Kitab fayl olaraq yüklənə bilməz, yalnız mobil tətbiq və ya onlayn olaraq veb saytımızda oxuna bilər.

Kitabı oxu: «Girl With a Pearl Earring»

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1999

Copyright © Tracy Chevalier 1999

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

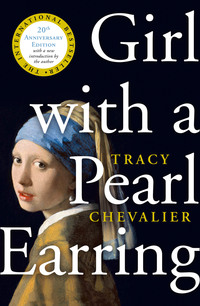

Cover image Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665-6 (oil on canvas), Vermeer, Jan (Johannes) (1632-75) / Mauritshuis, The Hague, The Netherlands / Bridgeman Images

Tracy Chevalier asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007232161

Ebook Edition © December 2018 ISBN: 9780007324361

Version: 2018-12-10

Praise for Girl with a Pearl Earring:

‘Timeless, delicate and as exquisitely measured as one of Vermeer’s paintings, this novel entered my life when I was 16, and plunged me, probably forever, into the world of Golden Age Holland. Tense yet perfectly paced and filled with the beauty of life’s colours, Tracy Chevalier’s story of the personal costs behind art’s public genius is a masterpiece in its own right. I will hold this novel close for the rest of my life’

JESSIE BURTON

‘A portrait of radiance … Tracy Chevalier brings the real artist Vermeer and a fictional muse to life in a jewel of a novel’

TIME

‘Chevalier doesn’t put a foot wrong in this triumphant work … It is a beautifully written tale that mirrors the elegance of the painting that inspired it’

WALL STREET JOURNAL

‘It has a slow, magical current of its own that picks you up and carries you stealthily along … a beautiful story, lovingly told by a very talented writer’

DAILY MAIL

‘Chevalier’s writing skill and her knowledge of 17th-century Delft are such that she creates a world reminiscent of a Vermeer interior: suspended in a particular moment, it transcends its time and place’

NEW YORKER

‘This is a wonderful novel, mysterious, steeped in atmosphere. It is deeply revealing about the process of painting … a truly magical experience’

GUARDIAN

‘This is a novel which deserves, and I am sure will win, a prize – or two’

THE TIMES

‘Life in 17th-century Delft is evoked with a sharp eye for historical detail and the descriptions of Vermeer at work are superbly drawn. A sensuous and vividly crafted work of fiction from a highly-talented young novelist’

MAIL ON SUNDAY

Dedication

For my father

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Introduction

Reflections on Girl with a Pearl Earring

1664

1665

1666

1676

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Tracy Chevalier

About the Publisher

Introduction

Time is so elastic that twenty years can feel like a lifetime or a week. To me it seems only a year or two since Girl with a Pearl Earring was quietly published in the dog-days of August 1999, with little fanfare and a couple of respectable reviews.

Five million copies later, forty-three languages later (not counting Persian: illegally published, then banned by the Iranian government, recently unbanned – but still illegal!), a film with Scarlett Johansson and Colin Firth later, this book is still running. It has legs, as they say. And I am still a little stunned by its success.

My relationship with Vermeer’s painting Girl with a Pearl Earring extends back far more than twenty years, however. I first discovered it existed in Autumn 1981 when I visited my sister in Boston. Walking into her apartment, I made a beeline for the poster of an unfamiliar painting that hung on her wall. The light, the colours, the girl’s piercing gaze: I was smitten. So much so that the next day I bought a poster of it for myself. It has accompanied me everywhere I’ve lived since. I even took it to London and back on a semester abroad during my university years. That same poster – now tattered and faded – still hangs in my study, and I look at it every day. Despite my love affair with the Girl, though, I only saw the painting in the flesh for the first time at a seminal Vermeer retrospective at the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague in Spring 1996.

I have always been mesmerized by its beauty. The bright blue and yellow of the Girl’s antique headdress, the way light and shadow sculpt her face, the liquid pools of her eyes, the perfectly placed dab of white pearl in the dark shadow of her neck: these details are all not so much about the beauty of this particular girl herself, but choices Vermeer made in how to portray her. In fact, this is not a portrait of a specific person, but a tronie, a Dutch term for an idealized head of a ‘type’ of person, in this case a young woman. It is meant to be a universal image.

And yet: that gaze is specific. She is looking at us as if she knows us.

That last sentence contains a mistake that took me sixteen years to correct. One morning in November 1997 I was lying in bed in my London flat, looking at the poster, sixteen years after first discovering the Girl in Boston, and thought, ‘I wonder what Vermeer did to make her look at him like that.’ It was like a switch flipped. I had always thought she was looking at me, at us. But of course she wasn’t ever looking at us – she was looking at Vermeer when he painted her. That unreadable gaze – that yearning, guarded look – is at him.

Suddenly the painting became not about a specific girl, or even an idealized girl, but about a relationship. And what was that relationship? We don’t know. No one knows who the model was, and we know little about Vermeer either.

Right away I knew I was onto something. It’s rare to pinpoint specific moments in our lives that are true forks in the road, but that morning was one of them for me. A switch kind of flipped in my writing life too, and everything changed. Within three days I had made up the story of Griet, the servant who cleans Vermeer’s studio and catches his eye.

I researched and wrote Girl with a Pearl Earring in a dream-like bubble – quickly over nine months (I was pregnant, with a built-in biological deadline), as an unknown writer with no expectations from readers or publishers or myself. When I wrote the book I tried hard to be respectful of Vermeer, of the process, of the painting. I left a lot of space – literal (it’s short) and figurative – for the reader to consider and form her own opinions. In the worst-case scenario, people read Girl with a Pearl Earring and turn to the cover to study the painting. In the best case, afterwards they study other paintings more carefully too. My favourite contact with readers is when they tell me they look at art differently now.

Why has the book been so popular that we’re celebrating its 20th anniversary? Partly it’s the strength of the painting. But the novel also has a rare quality that I am not sure I will ever be able to replicate in another book. The style reflects and supports the subject. When I was first working on it I thought: You’re writing about Vermeer, so write it the way he paints – spare, focussed, stripped down to the essentials. Two clichés absolutely worked for me: Less Is More, and Form Follows Function. Many novels tell stories well, or create a unique style, but few successfully combine the two so that they support each other and become more than the sum of their parts.

Since that Mauritshuis show in 1996 and – perhaps – since the book’s success, Vermeer has become a Big Deal. Probably he would have anyway, and I am simply the luckiest writer ever to have been in the right place at the right time and able to ride the wave of his popularity. Even given that there are only thirty-six Vermeer paintings in existence, he is now one of the most exhibited Old Masters. Over the last twenty years I have seen Vermeer shows in London, New York, Madrid, Rome, Cambridge, Dublin. Most only displayed two or three Vermeers, and bulked out the offering with work by his contemporaries, with themes focussing on his hometown of Delft, or women, or genre paintings, or music – whatever link they could make that justifies showing the Vermeers.

Inevitably, to me at least, Vermeer’s paintings always leapt out from the others. His work has an ethereal quality that is hard to pinpoint. His colours are intense, his focus tight, his subjects seem to be in worlds of their own that we only get a peek at without being invited in. Viewers spend a long time in front of his work, much longer than with others. They are trying to figure out the magic. But that’s the thing about magic – it only works when you don’t know the trick.

If anything, the painting itself is even more popular than Vermeer himself. The image of the Girl is everywhere, on umbrellas, suitcases, jigsaw puzzles, bookmarks, water bottles. There is a Miffy doll dressed as the Girl, and a rubber duck of her that I float in my bath. Banksy has painted her on a Bristol wall with an existing security alarm in place of her earring. A friend’s daughter dressed up as her for Hallowe’en. My cousin Pierre had a boutique vineyard for a while in California and named his best bottle ‘One Pearl’, with the painting on the label. I have on occasion worn socks where the Girl peeks out from my ankles.

Social media is awash with images of her. There are over 25,000 Instagram posts with the hashtag #girlwithapearlearring featuring drawings and paintings copying the painting, embroidery of the image, cats and dogs inserted in place of her face, and lots and lots of people dressed up like her... Back before social media became the place to communicate, readers used to write to me sending photos of themselves or their daughter or their friend, dressed up as the Girl. Doesn’t my daughter look just like her? they said. No one does, however. Despite the universality of her appearance – her hair and eye colour unknown, her face turned so we can’t see the shape of her nose – the Girl is decidedly herself.

Do I feel guilty about this overexposure? Sometimes. The novel may well have played a part in that. But no matter how dispiriting it is to see an image of Girl with a Pearl Earring on an ashtray, somehow the painting manages to rise above such exposure and maintain its fundamental mystery. What is the Girl feeling as she looks at the painter? I have written a novel about that look, and talked about it for twenty years, and I still don’t know. As long as the mystery remains – and it always will, I think – we will be enchanted by the painting and everything associated with it.

Tracy Chevalier

February 2019

Reflections on Girl with a Pearl Earring

by Rose Tremain

I’ve been trying to analyse what makes this novel so successful – a veritable work of art.

I feel that two things are key: the pace and the form.

Much is made, in the book, of the fact that Vermeer painted slowly – too slowly for the whims of his family, who waited so impatiently for works to be finished and to be sold for good money. It seems to me that Tracy has made a beautiful virtue out of this slowness in the shaping of her novel. Things unfold in a calm, unhurried and uncluttered way. The narrative has almost a shy coyness about itself, willing to give us only so much at any one time to lure the reader deeper and deeper into the story. It moves at Vermeer’s pace. But, just as we are confident that the artist is embarked on works of great beauty and stillness, so, here, we see the author quietly bringing to life a delicate human drama.

How Tracy controls the form is complex. It relates, once again to Vermeer himself and the gentle way in which the innocent maid, Griet, begins to understand his technique, which is unhurried and arduous. He moves people, objects and furniture around until he has found the combination that feels right to him. And Tracy does the same, giving us ever-changing alignments of the circumstances and the people who are going to shape Griet’s destiny. When Vermeer begins to paint, he does surprising things, laying on dull backgrounds before beginning to sketch in the figures. He explains to Griet that the colour white is almost never ‘pure’, but brought to purity, and brought to its crucial role in a painting (eventually the earring itself) by the presence of other tones within it.

And this is how Tracy shapes her narrative – by small, unexpected increments, often defined by colour (the red of the butcher’s blood under Pieter’s nails, the cloudy white of the laundry, the Delft blue of Griet’s father’s tiles, the flaming tones of Cornelia’s hair) laying them in sparingly and – most crucial of all – never anticipating for us too neatly what role they are going to play.

Tracy always researches her books very thoroughly. To write about quilt-making she makes quilts. To write about fossils, she gathers and studies them, thus giving great authenticity to the work. But in Girl with a Pearl Earring we experience a lot more than a feeling of a writer doing meticulous homework; we are led deep inside the strange, closed world of the artist and the innocent girl who, for a brief moment, moved him to a love he could only express through a picture. We are as captive to that world as Griet is captive to her master. This is one of those rare novels where all the decisions made by the author appear inevitable and right. And millions of readers agreed. They were perfectly at home in this book. They felt they were part of a timeless painting.

RT. 2018

My mother did not tell me they were coming. Afterwards she said she did not want me to appear nervous. I was surprised, for I thought she knew me well. Strangers would think I was calm. I did not cry as a baby. Only my mother would note the tightness along my jaw, the widening of my already wide eyes.

I was chopping vegetables in the kitchen when I heard voices outside our front door – a woman’s, bright as polished brass, and a man’s, low and dark like the wood of the table I was working on. They were the kind of voices we heard rarely in our house. I could hear rich carpets in their voices, books and pearls and fur.

I was glad that earlier I had scrubbed the front step so hard.

My mother’s voice – a cooking pot, a flagon – approached from the front room. They were coming to the kitchen. I pushed the leeks I had been chopping into place, then set the knife on the table, wiped my hands on my apron, and pressed my lips together to smooth them.

My mother appeared in the doorway, her eyes two warnings. Behind her the woman had to duck her head because she was so tall, taller than the man following her.

All of our family, even my father and brother, were small.

The woman looked as if she had been blown about by the wind, although it was a calm day. Her cap was askew so that tiny blonde curls escaped and hung about her forehead like bees which she swatted at impatiently several times. Her collar needed straightening and was not as crisp as it could be. She pushed her grey mantle back from her shoulders, and I saw then that under her dark blue dress a baby was growing. It would arrive by the year’s end, or before.

The woman’s face was like an oval serving plate, flashing at times, dull at others. Her eyes were two light brown buttons, a colour I had rarely seen coupled with blond hair. She made a show of watching me hard, but could not fix her attention on me, her eyes darting about the room.

‘This is the girl, then,’ she said abruptly.

‘This is my daughter, Griet,’ my mother replied. I nodded respectfully to the man and woman.

‘Well. She’s not very big. Is she strong enough?’ As the woman turned to look at the man, a fold of her mantle caught the handle of the knife I had been using, knocking it off the table so that it spun across the floor.

The woman cried out.

‘Catharina,’ the man said calmly. He spoke her name as if he held cinnamon in his mouth. The woman stopped, making an effort to quiet herself.

I stepped over and picked up the knife, polishing the blade on my apron before placing it back on the table. The knife had brushed against the vegetables. I set a piece of carrot back in its place.

The man was watching me, his eyes grey like the sea. He had a long, angular face, and his expression was steady, in contrast to his wife’s, which flickered like a candle. He had no beard or moustache, and I was glad, for it gave him a clean appearance. He wore a black cloak over his shoulders, a white shirt, and a fine lace collar. His hat pressed into hair the red of brick washed by rain.

‘What have you been doing here, Griet?’ he asked.

I was surprised by the question but knew enough to hide it. ‘Chopping vegetables, sir. For the soup.’

I always laid vegetables out in a circle, each with its own section like a slice of pie. There were five slices: red cabbage, onions, leeks, carrots and turnips. I had used a knife edge to shape each slice, and placed a carrot disc in the centre.

The man tapped his finger on the table. ‘Are they laid out in the order in which they will go into the soup?’ he suggested, studying the circle.

‘No, sir.’ I hesitated. I could not say why I had laid out the vegetables as I did. I simply set them as I felt they should be, but I was too frightened to say so to a gentleman.

‘I see you have separated the whites,’ he said, indicating the turnips and onions. ‘And then the orange and the purple, they do not sit together. Why is that?’ He picked up a shred of cabbage and a piece of carrot and shook them like dice in his hand.

I looked at my mother, who nodded slightly.

‘The colours fight when they are side by side, sir.’

He arched his eyebrows, as if he had not expected such a response. ‘And do you spend much time setting out the vegetables before you make the soup?’

‘Oh no, sir,’ I replied, confused. I did not want him to think I was idle.

From the corner of my eye I saw a movement. My sister, Agnes, was peering round the doorpost and had shaken her head at my response. I did not often lie. I looked down.

The man turned his head slightly and Agnes disappeared. He dropped the pieces of carrot and cabbage into their slices. The cabbage shred fell partly into the onions. I wanted to reach over and tease it into place. I did not, but he knew that I wanted to. He was testing me.

‘That’s enough prattle,’ the woman declared. Though she was annoyed by his attention to me, it was me she frowned at. ‘Tomorrow, then?’ She looked at the man before sweeping out of the room, my mother behind her. The man glanced once more at what was to be the soup, then nodded at me and followed the women.

When my mother returned I was sitting by the vegetable wheel. I waited for her to speak. She was hunching her shoulders as if against a winter chill, though it was summer and the kitchen was hot.

‘You are to start tomorrow as their maid. If you do well, you will be paid eight stuivers a day. You will live with them.’

I pressed my lips together.

‘Don’t look at me like that, Griet,’ my mother said. ‘We have to, now your father has lost his trade.’

‘Where do they live?’

‘On the Oude Langendijck, where it intersects with the Molenpoort.’

‘Papists’ Corner? They’re Catholic?’

‘You can come home Sundays. They have agreed to that.’ My mother cupped her hands around the turnips, scooped them up along with some of the cabbage and onions and dropped them into the pot of water waiting on the fire. The pie slices I had made so carefully were ruined.

I climbed the stairs to see my father. He was sitting at the front of the attic by the window, where the light touched his face. It was the closest he came now to seeing.

Father had been a tile painter, his fingers still stained blue from painting cupids, maids, soldiers, ships, children, fish, flowers, animals on to white tiles, glazing them, firing them, selling them. One day the kiln exploded, taking his eyes and his trade. He was the lucky one – two other men died.

I sat next to him and held his hand.

‘I heard,’ he said before I could speak. ‘I heard everything.’ His hearing had taken the strength from his missing eyes.

I could not think of anything to say that would not sound reproachful.

‘I’m sorry, Griet. I would like to have done better for you.’ The place where his eyes had been, where the doctor had sewn shut the skin, looked sorrowful. ‘But he is a good gentleman, and fair. He will treat you well.’ He said nothing about the woman.

‘How can you be sure of this, Father? Do you know him?’

‘Don’t you know who he is?’

‘No.’

‘Do you remember the painting we saw in the Town Hall a few years ago, which van Ruijven was displaying after he bought it? It was a view of Delft, from the Rotterdam and Schiedam Gates. With the sky that took up so much of the painting, and the sunlight on some of the buildings.’

‘And the paint had sand in it to make the brickwork and the roofs look rough,’ I added. ‘And there were long shadows in the water, and tiny people on the shore nearest us.’

‘That’s the one.’ Father’s sockets widened as if he still had eyes and was looking at the painting again.

I remembered it well, remembered thinking that I had stood at that very spot many times and never seen Delft the way the painter had.

‘That man was van Ruijven?’

‘The patron?’ Father chuckled. ‘No, no, child, not him. That was the painter. Vermeer. That was Johannes Vermeer and his wife. You’re to clean his studio.’

To the few things I was taking with me my mother added another cap, collar and apron so that each day I could wash one and wear the other, and would always look clean. She also gave me an ornamental tortoiseshell comb, shaped like a shell, that had been my grandmother’s and was too fine for a maid to wear, and a prayer book I could read when I needed to escape the Catholicism around me.

As we gathered my things she explained why I was to work for the Vermeers. ‘You know that your new master is headman of the Guild of St Luke, and was when your father had his accident last year?’

I nodded, still shocked that I was to work for such an artist.

‘The Guild looks after its own, as best it can. Remember the box your father gave money to every week for years? That money goes to masters in need, as we are now. But it goes only so far, you see, especially now with Frans in his apprenticeship and no money coming in. We have no choice. We won’t take public charity, not if we can manage without. Then your father heard that your new master was looking for a maid who could clean his studio without moving anything, and he put forward your name, thinking that as headman, and knowing our circumstances, Vermeer would be likely to try to help.’

I sifted through what she had said. ‘How do you clean a room without moving anything?’

‘Of course you must move things, but you must find a way to put them back exactly so it looks as if nothing has been disturbed. As you do for your father now that he cannot see.’

After my father’s accident we had learned to place things where he always knew to find them. It was one thing to do this for a blind man, though. Quite another for a man with a painter’s eyes.

Agnes said nothing to me after the visit. When I got into bed next to her that night she remained silent, though she did not turn her back to me. She lay gazing at the ceiling. Once I had blown out the candle it was so dark I could see nothing. I turned towards her.

‘You know I don’t want to leave. I have to.’

Silence.

‘We need the money. We have nothing now that Father can’t work.’

‘Eight stuivers a day isn’t such a lot of money.’ Agnes had a hoarse voice, as if her throat were covered with cobwebs.

‘It will keep the family in bread. And a bit of cheese. That’s not so little.’

‘I’ll be all alone. You’re leaving me all alone. First Frans, then you.’

Of all of us Agnes had been the most upset when Frans left the previous year. He and she had always fought like cats but she sulked for days once he was gone. At ten she was the youngest of us three children, and had never before known a time when Frans and I were not there.

‘Mother and Father will still be here. And I’ll visit on Sundays. Besides, it was no surprise when Frans went.’ We had known for years that our brother would start his apprenticeship when he turned thirteen. Our father had saved hard to pay the apprentice fee, and talked endlessly of how Frans would learn another aspect of the trade, then come back and they would set up a tile factory together.

Now our father sat by the window and never spoke of the future.

After the accident Frans had come home for two days. He had not visited since. The last time I saw him I had gone to the factory across town where he was apprenticed. He looked exhausted and had burns up and down his arms from pulling tiles from the kiln. He told me he worked from dawn until so late that at times he was too tired even to eat. ‘Father never told me it would be this bad,’ he muttered resentfully. ‘He always said his apprenticeship was the making of him.’

‘Perhaps it was,’ I replied. ‘It made him what he is now.’

When I was ready to leave the next morning my father shuffled out to the front step, feeling his way along the wall. I hugged my mother and Agnes. ‘Sunday will come in no time,’ my mother said.

My father handed me something wrapped in a handkerchief. ‘To remind you of home,’ he said. ‘Of us.’

It was my favourite tile of his. Most of his tiles we had at home were faulty in some way – chipped or cut crookedly, or the picture was blurred because the kiln had been too hot. This one, though, my father kept specially for us. It was a simple picture of two small figures, a boy and an older girl. They were not playing as children usually did in tiles. They were simply walking along, and were like Frans and me whenever we walked together – clearly our father had thought of us as he painted it. The boy was a little ahead of the girl but had turned back to say something. His face was mischievous, his hair messy. The girl wore her cap as I wore mine, not as most other girls did, with the ends tied under their chins or behind their necks. I favoured a white cap that folded in a wide brim around my face, covering my hair completely and hanging down in points on each side of my face so that from the side my expression was hidden. I kept the cap stiff by boiling it with potato peelings.

I walked away from our house, carrying my things tied up in an apron. It was still early – our neighbours were throwing buckets of water on to their steps and the street in front of their houses, and scrubbing them clean. Agnes would do that now, as well as many of my other tasks. She would have less time to play in the street and along the canals. Her life was changing too.

People nodded at me and watched curiously as I passed. No one asked where I was going or called out kind words. They did not need to – they knew what happened to families when a man lost his trade. It would be something to discuss later – young Griet become a maid, her father brought the family low. They would not gloat, however. The same thing could easily happen to them.

I had walked along that street all my life, but had never been so aware that my back was to my home. When I reached the end and turned out of sight of my family, though, it became a little easier to walk steadily and look around me. The morning was still cool, the sky a flat grey-white pulled close over Delft like a sheet, the summer sun not yet high enough to burn it away. The canal I walked along was a mirror of white light tinged with green. As the sun grew brighter the canal would darken to the colour of moss.

Frans, Agnes and I used to sit beside that canal and throw things in – pebbles, sticks, once a broken tile – and imagine what they might touch on the bottom – not fish, but creatures from our imagination, with many eyes, scales, hands and fins. Frans thought up the most interesting monsters. Agnes was the most frightened. I always stopped the game, too inclined to see things as they were to be able to think up things that were not.

There were a few boats on the canal, moving towards Market Square. It was not market day, however, when the canal was so full you couldn’t see the water. One boat was carrying river fish for the stalls at Jeronymous Bridge. Another sat low on the water, loaded with bricks. The man poling the boat called out a greeting to me. I merely nodded and lowered my head so that the edge of my cap hid my face.

Pulsuz fraqment bitdi.