène’s parents, who can afford that sort of thing. She was silent most of the time, like an intelligent woman who knows how to wait for the right moment to produce an acute and rather surprising remark: from time to time she did drop a little observation, surprising—or at least surprising to me—by its stupidity or its utter ordinariness.

We went back to the library. Philippe glanced at my desk. ‘Did the work go well?’

‘Pretty well. You didn’t have time to read my proofs?’

‘No; can you imagine it? I’m very sorry.’

‘You’ll read the book. I have a copy for you.’ His carelessness saddened me a little, but I showed nothing. I said, ‘And what about you? Are you going to get back to serious work on your thesis again now?’ He did not answer. He exchanged an odd kind of look with Irène. ‘What’s the matter? Are you going to set off on your travels again?’

‘No.’ Silence again and then he said rather crossly, ‘Oh, you’ll be vexed; you’ll blame me; but during this month I have come to a decision. It is altogether too much, teaching and working on a thesis at the same time. But unless I do a thesis there is no worthwhile future for me in the university. I am going to leave.’

‘What on earth are you talking about?’

‘I’m going to leave the university. I’m still young enough to take up something else.’

‘But it’s just not possible. Now that you have got this far you cannot drop it all,’ I said indignantly.

‘Listen. Once upon a time being a don was a splendid career. These days I am not the only one who finds it impossible to look after my students and do any work of my own: there are too many of them.’

That’s quite true,’ said Andrè. ‘Thirty students is one student multiplied by thirty. Fifty is a mob. But surely we can find some way that will give you more time to yourself and let you finish your thesis.’

‘No,’ said Irène, decisively. ‘Teaching and research—they really are too badly paid. I have a cousin who is a chemist. At the National Research Centre he was earning eight hundred francs a month. He has gone into a dye factory—he’s pulling down three thousand.’

‘It’s not only a question of money,’ said Philippe.

‘Of course not. Being in the swim counts too.’

In little guarded, restrained phrases she let us see what she thought of us. Oh, she did it tactfully—with the tact you can hear rumbling half a mile away. ‘Above all I don’t want to hurt you—don’t hold it against me, for that would be unfair—but still there are some things I have to say to you and if I were not holding myself in I’d say a great deal more.’ Andrè is a great scientist of course and for a woman I haven’t done badly at all. But we live cut off from the world, in laboratories and libraries. The new generation of intellectuals wants to be in immediate contact with society. With his vitality and drive, Philippe is not made for our kind of life; there are other careers in which he would show his abilities far better. ‘And then of course a thesis is totally old hat,’ she ended.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.